Why So Many Diners Look Like Train Cars

Often, they traveled by rail and were built that way too.

In the early 20th century, Americans were hungry for a quick bite. Yet long hours and late nights made going home to eat difficult. Through that, entrepreneurs saw an opportunity. It might come as a surprise to know that all aspiring restaurateurs had to do to fill this demand was to order a pre-made diner, modular and modern, often looking rather like a train car. It would even likely arrive by train.

Diners started out on wheels. In the late 19th century, street carts selling snacks and lunches had morphed into roving lunch wagons. While some lunch wagons sported Gilded-Age decor, such as elaborate coffee urns and etched windows, many were ramshackle, giving them an iffy reputation.

The person credited for creating the polished diner image was a lunch wagon manufacturer named Patrick Tierney, whose prefabricated and eventually stationary eateries featured tiled floors and a revolutionary indoor restroom. Meanwhile, on the rails, dining cars were setting the standard for food service on the move. Train historian Joe Welsh describes “a traditional [dining car]” as consisting of a “long ‘tunnel’ of tables and chairs.” Tiny lunch wagons couldn’t accommodate the demand for fast, tasty meals. So manufacturers began building shippable, train-like “dining cars,” which people had shortened to “diners” by the mid-1920s.

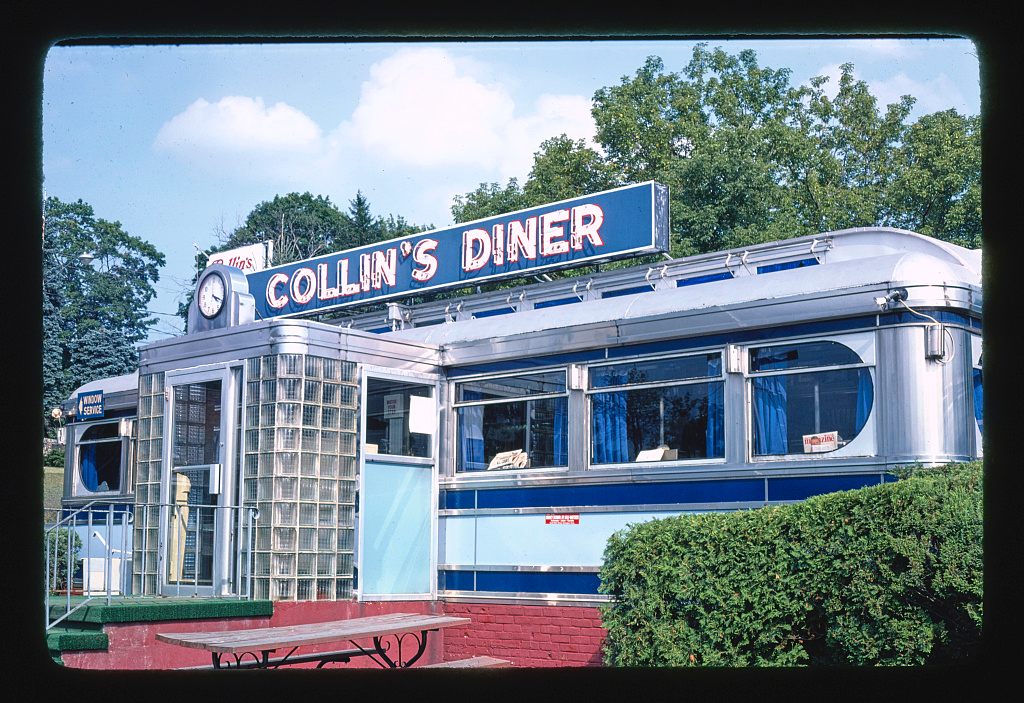

As with train cars, diners were manufactured with mobility in mind. Trains took on a chrome, streamlined look in the 1930s, epitomized by the glorious design of the 1934 Burlington Zephyr train. Diners followed suit. Roland Stickey, a New York inventor and designer, dreamed up the Sterling Streamliner diner model for the J.B. Judkins Company of Massachusetts. It looked so much like a train that “[only] the tracks and the passenger cars were missing,” writes roadside culture historian Michael Karl Witzel. With it convenient shape and cutting-edge look, similar designs soon were shipped across the country, a culmination of what Witzel calls the diner’s “strange alliance with trains.” Often, they were built in New Jersey: Today, the state has 600 diners in operation, and is still considered America’s diner capital.

Shipping diners happened either by truck or train, which understandably limited diner design. “For example, all diners shipped to Florida went by rail,” writes diner expert Richard Gutman. For years, they could only be shipped in one piece, limiting their size and how many seats could fit inside. In the 1940s, the Paramount diner manufacturer finally devised a way of building a diner that could be shipped in pieces and built without compromising structural integrity, freeing diners from their restricted, dining-car shapes. One example is the now-abandoned Comet Diner in Hartford, Connecticut.*

Many still-existing diners retain long, train-like shapes. Though the vast majority of classic diners were prefabricated, a handful were even made out of old train and trolley cars, since they fit so well the pre-conceived idea of a diner’s structure. While diner design is no longer limited by what can fit atop a train track, these train-inspired diners continue to serve up breakfast and burgers for hungry people on the go.

*Correction: This story previously stated that the Comet Diner in Hartford, Connecticut, was built by Paramount as a two-story diner. However, the lower level was not built by Paramount.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook