The ‘Father of American Neurology’ Prescribed Women Months of Motionless Milk-Drinking

Virginia Woolf and Charlotte Perkins Gilman were both patients of his infamous rest cure.

For over a month, “Mrs. C” laid in bed, gulping down quarts of milk. Aside from occasionally sitting up and relieving herself, the 33-year-old New Englander remained horizontal. She had been deemed sick, or “wearied” at the least. But according to Dr. Silas Weir Mitchell, his strict “rest cure” regimen had her on the mend. By the end of the month, she’d gained 40 pounds and a spot among his most successful cases.

The rest cure that Mitchell pioneered rose to surprising popularity in the late 1800s, and several physicians adopted and practiced the treatment for decades. Only later did it become a textbook example of the disturbing nonlinearity of American medical progress, the quackery that can live alongside rigorous medical innovation.

In the 19th century, the practice of psychiatry was rapidly evolving, and Mitchell, a neurologist from Pennsylvania, was at its forefront. The Civil War created a fresh need for young physicians willing to cut their teeth on the battlefield, particularly psychiatrists able to work with wartime trauma and surgeons treating injuries of the nervous system. New front-loading rifles and flattening bullets called “minnie balls” burst through bone and tore across tissue, leaving soldiers with devastating wounds treated by rapid amputation. Arms and legs were removed in mere minutes, and by the war’s end, tens of thousands of limbs had been amputated.

Mitchell found his place on the battlefield as a young surgeon, working at a specialty ward in Philadelphia. He quickly took an interest in the not-yet-understood “nerve injuries” of amputees who experienced inexplicable, ghostly pain lingering where an arm or leg had once been. Mitchell wrote extensively on the subject, and coined the phenomenon “phantom limb syndrome.” As a quickly ascending physician in the fledgling field, he was awarded the title “Father of Modern American Neurology.”

But Mitchell’s interest in “nerve injuries” began to branch beyond the battlefield. After the war, he became increasingly concerned with the neurological and biological effects of a technologically advancing America. “Have we lived too fast?” he asks in his 1871 book, Wear and Tear. The “cruel competition for the dollar,” he posits, along with the “racing speed which the telegraph and railway … introduced into commercial life” had planted something insidious in society, as well as within the human body.

American progress, he believed, was not without its neurological consequences. Something must be amiss among the urban elite, who were at the crux of rapid change and hurtling trains. Modernity, he posited, could deplete finite stores of “nervous energy,” leaving bodies and minds exhausted and sick. And when people overexert their minds, the only way to return to normalcy was to rest.

According to the neurologist, a person sick with “neurasthenia,” a term coined by a contemporary of Mitchell’s, might show symptoms ranging from headaches to lethargy, or weight loss to impotence. For men, the antidote was simple: Go West, chop some wood, maybe even cook some mannish meat over a rip-roaring fire. In a way, it was the 19th-century, professionally-prescribed analogue to a trip to the dude ranch.

But the cure was not quite so simple for women. Ladies, too, found themselves impaired by the pace of modern life, or, at least, swept up in the medical trend. More specifically, white, upper-class, educated women came to dominate Mitchell’s patient demographic. Women who occupied privileged positions like this, who were often writers and artists, had been increasingly afforded time outside of the home, the opportunity to socialize, and higher education. But using their minds so extensively, Mitchell believed, could easily deplete their energy and fry their fragile nerves.

Mitchell proceeded to prescribe the rest cure almost exclusively to these women—“nervous women,” writes Mitchell, “who, as a rule, are thin and lack blood.” And the way to quell the overexerted brain and depleted blood supply of a woman was to, essentially, prescribe her a long, milky, much-needed rest.

According to author and historian Dr. Jennifer Lambe, a number of symptoms brought women to Mitchell. Often, they looked like what many psychiatrists at the time would call manifestations of “hysteria,” an intense mixing of the psychological and the somatic. Some patients complained of anxiety, fatigue, and even blindness. Others had stopped speaking entirely.

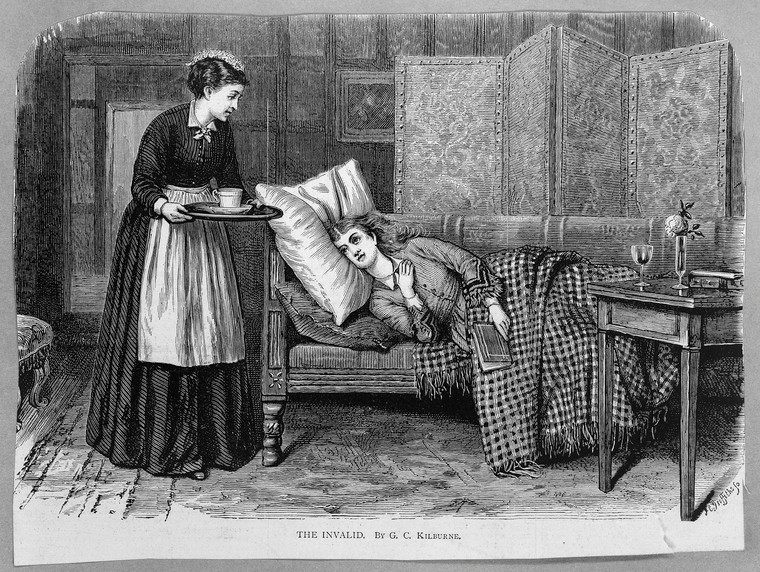

Though customized to cater to each patient’s symptoms and severity, the treatment typically entailed six to eight weeks of absolute bed rest. Patients were most often placed in complete isolation, interacting only occasionally with a nurse. “I would describe it as a kind of hibernation,” says Lambe. “Combined with the pre-hibernation period, when, for instance, a bear has to eat a lot beforehand.”

During the first phase of the cure, Mitchell typically forbade his patients to rise at all, with the exception of sitting up for spoon-feeding or getting up to relieve themselves. But when dealing with particularly extreme cases, Mitchell writes, this period of total repose could be stretched to months. Once they were allowed to sit up more frequently, however, reading, writing, drawing, or doing anything that might require using the mind remained forbidden.

But bed rest was only one aspect of the treatment. Mitchell prescribed his patients frequent “massages” to stimulate the muscles without exhausting them. These, however, were incredibly vigorous and were likely far from relaxing. “The whole belly is shaken by a rapid vibratory motion of the hands,” writes Mitchell, “to which is sometimes added succussion by slapping with the flat or cupped hand.” Massage could be supplemented with the passage of an electric current through the leg muscles, belly, back, and loins, apparently to stimulate muscles and provide what he referred to as “painless exercise.”

Perhaps the strangest aspect of the treatment was its strict overfeeding regimen, which was heavily reliant upon milk. Mitchell writes that it was nearly impossible to treat any case without the dairy product. It was often doled out exclusively to the resting patient for the first few days, and later supplemented with high-fat, highly caloric meals. As the case progressed, Mitchell suggested, milk might be swapped out for various “children’s foods,” such as malted milk or “Nestle’s food.”

There’s something deeply disturbing about this infantilizing, womb-like treatment. The milk, consumed in excess, gave rise to extreme sleepiness, he writes, as well as “a white and thick fur on the tongue, and often for a time an unpleasant sweetish taste in the early morning … neither of which need be regarded.”

Mitchell writes with apparent satisfaction about his successes in his essay, Fat and Blood. Mrs. C’s “gain in flesh about the face” and resumed menstruation after years of missing periods was evidence enough for the neurologist that fat, blood, and vitality had been restored. Soon, other physicians adopted the practice, which seemingly encouraged Mitchell, or at least allowed him to absolve himself of full accountability. “I am fortunate now in having been able to show that in other hands than my own, this treatment has so thoroughly justified itself as to need no further defence or apology from its author.”

But there’s a glimmer of self-awareness in the book’s final, somewhat ominous, conclusions. Perhaps the physician intuited that his actions would be controversial. “I am now more fearful that it will be misused, or used where it is not needed, than that it will not be used,” he writes, “and, with this word of caution, I leave it again to the judgment of time and my profession.”

With time, condemnation arrived. Charlotte Perkins Gilman, author and patient of Mitchell, wrote The Yellow Wallpaper, a fictionalized account of her experience undergoing treatment. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the main character is driven to madness. Virginia Woolf, too, was prescribed the rest cure by her gynecologist, one of Mitchell’s British contemporaries, and wrote passionately against the practice.

It would be easy to describe this as yet another case of systemic, patriarchal oppression. But Lambe points out that there was also a more complex dynamic at play. Women, it seems, weren’t always entering the position of patient involuntarily. Being part of an advancing society, suggests Lambe, often begets a bemoaning of it. In other words, there’s a glimmer of pride in experiencing the afflictions associated with technology and modern life, because it also reflects privilege and status.

The women who were treated by Mitchell’s cure belonged to an elite group that could afford to engage with, and bemoan, technological and social progress. While it was strange and suffocating, it was also likely somewhat stylish. Lambe points out that there were countless women, often immigrants or from poor populations, who could never have afforded private psychiatric care. Instead, these women often ended up in public asylums, or received no care at all, and their suffering and part in the history of American psychiatry stayed out of sight.

It wasn’t until the 20th century that the catch-all diagnoses applied to women began to decline. Bed rest wasn’t fully debunked until World War II, when physicians noticed that extended periods of repose weren’t incredibly effective in helping soldiers recover. Soon after, studies revealed that immobilization was, in fact, harmful to the body, negatively affecting every major organ system. Eventually, the rest cure was put to rest, a dark blip on the evolution of neurology, and a warning that science and pseudoscience, the Father of American Neurology and the inventor of the rest cure, can coincide.

But the core idea behind the cure, Lambe suggests, is not so far behind us. “You can find analogues in today’s wellness culture,” she says, “such as the retreat, where you remove yourself from all the things that are ailing you, eat a very specific, austere diet, and reboot.”

Who, after all, hasn’t itched to ditch the ever-increasing pace of work and inescapable chatter of social media? Overworked and overstimulated, we’re told to take breaks, seek out quiet spaces, replenish the body, and get enough sleep. If the world outside can’t slow down for us, we can do it ourselves, by reclining on the couch (perhaps spoon-feeding ourselves a pint of ice cream), turning on Netflix, and turning off the mind.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook