The Weird, Vain History of Who’s Who Books

From an early pet project to mockery and scams.

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

On an average day floating through the press release service PR Newswire, it’s inevitable that you run into a list of people who are designated as new members of a who’s who list.

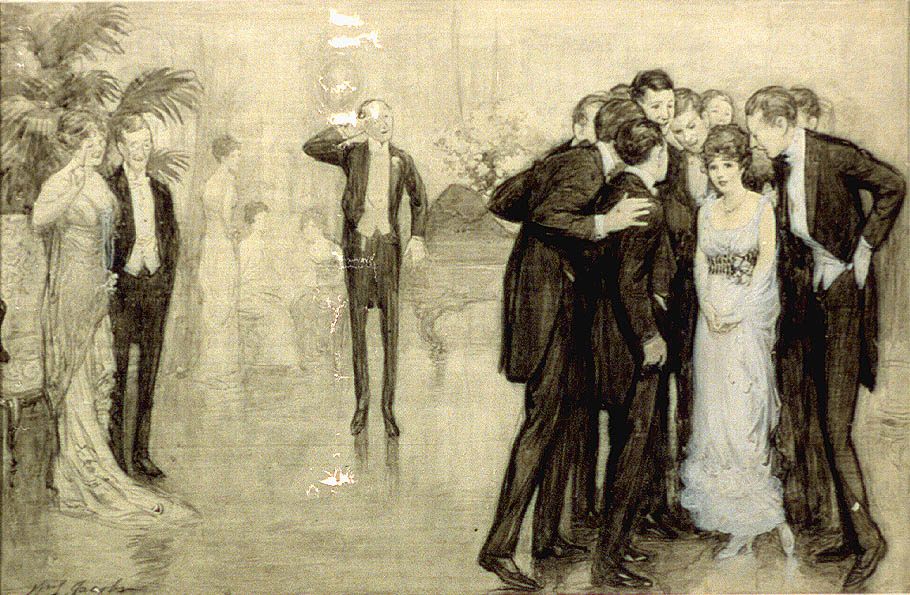

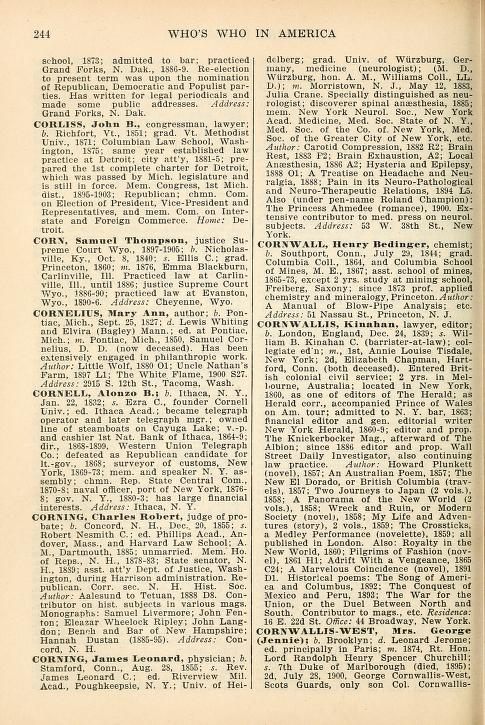

The list always varies but the intent is usually the same: To give a person notice for their life and career, no matter how seemingly mediocre. And while today they might just be a function of lazy p.r., there was a time, not too long ago, when who’s who lists were a more curated experience. In the United Kingdom, that amounted to a 250-page reference book that debuted in 1849 and is still published today, aspiring to be a compendium “of living noteworthy and influential individuals, from all walks of life, worldwide.” In the U.S., the first who’s who book was a little less expansive, the business-savvy project of an eccentric self-made publisher named Albert Nelson Marquis, who, in 1899, published a reference book for people who did notable enough things to get in a reference book for people who did notable things (though his choices tended reflect a conservative point of view.)

That book’s list of notables, already topping 8,000 in the first edition, included every member of Congress along with nearly every other politician during the era. But, as the Chicago Tribune reported in 1986, Marquis was noted for his odd standards of who actually got in. Traditional celebrities from film or sport were often looked over, for one, in favor of educators, clergymen, or other notables that reflected Marquis’s own personal interests. He also tended to make moral judgments, excluding Frank Lloyd Wright, for example, because of his turbulent personal life.

The fact that Marquis wanted to write the book at all was a bit of a surprise. An orphan, he was raised by his maternal grandparents in Ohio before moving to Chicago. Which is where, eventually, he launched his big idea.

Marquis’s grandparents ensured he received both a proper education and job experience in the family’s general store, but, as an adult, Marquis soon moved into publishing, launching his own firm in the 1870s at the age of 21. The company started in Cincinnati, but eventually moved to Chicago, where Marquis realized his dream: a first edition of Who’s Who in America, that made clear its intent in a prologue.

“Without claiming infallibility or inerrancy, it is believed that this publication will be a welcome addition to the list of handy helps that make up the library of indispensable books,” the prologue states. “Certainly nothing has been omitted that painstaking care, persistent effort, or expenditure of money could supply toward making the volume fully fill the purposes of its compilation.“

But, in the ensuing decades (the book endured long after Marquis died in 1943), the book was notoriously inconsistent—it wouldn’t take known criminals, for example—though Richard Nixon kept making the cut.

And the inconsistencies and gradually weakening standards of Who’s Who in America did not help the standing of the genre as a whole.

Take Donald Ray Grubbs, for example, an employee of a firm that analyzed the structural integrity of industrial sites, who was cited in a 1999 Forbes article as someone who had shown up in a wide variety of who’s who publications over the years, likely purchasing many of those items. (As it happens, the article was written by a reasonably big who: Tucker Carlson.)

“I have nothing but praise to say about them because I think they’re [doing] a good job,” the Texas man said then, perhaps with a wink.

Grubbs, though, was illustrative of publications that had fully moved from a watermark of notability to a way to self-submit autobiographies—which were rarely, if ever fact-checked.

The sheer number of who’s who books didn’t help, spawned by the fact that the phrase “who’s who” is not copyrighted, meaning that anyone who wanted to could launch their own.

All of which led to some books of a certain value, like 1967’s Who’s Who Among American High School Students, which publisher Paul Krouse released to combat the hippie image of American youth—and making some pretty broad assumptions in the process.

But Krouse’s book was one of hundreds, vastly cheapening the brand as whole—and leading to a lot of mockery, like a book called Who’s Nobody in America, a late-1970s attempt by a group of satirists to take on the ubiquity of the who’s who format.

“There’s something like 286 books beginning with the title, ‘Who’s Who in …’ Being in a ‘Who’s Who’ is only slightly more prestigious than being in the telephone directory,” co-author Derek Evans explained then.

Evans and his co-conspirator Dave Fulwiler later released a book that listed anyone who requested to be listed. Titled Who’s Nobody, the book went to print in 1981, a 111-page listing of nobodies. (It’s subtitle was, “Are You a Nobody? Can You Prove it?”)

A 1987 saga involving the humorist Joe Queenan might have solidified the declining reputation of who’s who for good. Queenan submitted a fictional person named R.C. Webster to Who’s Who in America; Webster, of course, got in, while Queenan got an essay about the matter for The New Republic. A sample:

Did anyone from “Who’s Who” ever contact Mr. Webster to check for authenticity? Yes, once he got a letter asking what year he’d gotten his master’s degree. At this point, I changed F&M T&A to Houston Polytechnical Institute, to see if anyone was paying attention. Nobody was.

Things only got worse after that, with who’s who gaining an eventual association with scammy offerings not unlike the Nigerian scam emails of the late 2000s.

“Most of the who’s who organizations are in it for the money with zero concern for to so-called honorees,” reporter Ben Rothke wrote in 2009 for the trade publication CSO.

Which brings us to 2017, and the question of who, exactly, who’s who is for these days, because, of course, you don’t need to show up in a vanity book to get exposure anymore. Social media accomplishes the same task for you just fine.

Still, it marches on. When I was wandering around the internet for this story, for example, I stumbled upon someone selling a .WhosWho top-level domain to suckers willing to pay for the privilege. According to 101Domain, it would cost me $4,125 to buy ernie.whoswho, though other domains on the service are a bit cheaper.

“Words have meanings, and .WhosWho not only conveys the message that you’re no Yahoo, but also very much the opposite,” the registrar states.

I might disagree.

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook