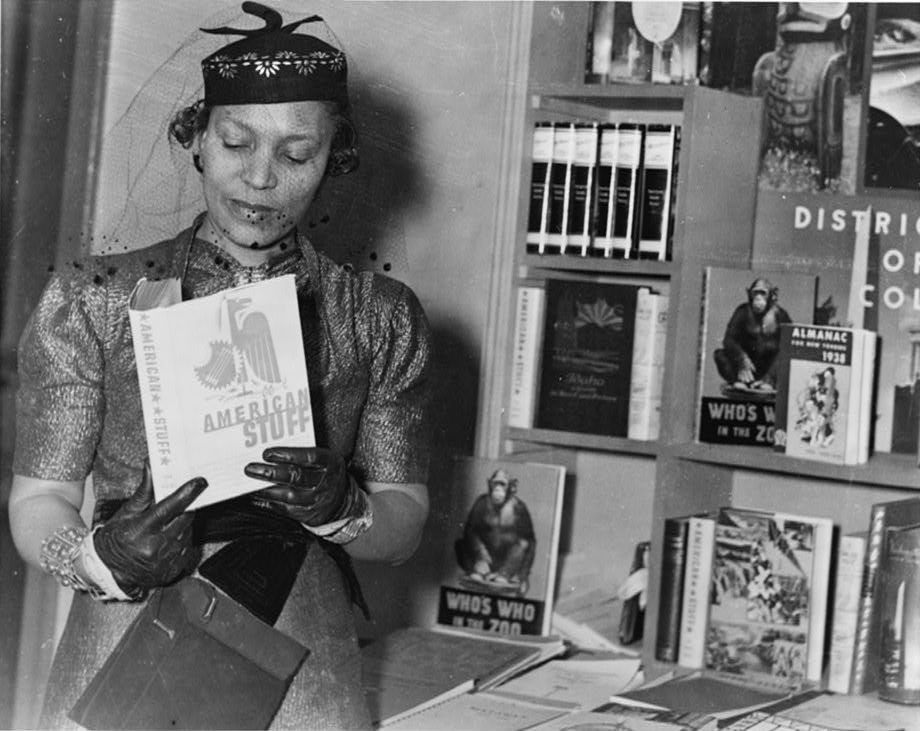

An Unpublished Work by Zora Neale Hurston Is Set for Release in 2018

“Barracoon” tells the story of the last known survivor of the Atlantic slave trade.

In 1973, writer Alice Walker flew to Florida to find Zora Neale Hurston’s grave. Hurston, an anthropologist and writer of four novels and over 50 short stories, plays, essays, and folklore histories—perhaps most notably 1937’s Their Eyes Were Watching God—had been buried in an unmarked grave 13 years earlier. Overgrown, forgotten, hidden, the final resting place of the literary giant lay out of sight and out of the public consciousness.

Walker’s mission was to find the grave and mark it and remember Hurston for what she was: an important voice in the American literary canon.

Today, thanks to Walker’s quest, Hurston’s grave is marked. A large stone that reads, in part, “A genius of the south. Novelist, folklorist, anthropologist” marks her final resting place now. Walker’s quest revitalized the author’s popularity, and now her books are on shelves and in classrooms all over the United States.

Now there’s another opportunity to uncover and remember Hurston’s legacy, just like Walker did all those years ago. HarperCollins is publishing a new Hurston book, called Barracoon, in May 2018.

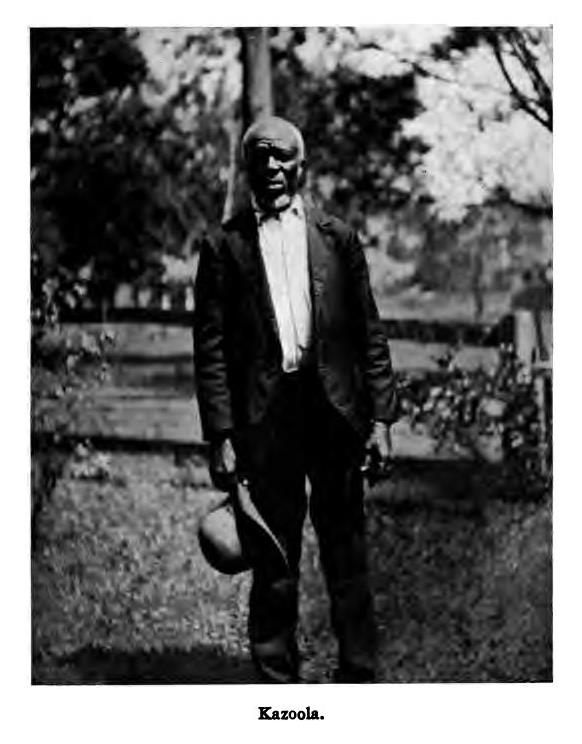

According to the publisher, the book is “the true story of the last known survivor of the Atlantic slave trade—illegally smuggled from Africa on the last ‘Black Cargo’ ship to arrive in the United States.” Hurston based the book on interviews she conducted in 1927, and again in 1931 with Cudjo Lewis, a 95-year-old man from Plateau, Alabama who was the last survivor of the slave trade—the last who could remember the journey on the ship the Clotilde, where he and over 100 other people endured the Middle Passage in 1859.

A 2010 excavation in Plateau, where many of the former slaves settled, unearthed some artifacts—jewelry, crockery, glass fragments—that gave some insight to the way Clotilde survivors and their descendants may have lived. And now, with the publication of Hurston’s book, we will have their words to help paint a fuller picture of their lives.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook