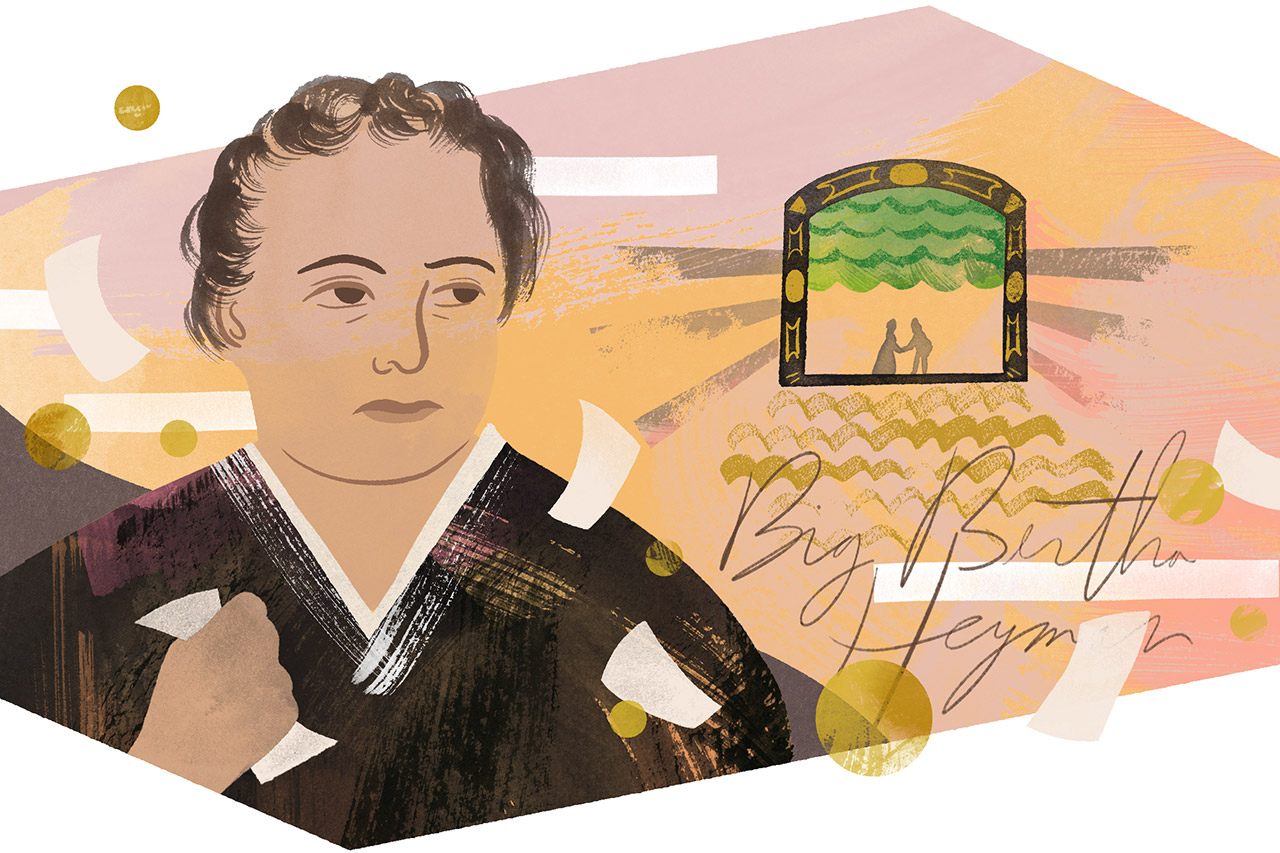

The Prussian Grifter Who Swindled Her Way to Her Own One-Woman Show

Bertha Heyman lived a life in and out of jail and on and off the stage.

Everyone loves the story of a good grift, from brilliant ruse to inevitable downfall. This week, we’re ushering in the spring of the swindle by highlighting the stories of the greatest con women in history. Previously, we heard about Barbara Erni and her very special trunk, Madame Rachel’s dangerous cosmetics, Thérèse Humbert’s imaginary millionaire, and the fake Princess Caraboo.

Bertha Heyman never stopped swindling men—even from behind bars. While serving time on Blackwell’s Island, New York, in the early 1880s, she managed to befriend and con a man out of his entire life savings of $900 (the equivalent of $20,700 today). But unlike other scammers of her day, she preferred to target those who really should know better. “The moment I discover a man’s a fool I let him drop,” she told a police chief in Jersey City in 1883 after one of her many, many arrests, according to Kerry Segrave’s Women Swindlers in America, 1860–1920. Heyman added: “But I delight in getting into the confidence and pockets of men who think they can’t be skinned. It ministers to my intellectual pride.”

Born Bertha Schlesinger in Prussia, she came to the United States in 1878, according to Thomas Byrnes’s 1886 Professional Criminals of America. She married twice—once in New York and once in Wisconsin—and took on the surname of her second husband, John Heyman. According to crude descriptions in newspapers of the day, Bertha was built like a tank, but what she lacked in society-approved feminine wiles, she more than made up with in charisma.

Bertha pulled off an impressive number of capers over the course of her criminal career, most of which hewed to a similar core premise. Bertha would claim to be fabulously wealthy woman who was having trouble accessing her abundant funds, and if a kind man would simply lend her a small cut of money she would access her estate and pay them back handsomely. Think of it as a 19th-century advance-fee email scam.

For some years, Bertha drifted around New York stealing watches and jewelry, forging checks and bonds, and, consequently, moving through the New York Penitentiary as if she were in a revolving door. In 1888, she moved to San Francisco with a man she said was her son, Willie Stanley. She approached Rabbi A.J. Messing, an acquaintance from her Prussian childhood, and explained that she had made the grave mistake of marrying a husband who was not Jewish (and, conveniently, deceased). She said he left her an enormous fortune, but she now wished to marry a man within her faith and needed help finding a husband. Fortunately, Messing’s brother-in-law, Abraham Gruhn, was quite taken with Bertha. He proposed in a matter of days, according to the San Francisco Examiner.

And so Bertha became joined the high society of San Francisco’s Beth Israel Congregation, attending soiree after soiree in a wardrobe purchased solely on credit and bad checks. Before the two were to be wed, Bertha’s alleged son, Willie, asked Gruhn for $500 because he was unhappy with the idea of their union. Gruhn obliged. Willie also asked for many of Gruhn’s jewels, so that he could reset them in a modern way that Bertha would appreciate. Gruhn, again, obliged. And within the week, Bertha and Willie were gone, on their way to Los Angeles.

Gruhn turned to San Francisco’s captain of detectives to plead his case. Before he’d finished the story, the captain opened a book, flipped to photo Number 122, and asked, “Is this the woman?” Gruhn nodded in disbelief.

The detectives traced the pair to Texas, arrested them, acquitted Bertha, and found Willie guilty in a sensational trial in which the judge “could hardly force his way through the crowd” to reach the bench, according to an 1888 story in the Daily Alta California. As her story spread across San Francisco, Bertha was approached to do a one-woman show in which she recreated her scandals in an opera house, posing with flesh-colored tights. She often played scenes from Romeo and Juliet with an actor named Oofty Goofty who had made a name as a human punching bag. Due to Bertha’s size, Oofty sat on the balcony and she remained on the ground, according to the San Francisco Examiner. The show was a hit, and she soon went on tour across the West Coast, frequently engaging in wrestling bouts with any man who dared try her—and she generally knocked them out.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook