Why British Royal Navy Sailors Preferred Their Booze on Fire

The alcoholic “proof” system dates back to this centuries-old practice.

Nowadays, a flaming alcoholic beverage is either the handiwork of a skilled bartender or a terrible mistake. But just two centuries ago, this ritual was commonplace among members of the British Royal Navy. Setting fire to rum helped sailors regulate their spirits—and perhaps, find a small sense of control amidst an otherwise chaotic life at sea.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, life aboard a Royal Navy ship entailed brutal battles, unavoidable disease, and, to deal with it all, an inordinate amount of alcohol. To keep the seamen fed, hydrated, and in high spirits, the Victualing Board ensured that the fleet was supplied with an appropriate amount of salted meats, cheese, biscuits, and booze.

Initially, beer was the British Navy’s drink of choice. Water spoiled at sea, so sailors were allotted a whopping gallon of the brewed beverage each day. The Victualing Board owned its own breweries, and experimented with a few different brews, including stronger ales that could be diluted at sea, and spruce beer, believed to help ward off scurvy. But even beer didn’t hold up so well in the heat. After sitting in the damp, hot bowels of the ship, the wooden kegs would grow mold, turning the beer rancid. The Navy needed a more resilient spirit, one that could withstand time and temperature—and, perhaps, boost the bravery of the sailors, too.

Rum wasn’t the immediate first choice. The Royal Navy experimented with brandy and arak, a particularly strong distilled drink from the Middle East, introduced by the East India Company. But as the Triangular Trade and slave labor in the Caribbean made rum more accessible, and an important British business interest, it became the beverage of choice among the fleet.

Sailors received a “tot” of rum, equivalent to nearly half of a pint, each day. It could be drained on the spot, taken with lemon or lime juice to prevent scurvy, or used to settle debts between sailors. Rum was even prescribed to treat various ailments, such as scorpion and spider bites. Though revered for its supposed medicinal properties, it frequently led to intoxicated injuries, alcohol poisoning, and death. William Warner, a naval surgeon, observed in his medical notes, “drunkenness nowadays in the navy kills more men than the sword.”

Despite the dangers, sailors were more concerned about not being drunk enough. Wary that the ship’s purser might be serving watered-down rum, the seamen needed a quick, simple system to test the legitimacy of their spirits.

So, quite literally, they brought the fire. Harking back to a 16th-century system used by British tax collectors when calculating liquor tariffs based on alcohol content, the sailors implemented a resourceful (and rather dramatic) proof system. First, a few grains of gunpowder were mixed in with a small sample of allotted rum, and then set to a flame. If the liquid caught fire, the flame was “proof” that it wasn’t a diluted tot. If there was no reaction, the purser would face the fiery wrath of a shorted crew.

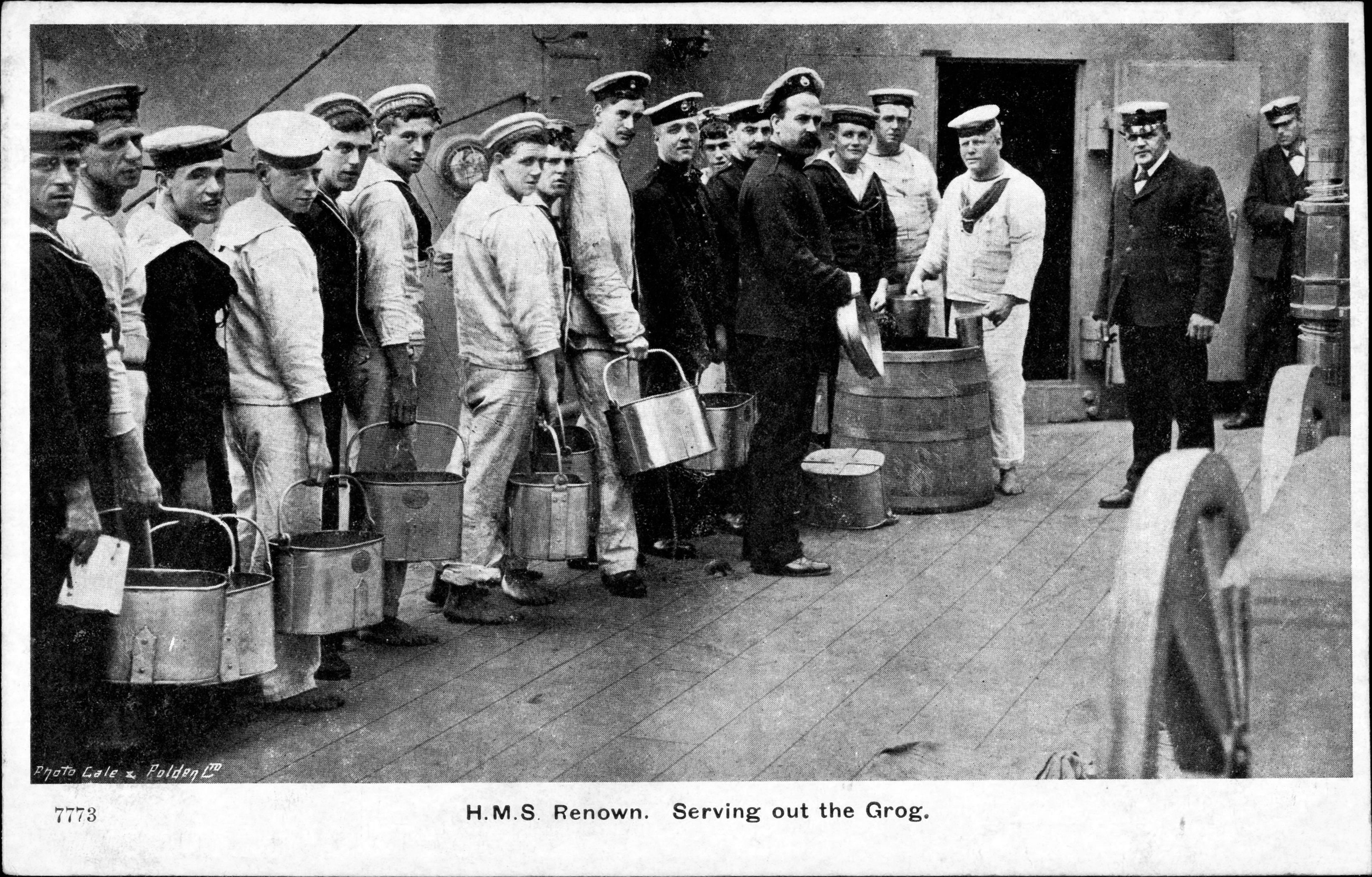

By 1740, an admiral by the name of Sir Edmond Vernon saw the constant drunkenness of his fleet as a bit of a problem. In an attempt to sober up the unruly troops, he established a new rule buffering the sailors’ buzz. From then on, the purser of each ship was required to dilute the rum with water, giving birth to a booze dubbed grog, which was doled out in two daily servings. The moniker is likely taken from Old Grog, a nickname attributed to Vernon for the infamous, gum-stiffened grogram coat he sported.

Though diluted, the new drink didn’t exactly usher the British Navy towards immediate sobriety. The total amount of rum between the two servings of grog supposedly still neared eight ounces. Over time, however, things began to shift. The invention of the hydrometer in 1816 dispelled the need for such an explosive proof method. Eventually, the temperance movement of the 19th century began curbing the sailors’ rum intake. By the 1950s, the rise of technology and advanced weaponry forced the Royal Navy to prioritize mental precision over drunken valor. On July 31, 1970, Black Tot Day marked the official eradication of rum from the British Navy, much to the chagrin of the sozzled seafarers.

Despite the gradual disappearance of torched tots and unadulterated intoxication aboard Great Britain’s naval ships, much of the language from the old maritime proof system still exists today. In England, spirits comprised of more than 57% alcohol (the lowest concentration that would catch fire) are considered to be “naval strength,” or overproof. The United States, too, uses proof terminology, though it varies slightly from the British vocabulary: A drink that contains 50% alcohol is considered “100 proof.” Even the word “groggy” harks back to the disoriented feeling one might get from guzzling too much grog—which, any 18th-century sailor might tell you, is an unsettling state to be in when dealing with explosive drinks.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook