What Is the Point of a Pug—And 19 Other Dog Breeds?

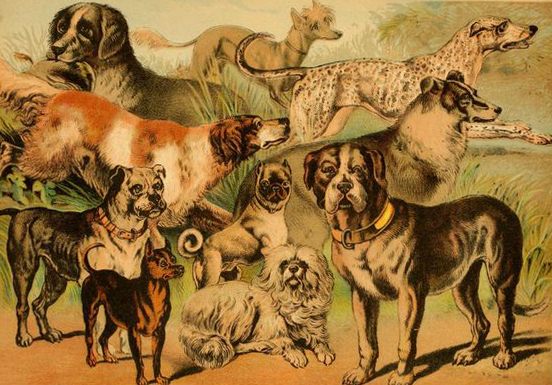

Best friends. (Photo: artvintage1800s.etsy.com/flickr)

It can be hard to look at a modern dog breed and see any sort of use for it other than a snuggle buddy. Dog breeds have been systematically manipulated by humans to exemplify certain traits which may or may not have any relation to the purpose that type of dog originally served.

What, in short, is the point of a pug?

Almost every single dog we love today once had a real purpose—and the ones that didn’t are sometimes the most fascinating. We surveyed the first 20 breeds of dog recognized by the American Kennel Club, and delved into their histories and earliest uses.

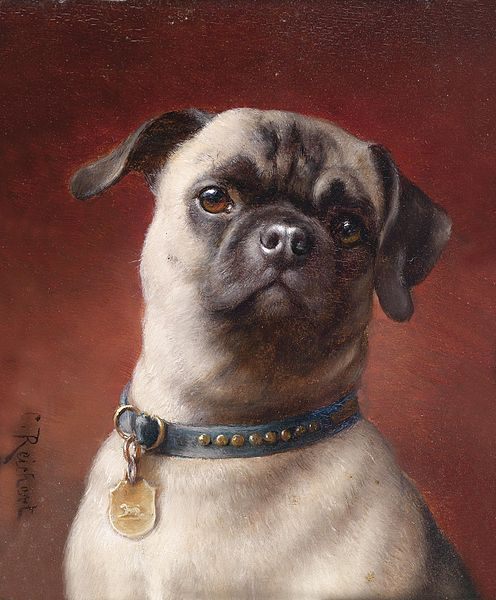

A 19th-century pug, by Carl Reichert. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Looking into dog breeds shows a huge variety, but not necessarily a very long history. Research indicates that domesticated dogs originated in Asia and spread to Africa somewhere between 9,000 and 34,000 years ago. (That same research indicates that the theory that dogs were descended from grey wolves may not be totally accurate; some DNA testing leans in the direction of the two having a common ancestor, meaning they’re more like evolutionary siblings.)

Dog breeds, though, are a tougher subject to pin down. Most loosely, we can define a breed as a group of dogs with very similar sets of physical and behavioral traits, which may have occurred naturally or from human intervention. DNA testing can sometimes help figure out these lineages; in many cases closely monitored breeds of dog exhibit a great deal of similarity amongst themselves and differences with other breeds. Various dogs have been claimed as “ancient breeds” at different times, and depictions of canines resembling greyhounds, for example, have been found in Egyptian tombs dating back to 5,000 years.

However DNA evidence suggests that a good deal of these “ancient breed” assertions are totally false. A 2004 study looked at genetic similarities between dog breeds and found distinct groupings corresponding to eras of intense human intervention into the bloodlines of dogs. By Roman times, rough groupings of dogs had begun to coalesce around specific purposes: guard dogs, herding dogs, and hunting dogs.

Puppy love. (Photo: artvintage1800s.etsy.com/Public Domain/flickr)

But the obsession with very specific physical and behavioral traits of dogs emerged in the Victorian era, from 1830 to 1900. In the latter part of the period, the American Kennel Club began recognizing specific dog breeds and rewarding them for purity. (That’s despite none of these breeds being very old at all.) England, Ireland, Scotland, and Wales became something of a hotspot for dog breeds; many of today’s most popular ones come from this time and those places.

Still, even if they only date back a century or two, dog breeds ended up the way they are for a reason. Until recently, dogs were more popular for specific tasks than as companion animals. It can be fascinating to see which traits emerged for which reason, in which parts of the world.

We researched the first 20 dog breeds recognized by the American Kennel Club (omitting some close relatives for the sake of keeping things moving). Where do these dogs come from? Why do they look or act the way they do?

Pointer (accepted by the AKC in 1878)

Sometimes known as the English Pointer to differentiate it from other pointers like the German Shorthaired Pointer, the Pointer was one of the first dogs recognized by the AKC. It’s an English breed, probably bred specifically in the 17th century from “gun dogs” brought to England from Spain.

Its name spells out why it was a successful breed: the English Pointer has a behavioral quirk that compels it to find prey animals, but instead of hunting them it stops and aims its muzzle at its quarry. This was a very useful trait for wealthy English hunters, tromping through moors in, presumably, fancy custom-made hunting gear in search of pheasants. It’s now become the hunting dog of choice in the southern United States, where it’s often referred to as a “bird dog.” In the U.S., it’s often used to hunt quail rather than pheasants, but still retains its bizarre and noble desire to locate, but not hunt, birds.

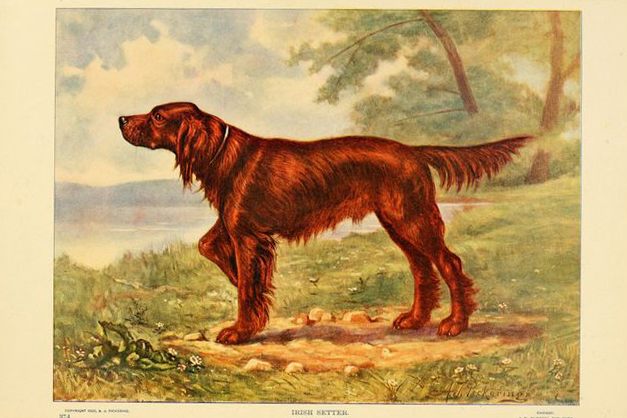

An Irish setter illustration from “The Book of Dogs; An Intimate Study of Mankind’s Best Friend”, published in 1919. (Photo: artvintage1800s.etsy.com/flickr)

Irish Setter (1878)

A longer haired, reddish dog, the Irish Setter is, like the Pointer, a gun dog with an instinct to point at prey. There are references to “Setters” in literature from the 16th century, but the Irish Setter is an excellent example of how the desire for old breeds can sometimes create a wildly inauthentic dog. With the increased movement around the world that arrived in the last couple of centuries, dog populations that had once been isolated found themselves anything but. That’s good for a breed’s health—more genetic diversity always means a healthier dog—but bad if you want to keep a dog looking like it did two hundred years ago.

In the 1940s, the Irish Setter was nearing “extinction” (that word, being, of course, sort of fanciful; there’s no such thing as extinction amongst dog breeds, and saying a breed is extinct is like saying humans with the first name “Maximus” are becoming extinct). So to “save” it, some Irish Setter enthusiasts began crossing some purebred Irish Setters with English Setters, to create a breed that looks and acts like a traditional Irish Setter, though of course now it’s a hybrid. Very controversial, in the breeding world.

Cocker Spaniel (1878)

The best guess of dog breed historians is that the Cocker Spaniel originated in Spain, hence its name, but the spaniel group is widespread and there are many competing theories about where it comes from. The “cocker” part is much easier: the breed was a rich man’s hunting dog meant to help with the hunting of woodcocks, a small game bird in the British Isles and, to a lesser extent, Europe. A small dog, it’s very good at scrambling into brush to scare a woodcock into taking flight, whereupon a hunter can shoot it. It also has a strong retriever instinct to bring the bird back to its owner. Useful!

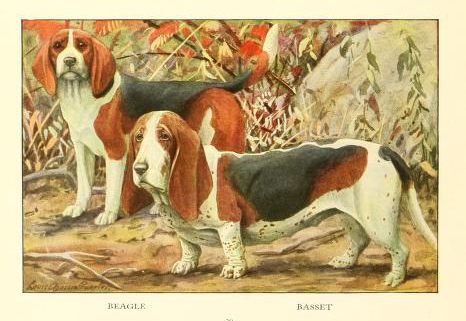

A Beagle and Basset Hound, (Photo: Internet Book Archive/Public Domain/flickr)

Basset Hound (1885)

The Basset Hound is a ridiculous-looking dog, short-legged and with droopy…everything. The history of the breed is better-known than most; this type of hound dates back to a collection of dogs owned by St. Hubert, a Belgian monk. It is a hunting dog, with a keen sense of smell, and gained fame in France for its ability to hunt rabbits and badgers and other ground prey.

The reason for its short stature is kind of weird; a study from 2009 that examined the history of short-legged breeds states that breeders wanted the dog to have shorter legs so people could more easily keep up with it during hunting sessions. (Of course, short-legged dogs are now prone to many muscular and spinal issues arising from that trait.)

Beagle (1885)

The modern Beagle dates back to the 1830s, in Essex, England; a pack owned and bred by a Reverend by the name of Phillip Honeywood is believed to be the origin of most modern Beagles. Honeywood’s beagles, though, probably had genes from a whole mess of other dog breeds, now mostly gone. Greyhound? Sure, maybe! The same Belgian dogs that eventually gave us the Basset Hound? Why not!

The Beagle is a hunting dog, a fairly slow runner but still pretty good for hunting hares, rabbits, and pheasants. It’s a good dog for hunters who prefer the hunt over the kill; other dogs are much better hunters, but the Beagle is a very nice companion.

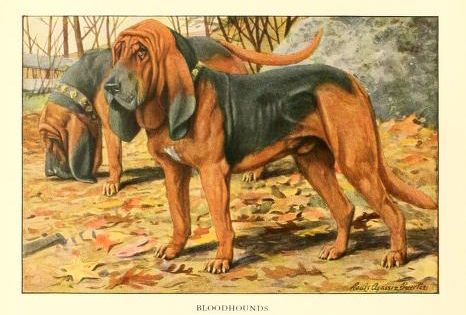

A bloodhound. (Photo: Internet Book Archive/Public Domain/flickr)

Bloodhound (1885)

This one probably also originated from those St. Hubert hounds, but its particular behavioral characteristics led it to be used for other tasks. Its sense of smell is legendary, and was used to track deer and wild boar, but it turns out the Bloodhound has a particular gift for tracking individual humans, which makes it a favorite of police forces and detectives.

Bull Terrier (1885)

A spectacularly weird-looking, muscular dog with a sort of egg-shaped face, the Bull Terrier is a mix of Bulldog and a now lost line of terriers. It’s a British breed with a darker history than most; by the mid-19th century, “blood sports” were highly popular in England, including ratting, bear-baiting, badger-baiting, and straight-ahead dogfighting. The Bull Terrier was ideal for these situations; placed in a ring, it’s a strong and tenacious fighter against rats, bears, badgers, or other dogs. No surprise, it can be a difficult do to train, and doesn’t get along well with other animals.

Collie (1885)

There are many breeds in the Collie family, from the Border Collie to the Shetland Sheepdog to the Australian Cattle Dog. Collies originated, probably, in northern England and Scotland, and are herding dogs, with strong instincts to control populations of stupider animals like sheep and ducks. This might seem a weird thing for a dog to do. After all, dogs are predators, so why in the world are they acting like parents?

It turns out herding is actually a predatory behavior that can become productive. Herding dogs are trained to keep groups of animals in specific spaces, and to obey commands to move the animals to specific places.

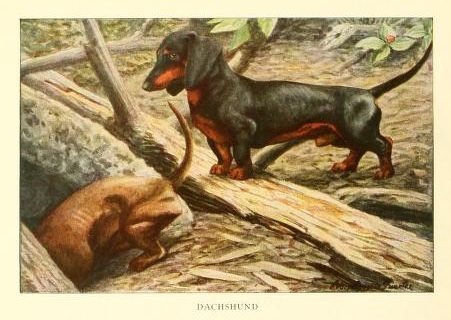

Dachshunds. (Photo: Internet Book Archive/Public Domain/flickr)

Dachshund (1885)

As its name suggests, the weiner dog originated in Germany. It was bred specifically for its skill at hunting badgers, whether in the wild or in badger-baiting events in arenas. It was also often used for hunting any kind of small terrestrial game—hares, rabbits, foxes.

There’s a wide discrepancy about when this breed came into being. It’s a mixture of a bunch of other hounds into one small strange package.

Mastiff (1885)

Mastiffs, of which there are several varieties, are enormous, often shaggy dogs that arose from any mountain where their services were needed, from the Pyrenees to the Himalayas. This is a broader category of several specific breeds, rather than a single breed that comes from a single place; dogs called Mastiffs all share a common ancestor in the Molossus, a Greco-Roman dog that no longer exists, but show variations in the thousand years or so that individual Molossus populations have been isolated. They are guard dogs, a variant of a herding dog that doesn’t control the herd so much as protect it from predators like wolves and coyotes.

Pug (1885)

An unusual one: the Pug is in the mastiff family, but very tiny, which makes it terrible as a guard dog. (Pugs are unlikely to strike fear into any predator’s heart.) They originate from royal China, where they were bred as companion dogs, a trait they retained when they were exported to Europe in the 16th century and later to North America. It’s one of the very few breeds that was originally bred to be a pet.

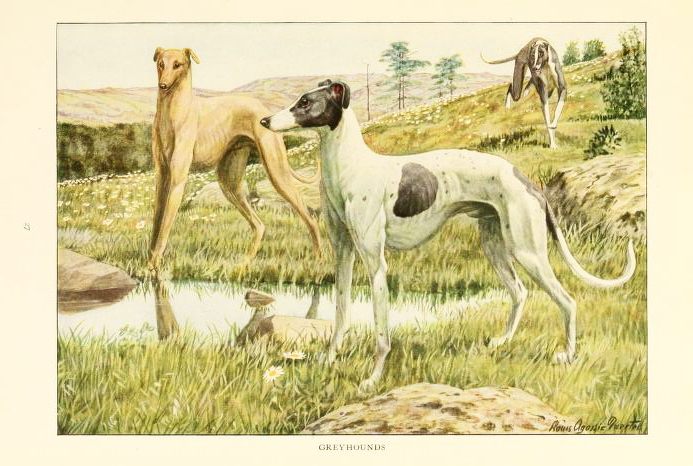

Greyhounds. (Photo: Internet Book Archive/Public Domain/flickr)

Greyhound (1885)

Dogs that look an awful lot like the Greyhound, with the distinctive barrel chest, narrow waist, and long snout, show up in depictions in Egypt from thousands of years ago, and so the Greyhound has often been considered a very ancient breed. But DNA evidence suggests this is just a coincidence, that Greyhound-type dogs (called sight hounds) popped up all across Europe sometime around the medieval period.

Greyhounds are used as hunting dogs but not for their keen nose, as Bloodhounds are: they’re most prized for their eyesight and foot speed, which allows them to pursue fast-moving prey like deer without losing it.

St. Bernard (1885)

Another mastiff type, the St. Bernard is a monstrously large and slobbery dog that comes from the Swiss Alps. They were bred originally for a unique purpose: their strong bodies and coarse fur makes them ideal search-and-rescue dogs in the snowy mountains of the Alps. These days, the St. Bernard has been crossbred with other mastiffs like the Newfoundland, reducing the differences between the various mastiff breeds.

Yorkshire Terrier (1885)

The tiny, cute Yorkshire Terrier originates in Yorkshire, in northern England, and dates back, as so many breeds do, to the mid-19th century. As Yorkshire was a manufacturing center, there was a need for a breed of dog that could take care of a necessary evil that comes with manufacturing: rats. The Yorkie is an ideal ratting dog, with a small stature and short legs to allow it to chase small prey.

Bulldog (1886)

The Bulldog, in its oldest form, was bred for use in blood sports, specifically bull-baiting, in Victorian England. A bull would be chained to a post, giving it maybe 20 or 30 feet of movement, and the dogs would be loosed nearby. They’d stoop low to the ground before attempting to deliver bites to the nose and face of the bull. (Bulls would often kill multiple dogs before succumbing.)

After blood sports were outlawed in England in 1835, it stopped making sense to breed this weird dog, but a few decades later, dog fanciers began breeding various dogs to emulate the physical traits the old Bulldogs had. From those newer Bulldogs come our modern ones.

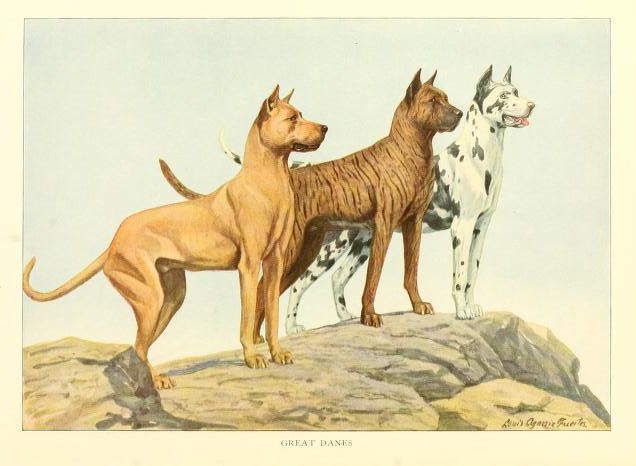

Great Danes. (Photo: Internet Book Archive/Public Domain/flickr)

Great Dane (1887)

The Great Dane is in the same mastiff family as the St. Bernard, but its origin is a little strange. The legendarily huge (but also very sweet) dog may or may not originate from Denmark, as its name would suggest; certainly there are very large dogs in the history of Denmark, but similar stories and depictions can be found in Germany and France.

These dogs are hunting dogs, but as anyone who’s met one can attest, they’re not much good at tracking or killing prey. Instead they were trained to use their massive size to hold down deer, boar, and other large game once it’s they’d already been caught by another dog, so the hunter could finish it off.

Different types of poodles (Photo: Internet Book Archive/Public Domain/flickr)

Poodle (1887)

A very intelligent, active breed, the Poodle originated in Germany under the very good name Pudelhund. It served a similar purpose as the Retriever does in England: it’s competent in water and has a firm retrieval instinct, so it’s ideal for fetching waterfowl. It even has webbed toes to help it swim.

The Poodle quickly became popular in France, the country with which it’s still often associated, and, even though it’s a capable working dog, is now often thought of as a frou-frou lap dog.

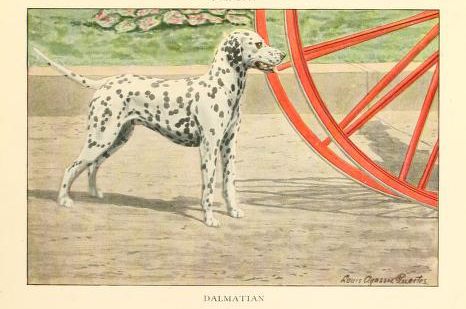

A dalmation. (Photo: Internet Book Archive/Public Domain/flickr)

Dalmatian (1888)

The famous firehouse dog is confirmed by most sources to have originated in Croatia, with the first discernible depictions dating to the early 17th century. (“Dalmatia” is a coastal region of Croatia.) Early uses of the dog varied; it seems the first Dalmatians were all-purpose dogs, sometimes used for hunting, sometimes for guard dogs, sometimes for companions.

Their use as firehouse dogs emerged in the 19th century in the U.S., where it was discovered that Dalmatians have a natural affinity with horses. Fire engines at the time were horse-drawn, and Dalmatians proved very capable of trotting alongside and in front of the engines to clear a path and find the way to a fire.

Pomeranian (1888)

The Pomeranian, a tiny fluffy purse dog, is actually in the Spitz family, a category of dogs that includes dogs as varied as the Alaskan Malamute (huge, sled dog), the Akita (traditional Japanese companion dog) and the Welsh Corgi.

Though it originally comes from a family of dogs around the Germany/Poland border, Queen Victoria of England is largely responsible for the Pomeranian. She continually bred smaller and smaller Pomeranians, eventually creating the standards that define the breed now.

What’s it good for? Well…not much. Other Spitz dogs serve a variety of purposes, from sled dogs to hunting dogs, but the Pomeranian, as soon as it became recognizable as such, was never anything other than a companion dog.

Golden Retriever (1925)

America’s dog if ever there was one, the Golden Retriever dates back to the Scottish elite in the mid-19th century. True to its name, the Golden Retriever is, first of all, gold, and second of all was bred for its instinct to go retrieve things. Originally, that was waterfowl: the rich Scots liked to stand at the sides of ponds and shoot ducks and geese, and the dog would do the hard work of swimming out into the pond to retrieve the bird where it had fallen.

Interestingly, there are three distinct types of Golden Retrievers, one from the UK, one from the U.S., and one from Canada. The UK Retriever is more muscular and with a broader face than the classic American dog. The Canadian version is like the American except slightly taller.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook