After 130 Years, the Spoils of a Grave-Plundering Explorer Are Returning to Alaska

Righting at least one wrong from centuries of colonialism.

One day in 2015, John Johnson stood in a storage room in Berlin’s quiet Dahlem neighborhood, a long way from home, searching for the remains of his ancestors. He was accompanied by a group of European museum curators and two elders from his community in the Chugach region of Alaska, southeast of Anchorage. To underscore the reason for their visit, Johnson read aloud from a 19th-century travelogue by Norwegian explorer Johan Adrian Jacobsen.

In the 1880s, the Royal Ethnological Museum in Berlin sent Jacobsen on a mission through the Pacific Northwest and Alaska to collect Native American artifacts. Jacobsen returned with more than 7,000 items. He had traded for garments, carvings, and other objects from the indigenous people he encountered—but he also dug up burials, without consent.

Jacobsen’s travelogue is littered with rather clinical accounts of cemetery-robbing and mummy-stealing in the name of science. Johnson read from one particular passage that stuck with him. In it, Jacobsen describes finding the grave of a mother and child. The bodies were disintegrating in his hands so he just took the mother’s skull and dumped out the contents the cradle.

“We knew the travelogue, but it was a different kind of atmosphere when [Johnson] read it to us and asked us, ‘What happened to our ancestors?’” says Ilja Labischinski, a curatorial assistant who was there that day in the storage room in 2015. “It was tense. You feel a responsibility for what the people who worked at the museum did at that time.”

The human remains that Jacobsen brought to Germany have yet to be found. But this week, Johnson returned to Berlin to formally accept the repatriation of nine objects—including the cradle—that were taken from graves in the Chugach region. It is the first time the Ethnological Museum is returning part of its extensive collection to an indigenous community.

Johnson is vice president of cultural resources for the Chugach Alaska Corporation, created under the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971. He has become something of an explorer in his own right, and has traveled far in search of artifacts that were taken from his homeland—from wooden burial masks in the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C., to human remains at the National Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen.

The Chugach Alaska Corporation covers the coastal lands around Prince William Sound, where native tribes have lived for centuries. During the colonial era, the area was visited—and claimed—by several waves of Europeans. In 1778, Captain James Cook’s crew landed on the Kenai Peninsula and buried a bottle full of English coins to assert ownership of the land, in front of dozens of Dena’ina people. The Russians buried a bronze plate with an insignia. The Spanish buried a cross.

“I always get a kick out of it,” Johnson says. “I always say, we have the earliest and most valid claim because our ancestors have been buried in the hills for last 1,000 years. It’s not a bottle, it’s not a plate.”

In the 19th century, explorers such as Jacobsen took part in a scientific land grab for “exotic” and “authentic” artifacts from the remote parts of south-central Alaska (as well as countless other places). This was, ostensibly, for the benefit of those indigenous cultures. Editor Adrian Woldt captured the spirit of the era in his 1884 forward to Jacobsen’s travelogue: “European culture is engulfing and destroying the native peoples left in the world. Their customs and habits, legends and memories, weapons and artifacts are disappearing.… Mankind must therefore make every effort to collect, as the most valuable knowledge of the ancient past, all the objects pertaining to the development of culture.”

In their quest to “rescue” cultural objects from encroaching European culture, those Westerners didn’t seem to recognize the damage—or irony—of their actions.

Jacobsen was not shy about explaining his worldview. In his journal, he describes coming across a memorial to a person who had been killed by a bear: “Since this monument would be admired by many more people in the newly completed Royal Ethnological Museum in Berlin than here on the banks of the Yukon, and since it was made to be seen, I took it with me.”

Jacobsen was also aware that the indigenous people he met did not want him digging up graves, but this was little impediment to him. “He thought it was his duty to do it, in the name of science,” Labischinski says. In another episode, he describes taking three skulls from a burial ground near Vancouver Island, while pretending to be fishing and hunting. “In our haste I hurt my hand on the bone of a mummy and it bled profusely. We had scarcely stowed the skulls in the canoe when two Indians appeared who had followed us out of curiosity to see what we were doing,” he writes. “As soon as I saw them I shot at some sea gulls flying by, and this satisfied them. So we managed to get our booty on board unnoticed.”

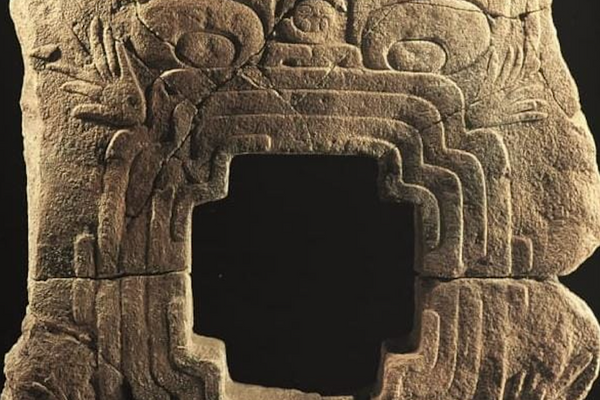

It was Jacobsen’s own detailed descriptions, in English translation, that led Johnson to believe that some Chugach grave goods might still be in Berlin. He wrote to the museum in 2015 and was invited to visit. After the delegation helped locate nine objects—several masks, an idol, and a baby carrier—that had been clearly taken from graves on Chugach lands, the long legal process to get the artifacts home began.

In May 2018, in the foyer of the now-closed Ethnological Museum, Johnson put on a pair of white gloves and posed for a photo with Hermann Parzinger, president of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation. They held between them one of the larger-than-life Chugach wooden masks. Johnson explained that the arrowhead-like shape of it symbolizes the belief that an individual’s head would turn into a point during the passage to the spirit world.

The Ethnological Museum is closed because next year its collection will move to the Humboldt Forum museum complex, a controversial €600-million project that has been criticized for its “colonial amnesia.” Art historian Bénédicte Savoy, who stepped down from the advisory board of the Humboldt Forum last year and has been a vocal critic, told Süddeutsche Zeitung that no ethnological museum should open today without properly investigating the origins of the objects it’s putting on display. “I want to know how much blood is dripping from each artwork,” Savoy said.

Though Germany has procedures for dealing with Nazi-looted art, cultural officials have been slow to investigate the provenance of objects collected during the colonial era. The country’s culture minister has just issued new guidelines on the restitution of objects from “colonial contexts.” But critics of the Humboldt Forum were disappointed that the guidelines imply that restitution will only take place if there is a legal basis for it, that is, only if legal and ethical standards were violated at the time of the acquisition.

What were the standards Jacobsen was working under? Johnson tries to put himself in the explorer’s shoes. “I’m sure it wouldn’t have been ethical if someone came to his hometown and looked around for that stuff and brought it back to Alaska,” he says. “It’s a touchy thing. If they were your relatives how would you react? But at that time so many collectors were doing it.” In the passage where Jacobsen describes finding the cradle, in fact, he laments that a researcher from the Smithsonian got to the burial ground first.

Ideally, the repatriated masks and other grave goods would go back to the pillow-lava caves and rock shelters where they had been laid to rest alongside the dead, Johnson says. But such a move would be too risky today, so the objects will go to a community cultural center. “To me repatriation is not the end, it’s just the beginning,” he says. And Johnson hasn’t given up on the idea that the mummies and other human remains collected by Jacobsen might still be somewhere in a Berlin storage room, far from home.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook