America’s Pistachio Industry Came From a Single Seed

A “plant explorer” helped establish the crop in California.

In 1979, a group of Iranian college students stormed the American Embassy in Tehran, where they took dozens of hostages. The resulting crisis dominated relations between the two countries, influencing politics for generations. But the tensions proved a boon for American pistachio production. When the American government slapped a retaliatory embargo on Iranian pistachios, California’s nascent pistachio industry exploded, to the point that Iran and the U.S. now are neck and neck for the accolade of the world’s top producer.

From a botanical perspective, this was a remarkable turnaround. Because only half a century earlier, a “plant explorer” named William E. Whitehouse had seeded the entire industry. In what is now considered “the single most successful plant introduction to the United States in the 20th century,” he traveled to Iran and brought back one very important seed.

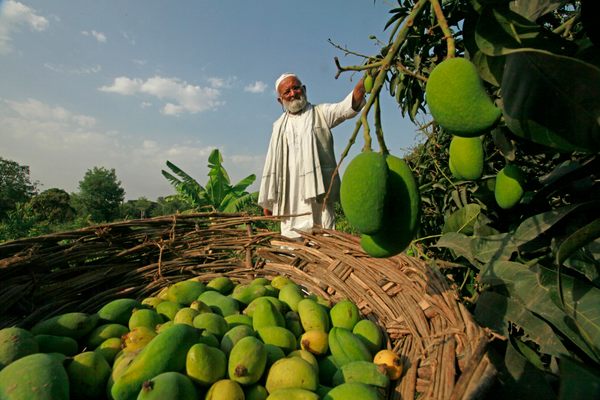

While areas in Syria, Turkey, and Sicily have long produced pistachios, Iran’s climate is uniquely suited to the finicky crop. That’s because pistachio trees like extreme conditions—many varieties have deep roots and thick leaves that allow them to grow in hot, drought-prone areas, but they simultaneously require cold winters to fruit. According to Louise Ferguson, a pomologist and pistachio expert at UC Davis, the trees can survive in saline soils that other fruit trees would find insupportable.

The Iranian town of Rafsanjan, in the province of Kerman, is a pistachio-producing powerhouse. Its desert-like climate and high, chill-inducing altitude make it ideal for pistachios. Most Iranian pistachio farmers hail from Rafsanjan, says Leili Afsah Hejri, a food scientist who specializes in pistachio machinery at the University of Merced. She herself is the fifth generation of a pistachio-producing family from the town.

This concentration of nut knowledge points to another difficulty. Pistachio trees take about a decade to mature, and after they do, many pistachios only produce their trailing bundles of fruit in alternate years. Growing this nut is an investment. (Also, the pistachios we eat aren’t true nuts; they’re seeds.)

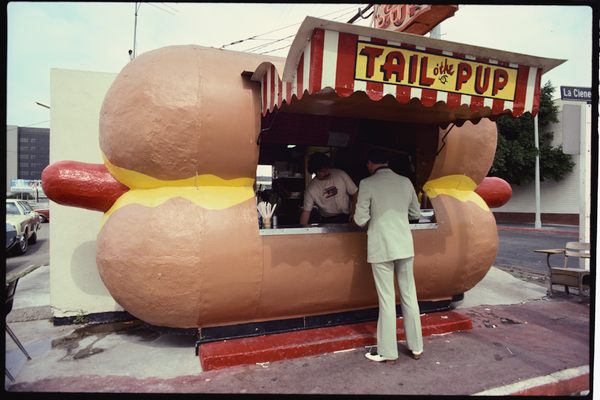

These unique requirements are what make pistachios more expensive than most other “nuts.” In fact, they only came to the United States in the late-19th century with Middle Eastern immigrants to New York. But they were imported as “edible nuts,” says Ferguson, “so those were processed and non-fertile.” For decades, imported pistachios were dyed red, as part of an effort to hide blotches. Companies loaded them into train and bus station vending machines, where snackers paid a nickel for a dozen. For years, these vending machines accounted for the vast majority of pistachios sold in the United States.

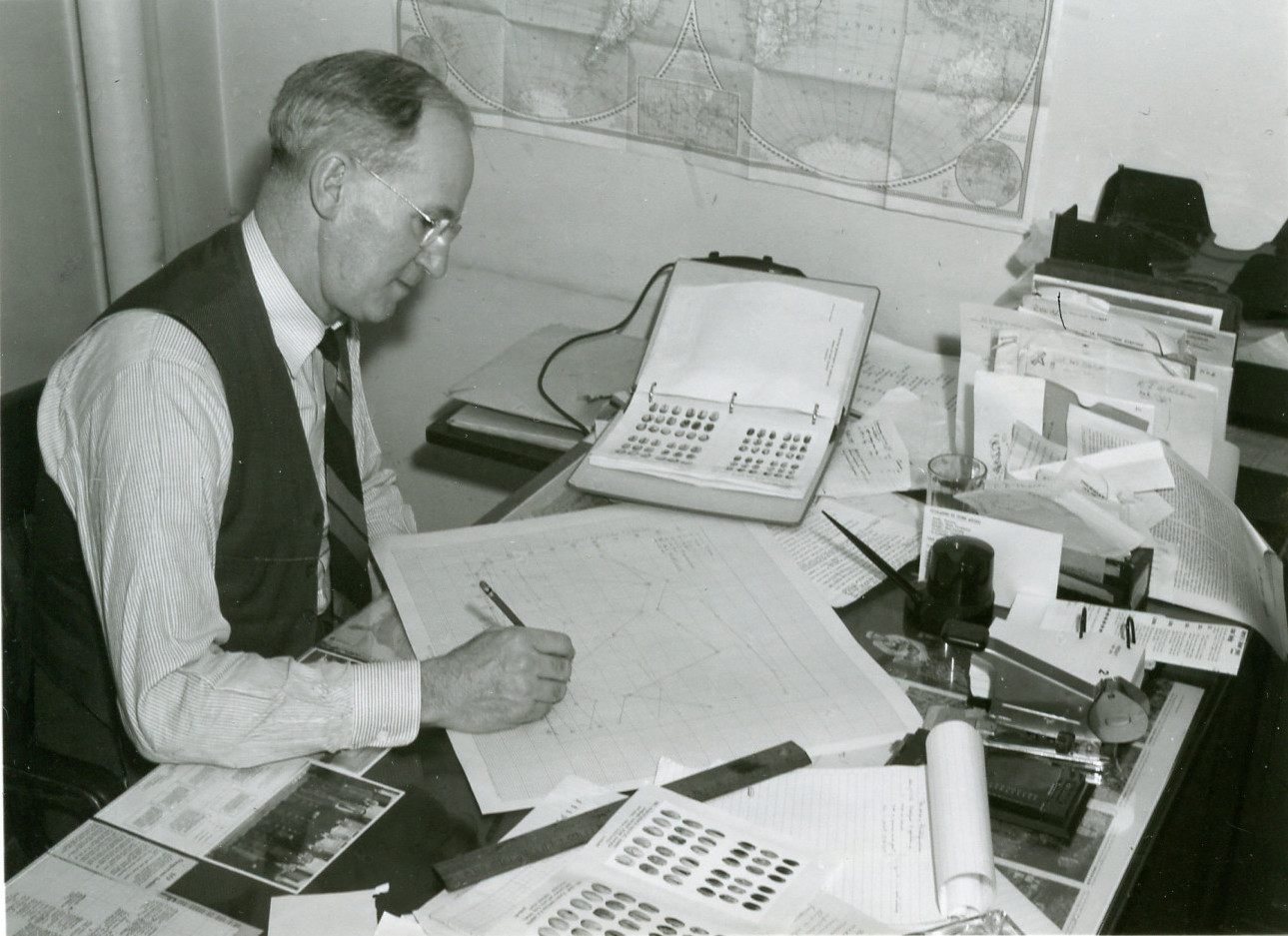

The botanically inclined experimented with planting the precious trees in the American South and California. But the true start to pistachio domination came with the founding of the Chico New Plant Introduction Station in the early 20th century. Paraphrasing a favorite sci-fi quote, Ferguson says that part of the USDA’s goal is to explore “new worlds” of plants. In 1929, the station sent William E. Whitehouse, a deciduous tree researcher, to Iran. His mission: to collect pistachio seeds for planting.

For six months, Whitehouse searched, gradually collecting 20 pounds of different pistachios. Some came from the Agah family in Rafsanjan, who, Hejri notes, is still the main producer of pistachios in the area. After Whitehouse’s return to Chico, the station planted and evaluated 3,000 trees. Only one pistachio rose above the others. Sourced from the Agah orchard, it was given the name “Kerman.”

“That became the basis of our industry,” says Ferguson. Its virtues are many. “They’re round in shape, they’re unstained and clean-shelled, firm, crispy, purple and yellowish-green kerneled … ” Hejri rhapsodises. Provided with a nearby male “Peters” tree for fertilization, the Kerman would become the American pistachio. A female mother tree at the Chico research station, planted around 1931, became the source of “all commercial pistachio trees in California,” writes journalist Eric Hansen. In Iran, more than 50 varieties are cultivated, not counting the great number of wild pistachios. But even today, the vast majority of California’s pistachio trees are Kerman.

Eventually, California’s San Joaquin Valley would become the Rafsanjan of America. Summer temperatures in the national breadbasket can be roasting, but the “winter fogs serve the same purpose that chill from altitude served in Iran,” Ferguson notes.

But progress was slow, and pistachio planting stayed small-scale for decades. Whitehouse kept his eye on the pistachio as a potential money crop for California, publishing a paper on the subject in 1957. He noted that while the Iranian pistachio had been an important local crop for hundreds of years, its value as an export was recognized only in the first half of the 20th century, “with new plantings keeping pace with the rapid increase in American consumption.” But despite the demand, it took two more decades for the first commercial crop of American pistachios to be harvested in 1976.

Yet the true reason for the success of the American pistachio was political, rather than botanical. In the early ‘70s, California growers turned to pistachio plantings when citrus and almond groves were increasingly taxed—an effort aided by the Central Valley Project bringing needed water. Then, a decade later, the friction with Iran resulted in sanctions on Iranian pistachios. “This California pistachio is brought to you courtesy of the Internal Revenue Service and the Shah of Iran,” the New York Times noted in 1979. Even after sanctions were lifted, Ferguson adds, the pistachio industry “organized very quickly and got a 300 percent tariff against the Iranian product.”

Whitehouse died in 1982, less than a decade after pistachios became a commercial crop. Though considered the father of the American pistachio industry, he’s never received much renown for his accomplishments. He did, however, have a pear (of all things) named in his honor, and received the first very-new Pistachio Association’s Annual Achievement to Industry Award in 1977. That year, only 1,700 acres were planted with producing trees. By 2012, that number had ballooned to 178,000 acres. It seems like small pistachios in light of his accomplishment: laying the groundwork for an industry worth $1.6 billion in California alone, and finding a new home for an in-demand tree.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook