The Brief, Wondrous, High-Flying Era of Zeppelin Dining

The Hindenburg’s fattened ducklings and caviar were essentially German propaganda.

It might not have been the best food on Earth, but it had a legitimate claim to being the finest fare in the sky. On board a zeppelin, one of the German-owned rigid airships that traversed the Atlantic in the early 20th century, travelers ate like kings—or, at the very least, lesser nobility. From 1928 to 1937, when the Hindenburg disaster saw the once-bright future of lighter-than-air travel go up in smoke, passengers experienced food to rival modern luxury cruise ships. These rigid airships were enormous structures, the size of buildings, hanging more than 1,000 feet in the air and cruising at speeds exceeding 80 miles an hour.

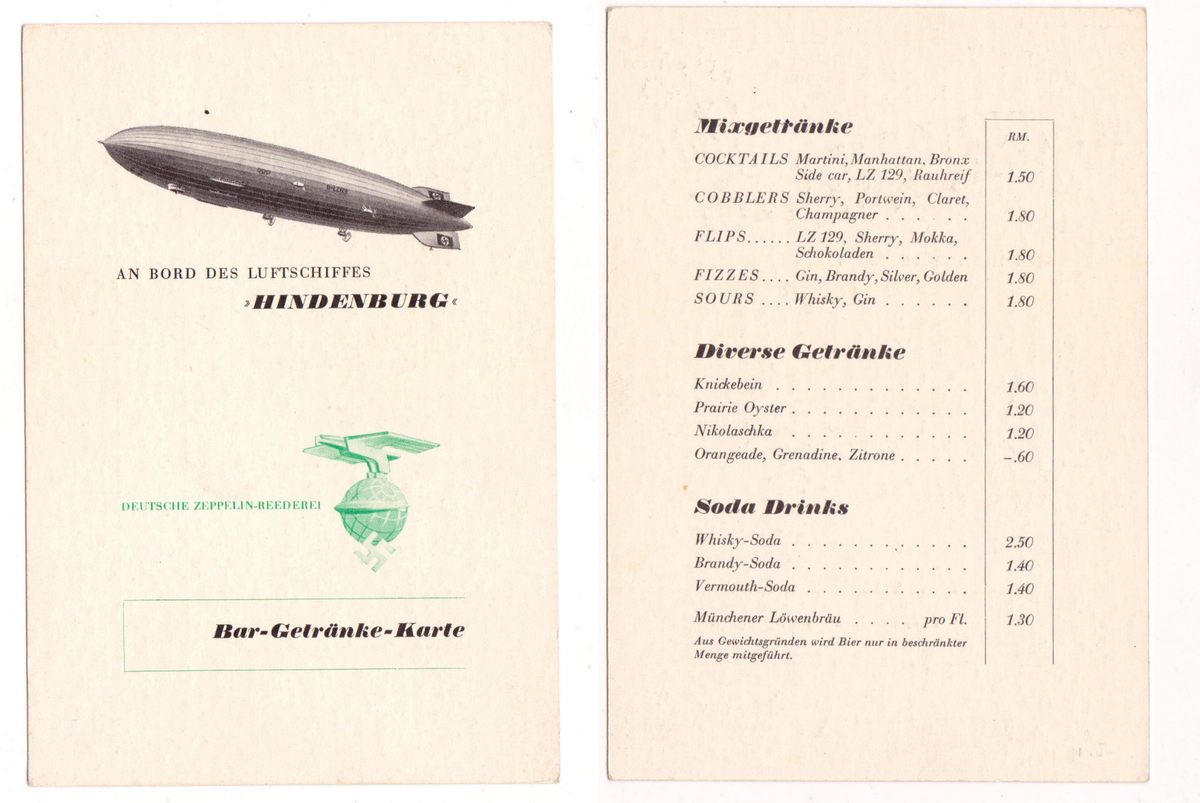

Airships went farther and faster than anyone ever had before, but journeys were still rather time-consuming. A trip from Brazil to Europe, for instance, took three days, and there was little to do except look out the window, read, socialize, eat, and drink. These last two, as one might expect, were taken quite seriously. Meals were regular and lavish, and drinking so excessive that prairie oysters, a hangover cure made with hot sauce and a whole raw egg, were listed below the cocktails on the bar menu.

Food aboard the Graf Zeppelin, and its sister ship, the Hindenburg, was based on the dining one might find at a traditional, high-end European hotel. The chef on the final Hindenburg trip, Xaver Maier, for instance, had come to it from the Ritz, in Paris. Because of that, the food was not always to American tastes, says Dan Grossman, airship historian and author of Zeppelin Hindenburg: An Illustrated History. “The most important thing to remember about food on the Hindenburg was that it was German food—very, very German food. There were some complaints from primarily American passengers,” he says, “that it was a lot too heavy and specific for their tastes.” Menus were strong on meat. Vegetables, where they appeared, were usually lathered in butter or a rich cream sauce. “The food was not really tailored to the needs of their customers.”

The libations were also very German. On the Hindenburg’s maiden flight, the bar is said to have run out of gin. This is because, says Grossman, “Germans don’t drink a lot of gin. Brits and Americans drink tons of gin, but the very fact that they did [run out] shows that they weren’t really thinking about accommodating the expectations of their passengers.” An inventive guest, Pauline Charteris, who was married to the author Leslie Charteris (creator of “The Saint”), is said to have taken kirsch (a cherry brandy), dry vermouth, and grenadine to produce an alternative “Kirsch Martini.” Later that night, she entertained guests by singing a contemporary jazz song, with the lyrics “Mamma don’t want no gin, because it makes her sin.”

Zeppelins flew so much lower than modern planes do that they did not have the same cold, dry, pressurized cabin air that dulls taste and smell today. Airship food would therefore have been much more flavorful than what we eat aloft today—even if the menu didn’t include fattened duckling with champagne cabbage. No expense was spared. In The Great Dirigibles: Their Triumphs and Disasters, John Toland describes the Hindenburg’s larder: “turkeys, live lobsters, gallons of ice-cream, crates of all kinds of fruits, cases of American whiskey, and hundreds of bottles of German beer.” The Graf Zeppelin allowed for 7.5 pounds of “victuals” per passenger, per day, whether fresh or in specially prepared cans, with labels hand-affixed by the chef’s sister.

The emphasis on German cuisine was no accident. While there was a hope that these commercial zeppelin flights would one day be profitable, they were primarily a way to demonstrate a kind of German cultural strength, says historian and writer Richard Foss, author of Food in the Air and Space: The Surprising History of Food and Drink in the Skies. “It was an instrument of national prestige. It showed a Germany that had been so completely trampled in the war [World War I] now had the fastest and most luxurious method of transport. They could serve caviar with every meal, they could do whatever they wanted to, because they didn’t really have to make money.” Joseph Goebbels, who ran the Ministry of Propaganda, invested in the company for its ability to represent Germany on the world stage.

The day’s eating began sometime around 8 a.m. Tables were laid with vases of fresh flowers and blue-and-white china. Despite the weight considerations always associated with air travel, the plates and teapots were inlaid with real gold, and were very heavy. Upon arrival on the ship, passengers were given a single white napkin, in a personalized envelope. They were to keep this and reuse it for the rest of the journey to keep weight down—though it’s hard to see how much of a difference this made on the 236-ton, china-laden Hindenburg.

The Hindenburg’s dining room was furnished with lightweight, state-of-the-art aluminum Bauhaus furniture. Measuring 46 feet in length, the space could accommodate all guests on board simultaneously, at either separate tables or one long one. “They did everything they could do to make it feel like a land-based restaurant,” says Foss. On the final Hindenburg voyage, guests were served the following traditional German breakfast:

Coffee, Tea Milk, Cocoa

Bread, Butter, Honey, Preserves

Eggs, boiled or in cup

Frankfort Sausage

Ham, Salami

Cheese

Fruit

At the time, cocoa was believed to be a health food of sorts that aided in digestion and strengthened the constitution. Every morning, bread rolls were baked fresh in the all-electric, all-aluminum kitchen, which had been designed both to limit weight and minimize the risk of a catastrophic kitchen fire. It was, after all, basically inside a building full of flammable hydrogen.

Guests spent a considerable amount of time in the bar, the only place on board where they could smoke. There, they had access to as many as 15 different kinds of wine and sparkling wine, as well as a selection of mixed drinks, divided into “Sours,” “Flips,” “Fizzes,” “Cobblers,” and “Cocktails.” In addition to the most common cocktail orders, the bar offered a few specialties: LZ 129, made with gin and orange juice, and Maybach 12, the formula for which is now lost. “We don’t really have recipes [for their cocktails or meals]—in fact, things were really nonstandard,” says Grossman. “It was very much run on an apprenticeship basis. People knew their jobs because they’d been doing them for a really long time.”

Also set up in the bar was the world’s first aluminum alloy piano. Weighing just 356 lbs, it was made of duralumin, an alloy of aluminum, copper, and other metals, with hollow tubing for its legs, back bracing, and lyre. The outside was covered in light-colored pigskin leather. It had been taken out of the airship before the 1937 travel season, so it avoided the fate of the rest of the Hindenburg disaster, though it was accidentally destroyed several years later, during World War II.

By the time of the Hindenburg disaster, nearly 3,000 people had ridden on the luxury airship, then the global standard for speed, luxury, and fine dining. Today, it’s near-impossible to eat food of any kind on any sort of dirigible. Until recently, the Hendricks blimp, which is currently out of action, served three gin-based cocktails in the air—but it’s a far cry from the golden age of dirigible dining.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook