Ancient Hot Pots Helped Hunters Survive the Siberian Ice Age

16,000 years later, they still contain traces of cooked meat and fish.

Siberia was probably not the ideal place to live during the late Ice Age. But new research indicates that those residents were perhaps toastier than we might think. As far back as 16,000 years ago, inhabitants of the perilously icy landscape had figured out how to cook meals in early “hot pots,” heat-resistant ceramics that preserved precious nutrients and warmth.

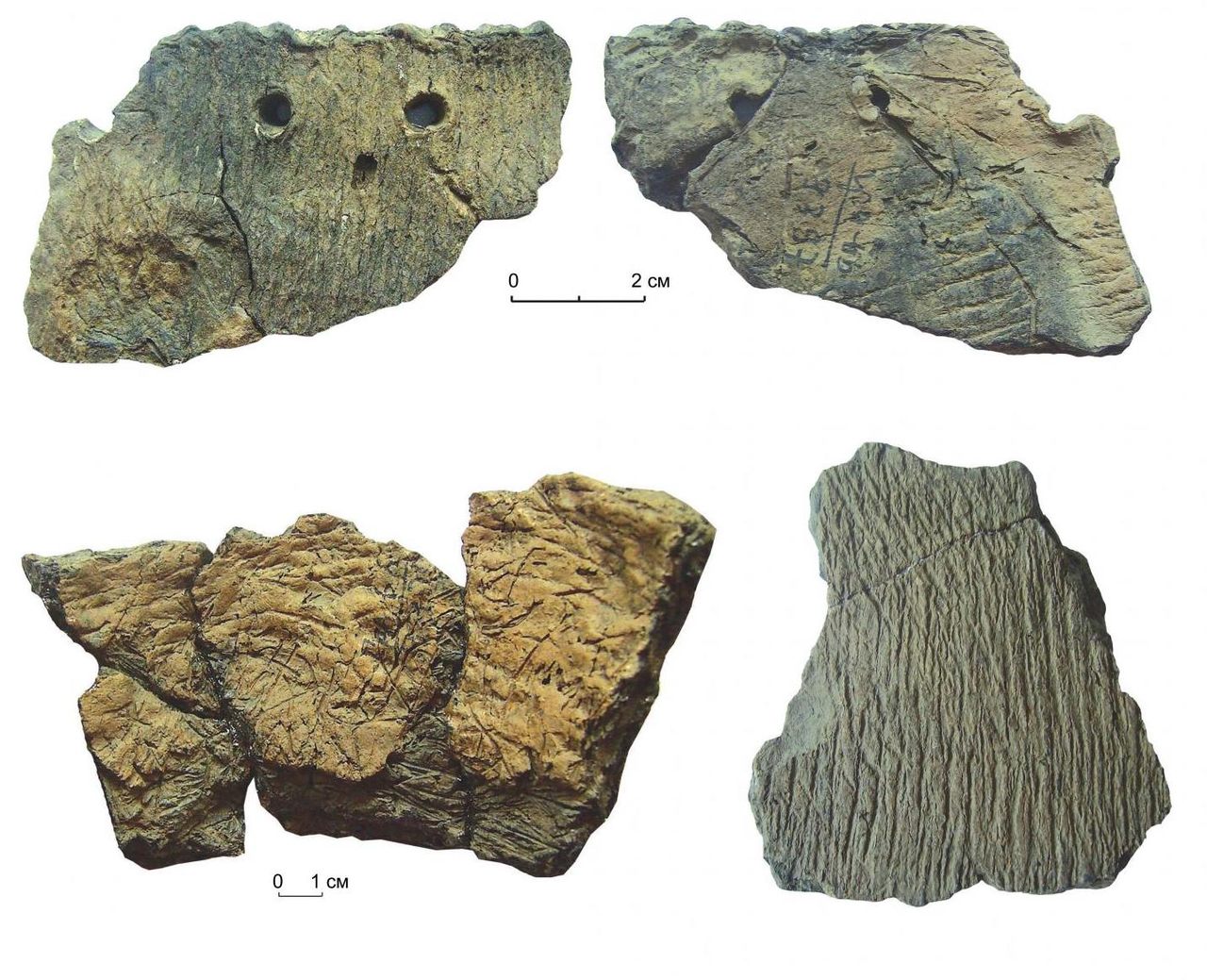

An international team of researchers, who published their findings in the journal Quaternary Science Reviews, analyzed pieces of pottery discovered at various sites along the Russian side of the Amur River, which forms part of the border between Russia and China. Those pieces range in age from 16,000 to 12,000 years old, and were already known to be among the oldest pieces of pottery in the world. For this study, however, the researchers undertook new chemical analyses of the sherds, allowing them to advance more confident theories regarding the pottery’s purpose.

At the University of York’s BioArCh Lab, in northern England, researchers extracted fats and lipids that provide new insight into the diets of Ice Age Siberian hunters. The pots from the Middle Amur River, they found, primarily cooked meaty meals, allowing that society to glean all-important bone grease and marrow from meat that might have otherwise been scarcely available. Meanwhile, some of the pottery found along the Lower Amur River—at sites associated specifically with the Osipovka culture—contained traces of cooked fish. (The researchers suspect that the fish was likely salmon.)

The discovery of these fishy traces was crucial because it helped draw meaningful connections between different cultures. The same research team had also collected ancient pottery from islands that are now part of Japan, and chemical analysis of that pottery revealed an “identical scenario” to what had been found on the Lower Amur—namely, that the pottery had been used to cook fish during the same period. Taken together, the different sites provide evidence of a so-called “parallel process of innovation,” in which different cultures mirror each other’s progress despite never coming into contact. Given the age of the cooking vessels from all the sites, the researchers theorize that the early pottery of each developed in response to the extreme climatic conditions of the late Ice Age.

In a statement, Peter Jordan, an author of the study and an archaeologist at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, said that the findings “suggest that there was no single ‘origin point’ for the world’s oldest pottery.” That indicates, he continued, “‘parallel innovation’ during a period of major climatic uncertainty, with separate communities facing common threats and reaching similar technological solutions.” Sounds like something we could use a bit of today as well.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook