What Kind of Legal Rights Should Robots Have?

A new paper argues that courts need to keep up with technology, or risk angering our future overlords.

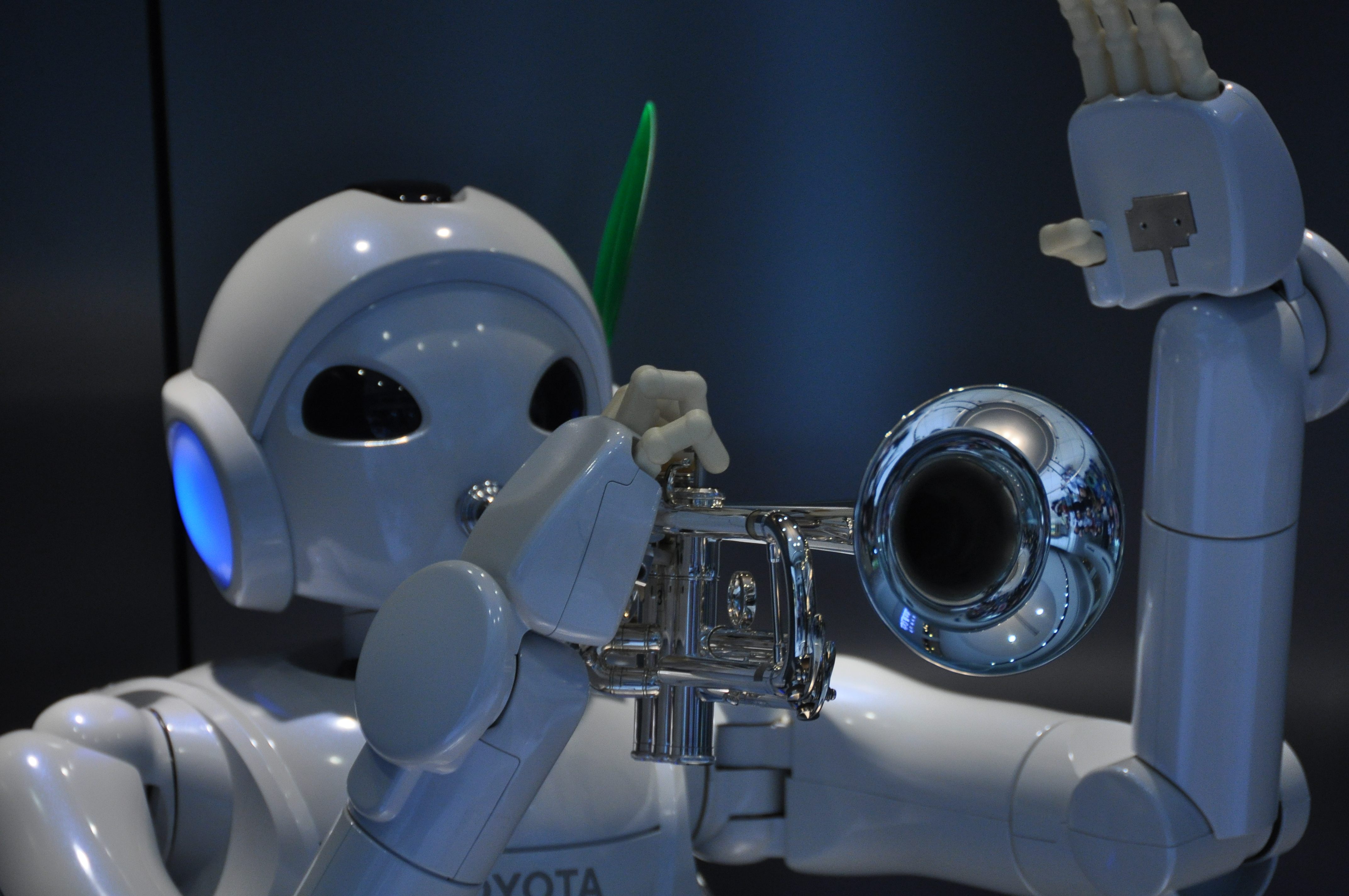

The trumpet-playing Toyota Partner Robot. Legally, we can’t call this a performance. (Photo: Marufish/CC BY-SA-2.0)

Robots. Are they people, too?

Science fiction has long consider the legal rights of artificially intelligent beings. But as robots become an increasing presence in our societies and industries, questions about the role of robots in legal decisions, how laws are applied to robots, and the concept of “robot law” itself have begun to emerge.

Ryan Calo of the University of Washington has recently published Robots in American Law, a legal research paper examining the judicial challenges presented by robots—and raising concerns that judges are not equipped to grapple with these new puzzles.

Calo argues that, unlike the internet of the 1990s, robots have already established a legal case history. The ’90s saw courts grappling with legal decisions transformed by the previously-unheard-of capabilities of the internet, such as instantaneous transfer of goods and services across borders. Robots, however, have existed in some form for decades, giving them the opportunity to be involved in court cases long before the current explosion in robotics. In three parts, Calo presents a series of case studies, first discussing “robots as objects of law,” moving on to instances where robots were used as “metaphors or analogies that actually drive the decisions of courts,” and finally hypothesizing how existing case law may impact the development of robotics law.

The cases Calo presents provide a fascinating look at questions that seem to be taken straight from the pages of OMNI magazine. Let’s briefly summarize the highlights:

*Comptroller of the Treasury v. Family Entertainment Centers asked, “Do the life-sized animatronic puppet performers at Chuck E. Cheese qualify as a live performance?” The courts answered, “No,” equating Chuck and his pals to an “embellished jukebox”.

*Louis Marx & Co. and Gehrig Hoban & Co., Inc. v. United States forced the courts to decide if a “mechanical walking robot” qualified as an animate object, thereby allowing it to be imported at a lower rate. The court pulled out its dictionaries and decided that, based on the respective definitions of “robot” and “animate,” an “automaton that performs all hard work” could not be considered to be “endowed with life.”

*Robotics law collided with maritime law in Columbus-America Discovery Group, Inc. v. The Unidentified, Wrecked, and Abandoned Vessel, S. S. Central America, which asked: if a submersible robot grasped an object in the shipwreck, could Columbus-America be said to have assumed control of the wreck? Although salvage law tradition dictated that human divers must approach the vessel, the court decided that the extreme depth of the wreck (nearly 1.5 miles below the surface), meant that robotic “telepossession” was sufficient.

So, to summarize the above: robots can’t give performances, aren’t animate objects, but can take possession of items as extensions of their operators. The entire paper is full of interesting, sometimes contradictory, cases, and well worth reading. But the varying precedents established combined with judicial metaphors advancing the idea that robots inherently lack autonomy, may create difficulties as robots—and, inevitably, legal cases involving robots—become more and more common and these narrow decisions and definitions become less and less accurate.

“The mismatch between what a robot is and how courts are likely to think of robots will only grow in salience and import over the coming decade,” Calo writes. He emphasizes the importance of exploring existing case law and establishing new institutions and agencies to provide knowledge and information to help guide courts. Writer Hallie Siegel echoes these concerns in her essay for Silicon Valley Robotics. She writes:

Robots are challenging precisely because they can’t be neatly defined by the legal structures we depend upon to keep us safe. The only answer we have is to clarify our definitions of robots and autonomy — but that requires a partnership between those who really understand the technology and those who really understand the law.

As Siegel concludes, we should be thankful scholars like Ryan Calo are already considering these issues. It certainly seems like we’ll need far more than three laws of robotics.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook