AO Edited

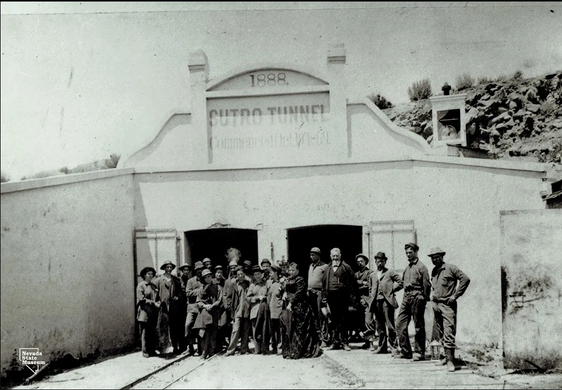

Sutro Tunnel

This colossal underground passage paved the way for large-scale drainage and access tunnels across the U.S., but it almost wasn’t built.

In the late 19th century, the tireless efforts of a Prussian immigrant and entrepreneur led to one of the most ambitious engineering projects of its time.

Adolph Sutro came up with the idea to build a drainage tunnel connected to the Comstock Lode, the first major discovery of silver ore in the United States. Not only would the underground tunnel improve safety conditions for miners—who were faced with the possibility of underground flooding, as well as inadequate pumping systems—but it would also allow for deeper mine access within Nevada’s high desert terrain.

Sutro, who later spent his Comstock billions on building San Francisco’s Cliff House and Sutro Baths, knew that having to physically pump out any flood water from the area’s deep mines would cost a fortune. So instead, he proposed a tunnel that would run under the Comstock Lode from the lowest possible point beneath Virginia City to an exit point near Dayton—a nearly four-mile distance—where water could drain out into the valley. Such a feat of engineering would reduce transportation costs, while simultaneously ventilating the mines and protecting miners’ lives in the process.

But not everyone was onboard with Sutro’s plan, including mine owners who were worried that the entrepreneur would try and take away their mineral rights if he connected the tunnel to their claims. So to help fund his endeavor, Sutro established Sutro Tunnel Company, selling stock certificates to bring in money for its construction, and collecting capital from miners who desired a higher level of work safety.

The fundraising was a constant hustle. However, when a deadly fire broke out in Nevada’s Yellow Jacket Mine in 1869, costing the lives of at least 35 miners who were trapped within its shafts, Sutro’s idea gained a lot more support. Many believed that a tunnel could have helped save those who perished.

Construction on Sutro’s tunnel began later that same year. Nearly a decade later, it was finally complete. On September 1, 1878, the tunnel crew reached the Savage Mine in Virginia City, creating a 10-by-12-foot-wide drainage system that stretched 3.88 miles (20,489 feet) to Dayton. Not only did it work, but it also led to the creation of large drainage and access tunnels elsewhere in the U.S., including several in Colorado, such as the Argo Tunnel at Idaho Springs.

Soon after this underground pipeline began operating, Sutro sold a majority of his shares and moved back to San Francisco. Still, he stayed on as a tunnel board member and put his younger brother Theodore Sutro in charge of the day-to-day business.

In 1894, Theodore Sutro sold the tunnel to a man named Franklin Leonard Sr., who operated it until World War II. When the U.S. Government’s War Production Board issued executive order L-208, shutting down “nonessential” mines to free up resources for the war effort, Sutro Tunnel closed.

Today, the remnants of this remarkable piece of ingenuity is undergoing restoration thanks to the Friends of Sutro Tunnel, a non-profit that’s working to preserve the tunnel’s history and integrity, and also make it safe and accessible for visitors.

Know Before You Go

The Friends of Sutro Tunnel hosts guided tours of the newly-rebuilt, first 50-feet of Sutro Tunnel, along with 11 historic buildings surrounding its entrance, typically twice a month during spring and summer. Each tour shares the history of Adolph Sutro and how his pioneering tunnel came to fruition. Visit their website for more information. Tickets are $65/per person (funds go towards the tunnel’s upkeep).

The non-profit also hosts a series of special events, including paranormal investigations at the site, and Virginia & Truckee Railroad train excursions to benefit the Sutro Tunnel restoration efforts.

This post is sponsored by Travel Nevada. Head here to get started on your adventure.

Plan Your Trip

The Atlas Obscura Podcast is Back!

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook