AO Edited

Cimetiere de Picpus

The headless bodies of more than 1,300 guillotined victims of the Reign of Terror are buried here in mass graves.

Heads were rolling in Paris in the summer of 1794, and when you have that many bodies baking in the sun you need a convenient and quick place to dump them. Luckily for the revolutionaries operating the guillotine at Place de la Nation (then known as Place du Trône, and as the Place du Trône-Renversé during the Revolution), a convent with a pit-friendly garden was located just a few minutes wheelbarrow ride away.

In June 1793, the French Revolution dissolved into chaos. King Louis XVI had been executed in December of 1792, leaving behind an absence of clear government, followed by food shortages and riots, and a backlash against the revolutionaries. The suppression of complaints came in the form of a year and a half of “La Terreur” (Reign of Terror) launched under Maximilien Robespierre, and saw the execution of an estimated 16,000-40,000 “enemies of the revolution.” Guillotines were set up in major plazas, hosting as many as 55 executions in a day.

By June and July of the following year, the revolutionaries had run out of viable burial space in the normal locations, and they began looking for new real estate within the crowded center of Paris.

The convent of the Chanoinesses de Saint-Augustin had been converted into a prison hospital in March of that year. In June, the garden was dug up to accommodate mass graves for approximately 1,300 men and women. Among the dead buried at the cemetery are sixteen Carmelite nuns known as the “Martyrs of Compiègne” who famously proceeded to their death singing hymns and were beatified by the Catholic church in 1906. Their story is memorialized books as well as in the opera Dialogues of the Carmelites by Francis Poulenc, which includes the sound of the dropping guillotine blade in the score.

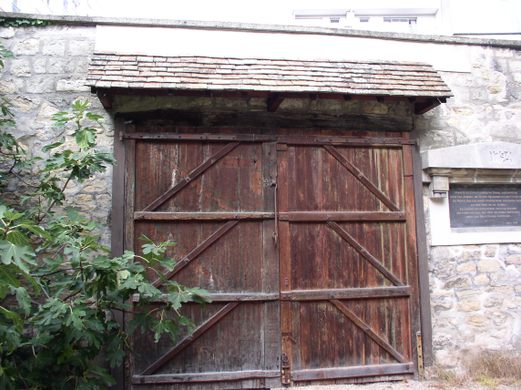

A plaque on the cemetery wall which reads “servit les muses, aima la sagesse, mourut pour la vérité” (“served the muses, loved wisdom, and died for the truth”) honors the poet André Chénier, one of the last to be executed on orders from Robespierre.

On the 28th of July, Robespierre was himself guillotined at the Place de la Révolution. Fittingly, he was buried with others executed with him in another common grave (the Cimetière des Errancis, now gone). After the Revolution, the remains at Errancis were moved to the Paris Catacombs, its place marked by a simple plaque at No. 22, boulevard de Courcelles.

An American flag marks the post-Revolutionary grave of the Marquis de Lafayette, a Frenchman who fought in the American Revolutionary War under George Washington. In the French Revolution he was part of the National Assembly, and drafted the Déclaration des droits de l’Homme et du Citoyen (Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen), France’s equivalent to the American Bill of Rights. He outlived both Revolutions (just barely), and went on to travel widely as a statesman. He died of pneumonia in 1834, and was buried at the Cimetière de Picpus under soil from Bunker Hill in Boston.

Today, the Cimetière de Picpus is the largest private cemetery in Paris. It is remarkable not only for its grisly history, but also for the fact that men and women, adults and children, commoners and aristocrats all reside in the same grave. Their names are recorded on the walls of the convent chapel.

Know Before You Go

The nearest Paris metro stations are Nation and Picpus. The cemetery has separate summer ( 2 p.m. to 6 p.m.) and winter (2 p.m. to 4 p.m.) hours, and is open Monday through Saturday. Admission is 2 euros a person. The best metro is Picpus.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook