Why the King Owns All the Swans in England

Only wealthy landowners were allowed to feast on these royal fowl.

Swans, according to those who have eaten them, are tasty birds. The meat is “more like duck than it is like goose,” one hunter reports; it’s “lean, lightly gamey, moist, and succulent,” in the words of a chef.

Today, it’s rare for swan to be served, but for hundreds of years in England, eating swan was a mark of status. No one could own or eat one without paying the monarchy for the privilege, and an elaborate system of marks developed to track swan rights. By default, though, the king or queen owned the country’s swans, and that’s still true: Any unmarked swans swimming in the open waters of England belong to the king.

Rules governing swan ownership in England date back before the mid-13th century, as Arthur MacGregor of Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum explains in a 1995 issue of Anthropozoologica. By 1361, the crown had an official Royal Swan-herd, and by 1463 there was a “Swan-mote” with commissioners appointed to hear swan disputes.

Swans were considered royal fowl, but by the beginning of the 15th century, wealthy people could buy the right to own, sell, and eat them. If you wanted to keep swans on your property (a right reserved for those who had property to begin with), you had to buy an expensive “swan mark” from the king, which you’d carve or brand into the beaks of your swans.

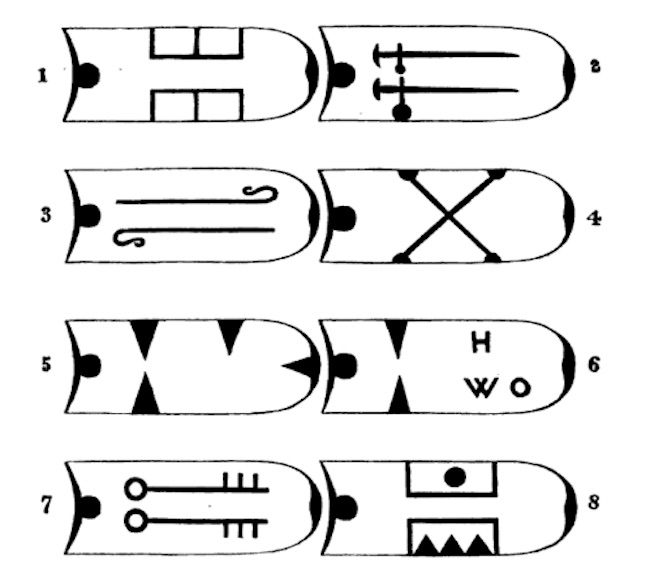

These marks, one of the oldest propriety marks in England, might have started as simple lines and shapes, but eventually there were hundreds of swan marks in England and whole books dedicated to keeping track of them. They were designed to look like swords or crossbows, heraldic symbols, and eventually letters. Every year swan-masters would row through open waters, determining the ownership of cygnets and marking them. Any unmarked birds belonged to the crown.

This “highly structured system of ownership,” writes MacGregor, seems to be “an English peculiarity.” (It didn’t even extend to Scotland.) It lasted for centuries, though, and put in place measures that protected the swan population. It was illegal, for instance, to steal swan eggs or to cut the grass or reeds within 40 feet of a swan’s nest.

By the 18th century, swan had fallen out of a favor as a status meat. Some people continued to mark their swan’s beaks until in the late 19th century, when animal cruelty activists argued it constituted “unnecessary suffering” and Queen Alexandra, the wife of King Edward VII, stopped the royal birds from being marked.

This tradition of royal swan ownership carries on today, though: The king still owns every unmarked mute swan—the white-feathered bird with a knob on its orange beak, the bird that you most likely think of when you think “swan”—on England’s open waters.

Killing swans was outlawed in the 1980s, when the population in England was shrinking, and many people now believe that only the king is allowed to eat mute swans. That’s not exactly correct, but since he’s considered immune from prosecution, if he had a hankering for swan at Christmas, a traditional dish, no one could stop him from acting on it.

Update 4/21/2023: This story has been updated to reflect King Charles III’s ownership of England’s swans.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook