The Best-Kept Secret of a Phoenix Neighborhood Is This Delicious Date

Black Sphinxes grow almost exclusively in Mountgrove backyards.

Palm trees aren’t native to Arizona, but they grow in Phoenix, and in a neighborhood called Mountgrove, regal palms soar like nowhere else in the city. Thick-trunked, lavish silvery-green fronds floating in the desert breeze, they lean skyward above sleepy roads, green yards, and rooftops in vaguely military formation. In all, some 300 palms stand. They are date palms, and not just any date palm. This small suburban stretch is the nearly exclusive home of the Black Sphinx, a world-class date found only in Phoenix and grown largely by residents, many surprised to learn their yards contain a hidden gem of Arizona agriculture.

“It’s one of those very soft dates that has just a wonderful flavor,” says Jim Montgomery, a date enthusiast who keeps palms and sells fruit just east of the city, including the Black Sphinx, his most popular varietal.

The impressive Phoenix grid of 50-foot palms pre-dates the homes; they are a legacy of when the U.S. government imported dates from the Middle East and North Africa in massive numbers, in hopes of making dates a pillar of a new regional economy. The fruit had first arrived in North American when Jesuits planted them at missions in the 1600s and 1700s. But it was in the 1880s, when Phoenix was just a young cattle and citrus town along the Salt and Gila Rivers, that the U.S. Department of Agriculture started to go all in on dates.

In Arizona, date groves rooted in Yuma, Dateland, and in and around Phoenix. The USDA was focused on farms, but the palms also helped turn Phoenix into a vacation spot. Jagged mountains! Eternal sunshine! Exotic palms! Entrepreneurs lured black-and-white-Hollywood-era tourists to date ranches across the Valley of the Sun. “Visitors would come out,” says Bill Benson, who moved to the Phoenix area in 1948 and owned a date grove east of the city from 1960 to 1972. “This was a strange fruit people had only heard about in the Bible … People all over the country were spending winter in Arizona.”

Within this milieu, a lucky discovery led to the brief flight of the Black Sphinx—a date new to the world. Origin stories vary. So do the protagonist and year. What they share, though, is that a date enthusiast walking in Phoenix noticed a curious offshoot sprouting from a palm—a growth from the trunk that, cut, might be replanted and grown into a full palm. This offshoot, believed to be born from the Halawi date, proved to be a new variety.

“Black” was its ripe fruit. “Sphinx” added enigma and allure. “As a sort of marketing tool, they wanted to give it an exotic-sounding name, to conjure up images of faraway lands,” says Scott Frische, a hobbyist palm grower and keeper of local date lore. Over time, some 12 acres of Black Sphinx offshoots were planted in Arcadia, where Mountgrove is today. Owned by Frank Brophy, this date farm, renamed Sphinx Date Ranch, soon became the Black Sphinx epicenter.

Today, the Black Sphinx remains a coveted date among locals, one whose annual September availability sparks a clandestine fury of texting, emailing, and whisper-networking about where to buy. (The Scottsdale shop Sphinx Date Co. is a reliable source that sends an email blast at first availability.) In Metro Phoenix, when Black Sphinx ripen, more broadly renowned varieties such as medjool and deglet noor are vanquished from larders and imaginations until the dark trickle of Sphinx stops. “Phoenicians think the Black Sphinx is the best date in the world,” says Frische, a local since the early 1960s.

And Phoenix residents have well-informed opinions, because date culture has flourished and then persisted on the metro area’s margins for generations. “Even a novice knows there is no comparison between Arizona and California dates,” reads a 1954 story in the magazine Arizona Days and Ways. “The former are bigger, sweeter, and more luscious.”

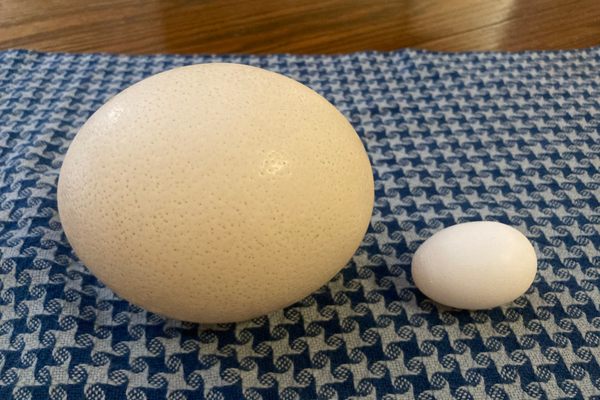

Unlike Black Sphinx, medjool dates are common in U.S. grocery stores because they ship well and pack sugar. Medjools have a syrupy, candy-like sweetness. Black Sphinx, on the other hand, carry a more muted sweetness, which leaves space for smaller notes—a faint nuttiness, a sugar eerily like caramel, a very dark fruit flash. A few of the more creative local chefs seek Black Sphinx dates, weaving them into special dishes.

As much or more than flavor, local date heads laud the Black Sphinx’s texture. It has an ornate creaminess, dense as ganache or nut butter but with more fiber and without complete uniform smoothness. “I would say that, texture-wise, the Black Sphinx is a creamy date,” Frische says. Erica Schlather, a home date grower, agrees: “If you pick it early, it has a really creamy texture that spreads well on toast.”

During the heyday of Phoenix date culture, the Black Sphinx never had enough time or shelf life to grow from novelty to powerhouse. A 1942 article in Arizona Highways lists the five primary local rare date varieties. It omits Black Sphinx. By the late 1940s, recalls Benson, Metro Phoenix was in a phase of metamorphosis, “rapidly developing into housing.” Between 1950 and 1960, Phoenix’s population jumped from 107,000 to 439,000. As subdivisions replaced farms, Arizona’s date palm industry concentrated in more agricultural Yuma, home of the state’s $35 million date industry today.

In the early 1950s, Arcadia, home of Sphinx Date Ranch, was first subdivided into Mountgrove, a new development. Today’s vestigial, military rows of palms from the erstwhile Sphinx Date Ranch preside over big houses and teal pools, which still fruit in late summer. Schlather owns two quarter-acre plots in Mountgrove: her house and another she rents. Each plot has five Black Sphinx palms in the front yard, five in the back.

“My parents bought a piece of property here in 1972,” Schlather says. “They were looking for a home, and it just happened to be in a date grove.”

For 12 years, Schlather has harvested her Black Sphinx, enjoying the fruits of long-gone Sphinx Date Ranch. The tall, lanky palms present a logistical challenge, which she solves by deploying a construction-grade cherry picker to elevate, mechanically, to high-set date bunches. Because dates ripen variably, she has to make several elevations to each tree: when pollinating in March, when detangling dates in June, and when checking and picking in September.

Many residents of Mountgrove have palms, but few pick on their own. “None of my neighbors actually harvest their dates,” Schlather says. “We have a gentleman named Rejean Durette who goes around and harvests for them. He trims the palms, so it’s a win-win situation. He gives the neighbors about 12 pounds of dates per tree [and keeps the rest], and then they don’t have to pay $75 to have the tree trimmed.”

Schlather sells her Black Sphinx for $12 a pound. Depending on the seller, the varietal costs $8 to $15 a pound.

“This neighborhood is the only neighborhood that grows Black Sphinx,” Schlather says. Though date palms can fruit for 150 years, most do for 40 to 50. The Black Sphinx palms of Arcadia have already outlived these averages. They won’t be around forever, though their offshoots will produce offshoots, and the bygone orchard’s progeny may survive. For now, residents enjoy the continued bounty. “We have a block party every year,” Schlather says. “A lot of people in the neighborhood like to make date bread and cookies.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook