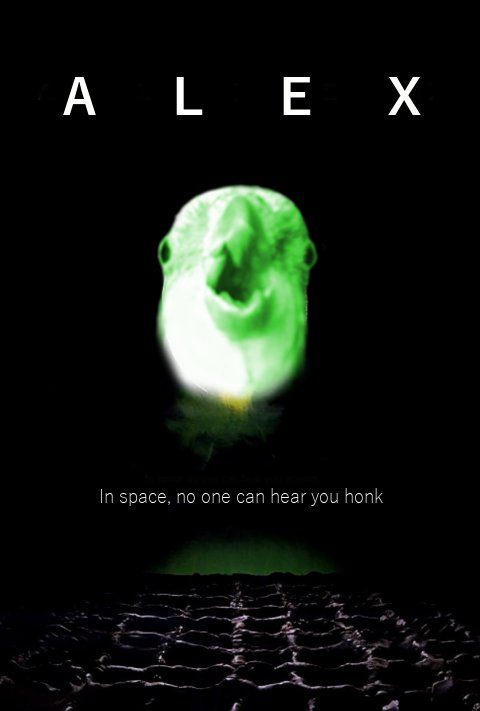

Alex the Honking Bird May Be the First Interspecies YouTube Celebrity

The distinctively voiced cockatiel has earned both human and avian fans.

Alex, a 20-year-old YouTube star from Brisbane, Australia, has the kind of weekday routine that makes your average working stiff jealous. Each morning, he greets the sun and hydrates. He eats a leisurely breakfast of greens, that his manager, Annika Howells, prepares and brings out for him. (He sleeps on the balcony.) The afternoon is dedicated to napping, chatting with neighbors, and grooming to keep up his good looks.

Evening is when the movie magic happens. As Alex goofs around with his son and housemate, Dominic—a YouTube up-and-comer himself—Howells keeps her phone nearby, in case they come up with something really good. A video from early February, in which Alex honks at various kitchen items, has pulled in about 130,000 views: not exactly Gangnam Style levels, but certainly not bad for a bird.

Alex—who goes by Alex the Honking Bird on his various social media platforms—is a rare thing: a YouTuber who has crossed the species line. In his burgeoning career as a celebrity cockatiel, Alex has earned human admirers, who enjoy watching him perform his trademark honking song. But he also has a growing legion of bird imitators, who flutter over when they hear his voice, and spend their spare time practicing their own honks. There’s that adage: On the internet, nobody knows you’re a dog. But what if everybody, including other birds, knows you’re a bird—and that’s why they like you?

Howells didn’t mean to teach Alex to honk. Young male cockatiels are very good at picking up sounds—as evidenced by a rash of birds that have learned to imitate microwaves, tooth-brushing, and that one burbly iPhone ringtone—and their human companions will often take advantage of this skill by teaching them particular whistles. This is both fun and practical: parrots tend to pair-bond with their owners, and as one bird lover explains, “Even if your bird can’t see you, they want to know you’re still around.” Establishing a particular “What’s up!” whistle, or contact call, keeps bird and human reassured, even when they’re in different rooms.

Howells can’t whistle, so when she got Alex nearly 20 years ago, she found a creative way to keep up her end of the bargain: Instead of encouraging Alex to imitate her, she imitated him. “When I got him, he would do this little squeak and bob his head,” she says. “So I would do the little squeak and bob my head back at him.” He would mimic her in turn, she says, and “it just got exaggerated over time,” until one day it had evolved into his full-on, foghorn honk.

Alex spent years happily honking and headbanging with the members of his household, from humans to his fellow birds to various home furnishings and appliances. Howells would occasionally film him doing something cute and upload it to YouTube, so she could share it with friends and family. Last summer, for whatever reason, other people started finding an older video, “Cockatiel reacts to plush toy version of himself,” in which Alex makes friends with an enormous stuffed bird.

“I don’t know if an algorithm got tweaked or something,” Howells says, “but all of a sudden it was getting all these views.” She licensed it to a viral video company, and it spread far and wide. When people started asking for more Alex, “I just kept running with it,” Howells says. She made him a Twitter account and a Facebook page and started posting videos more regularly, and Alex now has tens of thousands of followers on each platform.

As a human myself, I feel confident diagnosing why Alex’s videos are so popular with our species. Honking is funny, and the way Alex goes about it is particularly charming. As he loudly pistons around making his ceaseless racket, his big red cheeks make him look almost bashful: He can’t help it, he’s just gotta honk.

When putting together Alex’s social media presence, Howells leans into this. On Facebook, she has listed his profession as “Motivational Speaker.” “He’s like a little Labrador in a bird body,” she says. “Because he’s so happy and positive, I try to make all of his tweets and stuff the sort of thing I imagine Alex would say.”

Such things—“Just one honk at a time,” for example, or “Anything is possible when you carry a honk in your heart”—slotted easily into Bird Twitter and other online bird communities, which tend to be wholesome places: a mix of affirmations, funny videos, and pop-culture references tweaked for maximum bird inclusion. “Wii Honk Channel,” a video in which Alex’s honks are remixed and pitch-adjusted so that he “sings” the Nintendo Wii theme song, has racked up millions of views across various platforms. (“As a musician, what I can appreciate about Alex’s honks is that they have a consistent sound profile,” says the video’s creator, Anthony Armetta, who goes by Flaminglog. “That [and] he’s just so darned cute.”)

But if humans love his online persona, remix potential, and ebullient spirit, his avian fans, it seems, are mostly in it for the honks. Cockatiels and other parrots like hearing other birds, even onscreen ones, explains Rachel Binx, who has a cockatiel named Björd, and whose observations inspired this story. Owners will sometimes put on special mixes of cockatiel sounds, to keep their birds company while they’re away. But the existence of online bird communities has added a meta-level to this socialization strategy. “There are all these people who love birds, who are watching a bunch of bird videos,” she says. “And then their birds are interested in the videos too—they hear other birds and get really into it.”

Cats sometimes meow at cat videos, and dogs may bark at onscreen canine cameos. But some of Alex’s bird viewers take it one step further: they start honking, when they had never thought to honk before. Binx points out one cockatiel named Bob, whose owner regularly posts videos on the subreddit r/PartyParrot. When Bob hears Alex, his face lights up, and he now adds honk interludes to his singing. (When another user complimented the honks, his owner replied “Bob learned from the master.”) In the most recent upload, Bob looks right into the camera, imitates a small chirpy song that Alex sometimes sings at the start of videos, and starts honking like a clown nose. (Bob did not respond to a request for comment.)

He’s not the only one. A ringnecked parakeet named Baby started honking after her owner, Bryanna Harper, played Alex videos in her vicinity. “She picks up on a lot of things that I watch, but Alex is probably the fastest one she’s ever picked up on and clearly imitated,” says Harper.

My bird Lucky honks, or maybe he squeaks. He always does this when I play one of your videos! pic.twitter.com/hEuHWduxEV

— Chey 🎹🎼 (@kalend_cheyenne) March 1, 2018

Another Bob, this one a ringneck from from Gotland, Sweden, likes to watch Alex videos with his owner, who goes by Lovis. In a video Lovis sent me, Bob stands near a window and releases a cascade of honks, like an aspiring opera singer practicing his scales. He, too, often sprinkles honks into other vocalizations, Lovis says: “It’s like his own personal spin on it.”

Not everyone can honk, or wants to. Some birds instead will imitate Alex’s squeaky kissing noises, or his distinctive head bobs. Others are afraid, or just indifferent. (After all, YouTube trends aren’t for everyone.) Some humans actively protect their birds from Alex’s influence. Binx, for instance, says she is careful about Björd’s media diet: “I see him listening to [Alex],” she says. “But I have to keep in mind that any noise that I teach him or that he picks up, I will have to listen to for the next 20 years.”

What is it like to live with a bird memelord? “It’s very surreal seeing other birds making those noises,” says Howells. “I feel like I need to occasionally put out an apology to all of the humans—‘I’m sorry you all have weird-sounding birds now.’” Someone once told her they were going to play Alex’s videos out the window to see if a nearby flock of wild cockatiels would pick it up, but she never heard back about that experiment.

They try not to let fame interrupt the home dynamics. Dominic—Alex’s son with his late mate, Tina—makes regular cameos in Alex’s videos, but he generally prefers to indulge in lengthy bouts of scream-singing. “He did honk once, on Christmas morning,” says Howells, almost as if to prove that he could if he wanted to. “We called it the Honkmas Miracle. [But] he prefers to do his own thing.”

As for Alex, he’s remains much more of a tastemaker than a crowd-follower. Howells has tried to get him to imitate some of her favorite videos, like the one where a cockatiel sings the Totoro theme song, but he has proven tone-deaf. When she shows him his own videos, he doesn’t do much, either. His own first viewing of Wii Honk Channel elicited a kind of rapt befuddlement. “The first time in his life he had nothing to say,” says Howells.

“He can only really do one thing,” Howells continues. “But he does that one thing well.” On the Internet, that’s all it takes.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook