A Short History of Rakes, and Why You Should Think Twice About Using Them

They’ve evolved through the years.

But what do you do with leaves once they’re on the ground? (Photo: Cristian Bortes/CC BY 2.0)

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

People are unhealthily obsessed with mowing their lawns, despite the fact that the popularity of doing so only goes back about a century or two.

But as seasons change, the mindset that leads people to freak out about their lawns stays the same—but the target changes.

Odds are that if you live in a state north of the Mason-Dixon line, you’ve probably seen a dead leaf or two on the dirty ground.

Some people will naturally be attracted to raking those leaves into a huge pile, but the National Wildlife Federation has a really crazy idea: They say you should just leave those leaves where Mother Nature decided to leave them. Should we just leave leaves grounded?

Well, that’s what The Farmers’ Almanac recommends—they say leaves make really awesome compost. The 1844 edition of the almanac put it as such:

Prepare compost for a new year, by raking dead leaves, soil, sand, &c. in a heap, to turn over occasionally. Pour in brine, soap-suds, &c. from the house into it. Transplant still hardy kinds of flowering shrubs, suckers, &c. Clear the boarders from dead annuals, leaves, stumps, &c.; shelter the choice bulbs and double flowering plants.

(By the way, curious grammar nerds: “&c” is another way of saying “et cetera” during an era when book space was a luxury.)

The advice the almanac offers today, though written a bit different, is essentially the same.

“Pound for pound, leaves contain twice the mineral content of manure,” writes Robin Sweetser, The Farmer’s Almanac’s gardening blogger (it’s so weird to say that!). “The huge amount of organic matter they offer can be used to improve soil structure. Leaf humus can lighten heavy clay soils and increase the moisture retention of dry sandy soils. No organic gardener should pass up this opportunity for a free soil amendment.”

Zhu Bajie from Journey to the West. (Photo: Public Domain)

That seems like a good argument for keeping the leaves on the ground. But trees lose a lot of leaves—roughly 3,600 pounds in a tree’s lifetime and 200,000 total leaves in a 60-year period, according to the Wisconsin County Forests Association.

While most of those leaves put nutrients back into the ground, the truth is that some people love raking, and for those who find the process enjoyable, it turns out that the rake has a lot of history.

If National Wildlife Federation President and CEO Collin O’Mara found himself face-to-face with Zhu Bajie, it’s entirely possible that his organization might change its mind about raking—out of fear.

See, Zhu Bajie, one of the major characters in the 16th-century Chinese novel Journey to the West, is famous for carrying a massive, extremely heavy rake that he uses as a weapon. The heavy iron rake—best known as the jiǔchǐ-dīngpá, or nine-tooth rake—is often used in the story to kill demons, who when defeated have nine teeth-marks on their flesh from the weapon. Sounds like a rake you don’t want to mess with.

“No other blade is worth a mention besides my rake, the sharpest weapon ever,” Zhu says at one point in the novel.

(On the other hand, Zhu Bajie is something of a goof who largely serves as comic relief for the plot, so maybe O’Mara has no reason to worry about this man-pig!)

As you can imagine from this description, the rake is not a relatively new invention, unlike the lawn mower. Rakes have been around a long time, and while they’re mostly associated with keeping lawns and gardens in tip-top shape. They’re rarely (but sometimes) used as weapons, but often treated as annoyances in pop culture.

(If you ask me, they’re also annoyances in real life.)

Traditionally made of materials such as bamboo and metal, the tale of the garden rake is one of slow evolution, one that can best be seen by spending a half an hour walking through old patents on Google. But you don’t probably have half an hour, so let’s go through some of the highlights:

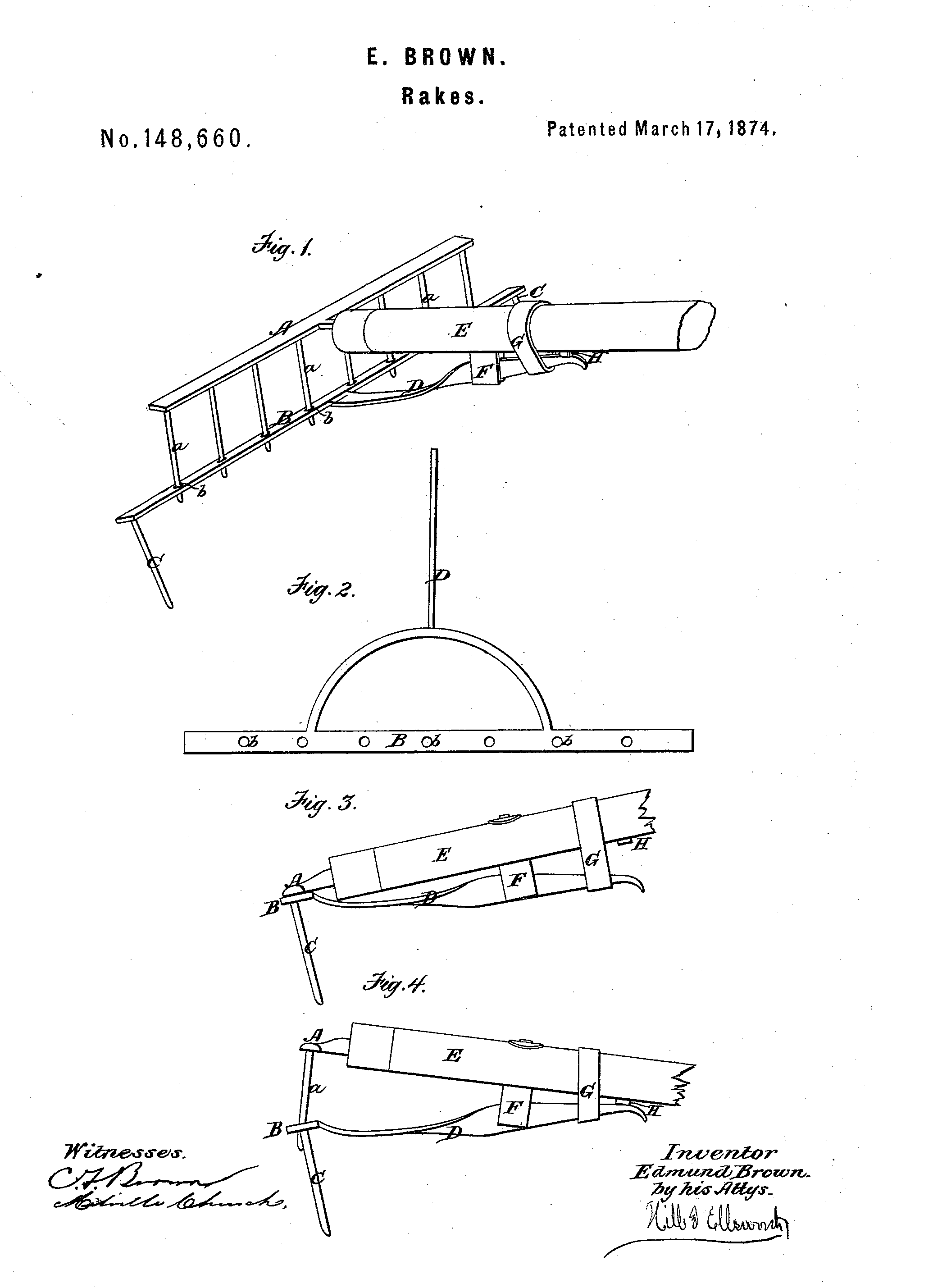

The earliest example of a rake patent, dating from 1874. (Photo: Google Patents US148660A)

Here’s the earliest example of a garden rake shown in the U.S. patent system, dating back to 1874. The device includes what its creator, Edmund Brown, describes as “an automatically clearing attachment for iron tooth door-yard rakes, which shall remove all matter that may be collected between the teeth by simply raising the rake from the ground” in the patent document.

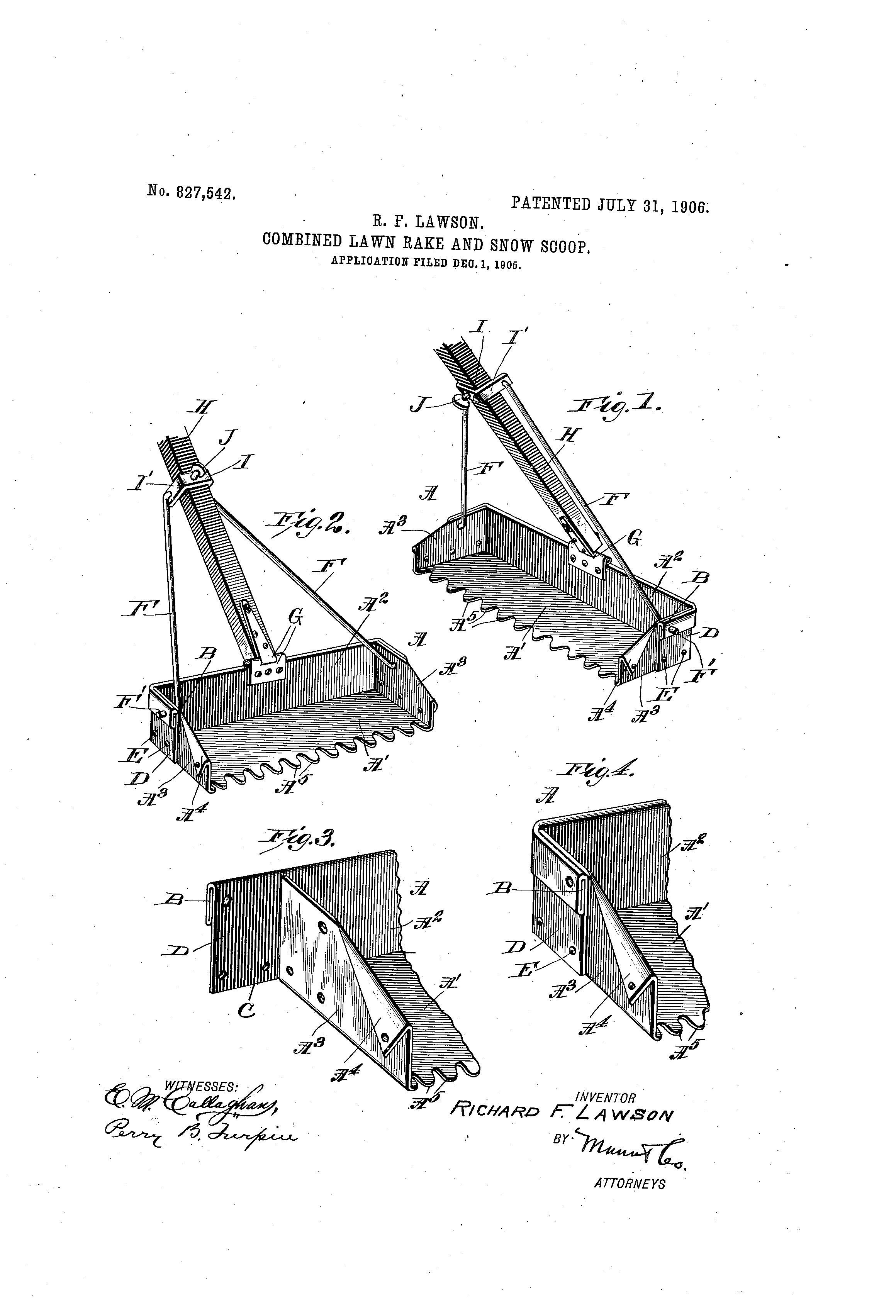

Ideas were slowly but surely evolving. This 1905 invention by Richard Franklin Lawson effectively combines the best elements of the snow shovel and the rake into a single device. To be totally unfair to him, it doesn’t look like it’s very good at either shoveling or raking, so it’d be time for him to go back to the drawing board if we weren’t talking about something he did 110 years ago; we’re pretty sure that he’s dead at this juncture.

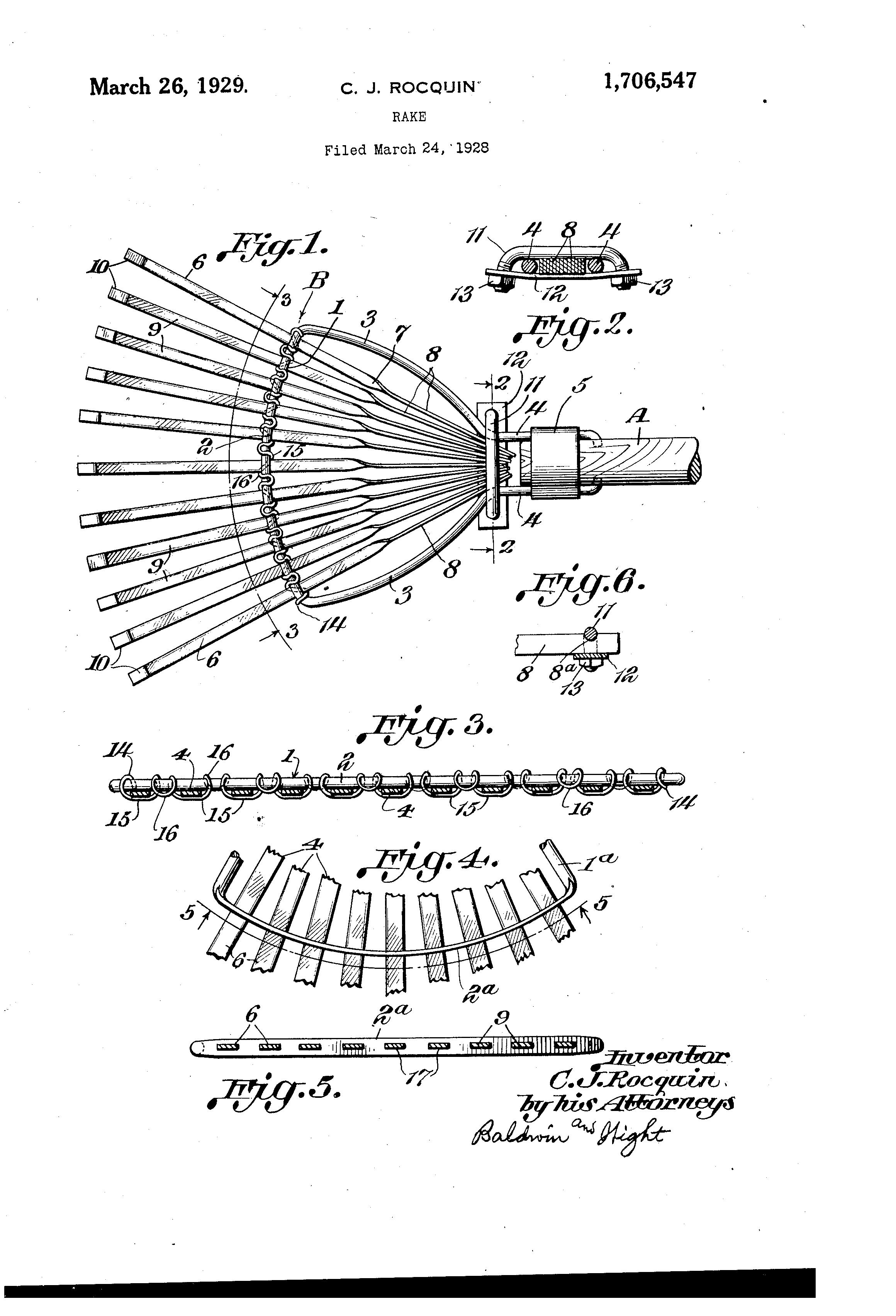

The turning point in modern rake design may be thanks to the unsung hero and serial patenter Camille J. Rocquin. The New Orleans-based inventor held patents for at least five different kinds of rakes. Rocquin’s rake designs—particularly the 1929 variation shown above—are similar to what you’d find in stores today if you were shopping for a metal rake.

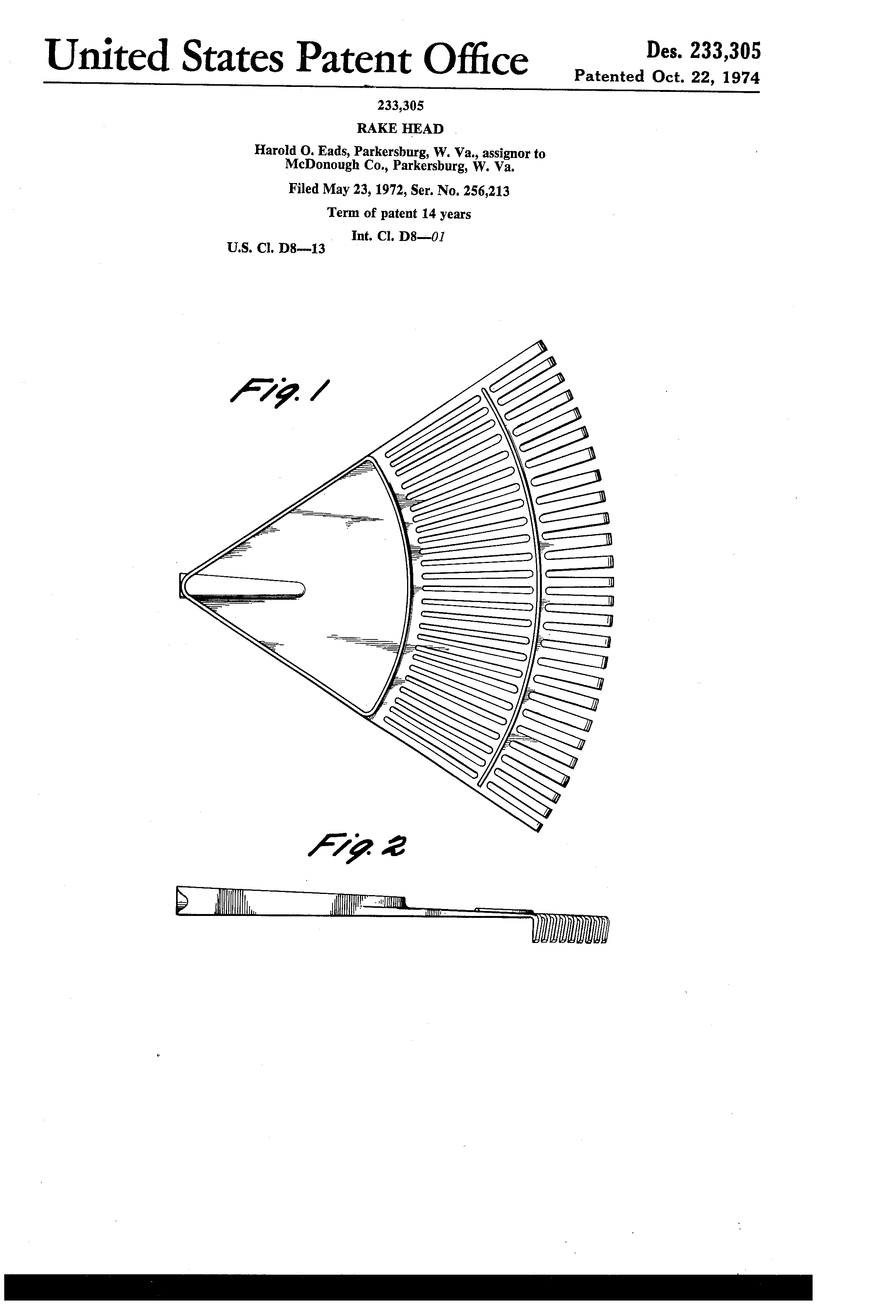

The type of rake you’re probably most familiar with, the molded plastic rake, didn’t come about until the 1970s in its current shape. It was created by an inventor named Harold Eads, who worked for the Ames company—pretty much the biggest name in rakes. “An object of the present invention is to provide a rake which has all of the advantages of both steel tine rakes and bamboo rakes, without the disadvantages thereof,” the 1972 patent document states. Considering we generally use plastic rakes nowadays, it appears that that objective was reached.

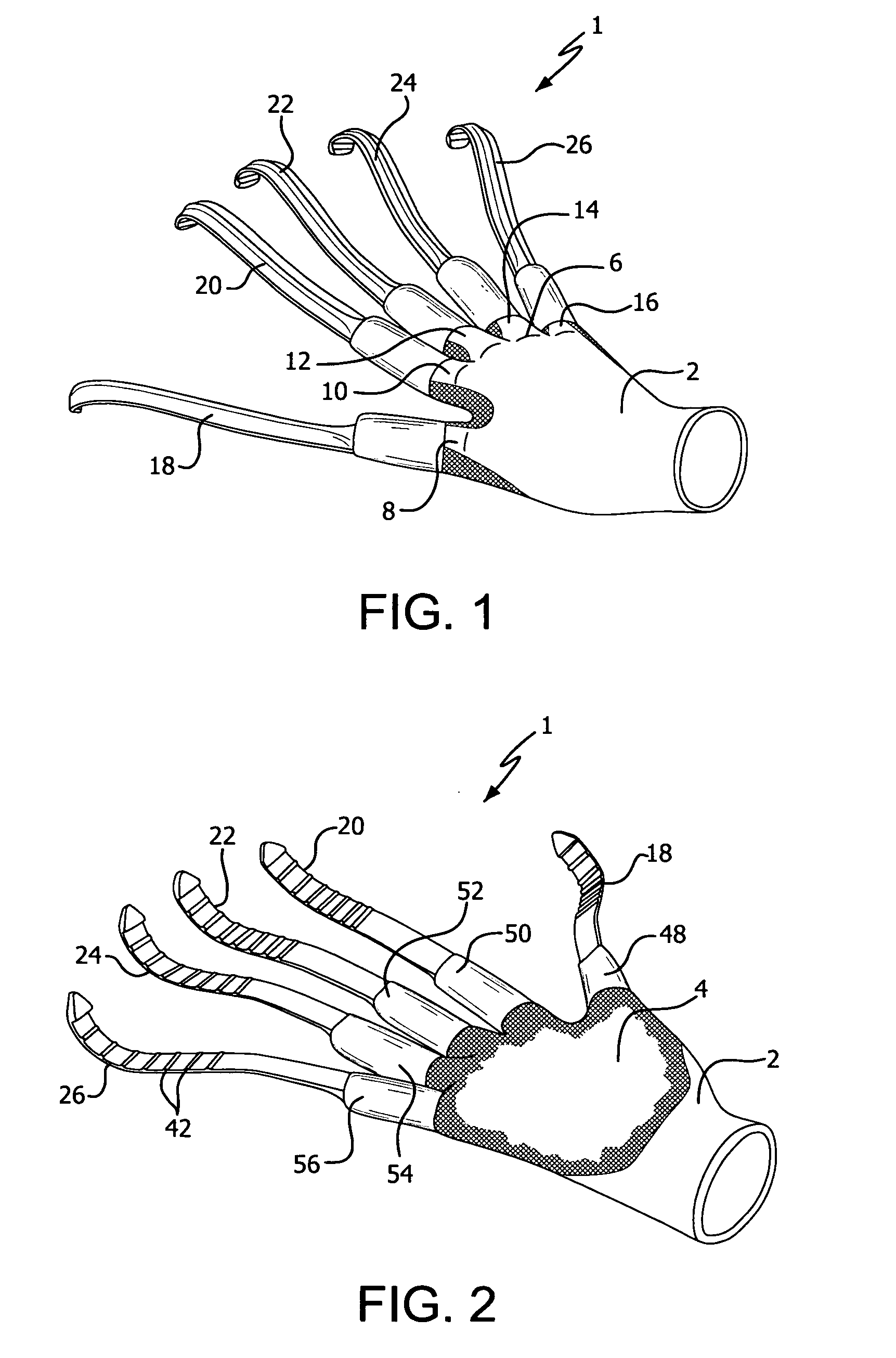

Not a prop from Nightmare on Elm Street, but the 2011 patent for a glove rake. (Photo: Google Patents US201203)

Honestly, we just put this glove rake patent in, despite the fact it only dates back to 2011, because we think it’s hilarious. “It is the object of the present invention to provide a glove rake which truly acts as an extension of the wearer’s hand, allowing the wearer to separately and independently rotate each of the fingers of the glove rake to perform a variety of different gardening, landscaping, and yard work tasks with maximum efficiency,” the patent states. Like we said, hilarious.

One of the most interesting tales I discovered when I wrote about hand dryers last year was that of Oregon State Senator Chris Edwards, who led a lonely campaign to limit the amount of noise a hand dryer can emit.

Edwards had a strong personal reason for this—his son, who is autistic, couldn’t handle the loud noise of the more powerful hand dryers, which is incredibly common in public places.

It makes sense that there are at least some people bugged by the noise of the hand dryers—and it’s a frustration that translates to leaf blowers, which operate at roughly the same decibel level, between about 70 and 90db based on the model for both kinds of products. But since people tend to use leaf blowers in the open air and for longer periods, the frustration about hearing the blowing noise tends to cause a lot more problems in local communities.

And people are passionate about this stuff, especially when it comes to homeowners associations.

Just last fall, for example, a Georgia man was fined and threatened with jail time for reportedly overusing his leaf blower. He was told by a judge that he could only use his leaf blower over three 30-minute periods per week. He fought the fine, but lost.

(Photo: Dean Hochman/CC BY 2.0)

“I walked away going, ‘what country are we in that they could put me in jail?’” Kim Treaster said.

In some corners of the internet, jail time is the least they’d do to Treaster. Just as an example, there’s a website called “Nationwide Leaf Blower Ban,” which describes leaf blowers as “horrific death devices.” The anonymous author is so passionate about this issue that he runs five other sites which are described as anti-leafblower.

And some, such as Alternet writer Cliff Weathers, describe leaf blowers as a public health nuisance that drives people mad and puts a homeowner’s trash into someone else’s street.

“So, it’s a zero-sum game, giving the home or business owner a pristine driveway or lawn, while the dirt and debris has just been moved elsewhere in the neighborhood. That’s not cleaning—it’s one residence making its mess the community’s problem,” Weathers wrote in 2014.

On the plus side, leaf blowers are starting to get a little quieter—which should help you earn some friends at the next HOA meeting. Consumer Reports has a list of some of the least annoying leaf blowers, such as the Echo PB-250LN Handheld Gas Blower, whose volume tops out at a relatively quiet 65 dB.

Clearing leaves from a path with a leaf blower. (Photo: Virginia State Parks/ CC BY 2.0)

“The less time you spend raking leaves, the more time you’ll have to enjoy the gorgeous fall weather and the wildlife that visits your garden.”

That’s the advice of National Wildlife Federation Naturalist David Mizejewski, who notes that raking, on top of being an annoying, inconvenient task that nobody really likes to do, also encourages people to put leaves into non-biodegradable plastic bags, after which they’ll get put into landfills, taking up a solid 13 percent of the country’s solid waste.

On the other hand, it’s not just about your garden. Leaves can also pose a danger to pedestrians. In 2014, I was walking around the neighborhood with my wife when I stepped on a pile of leaves, under which was a large divot in the sidewalk. I twisted my knee and was laid up for two days.

So, to rake or not to rake? Maybe just go with your gut on this one.

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook