When Cow Tongue Was an Essential Thanksgiving Ingredient

It made American pies rich and indulgent.

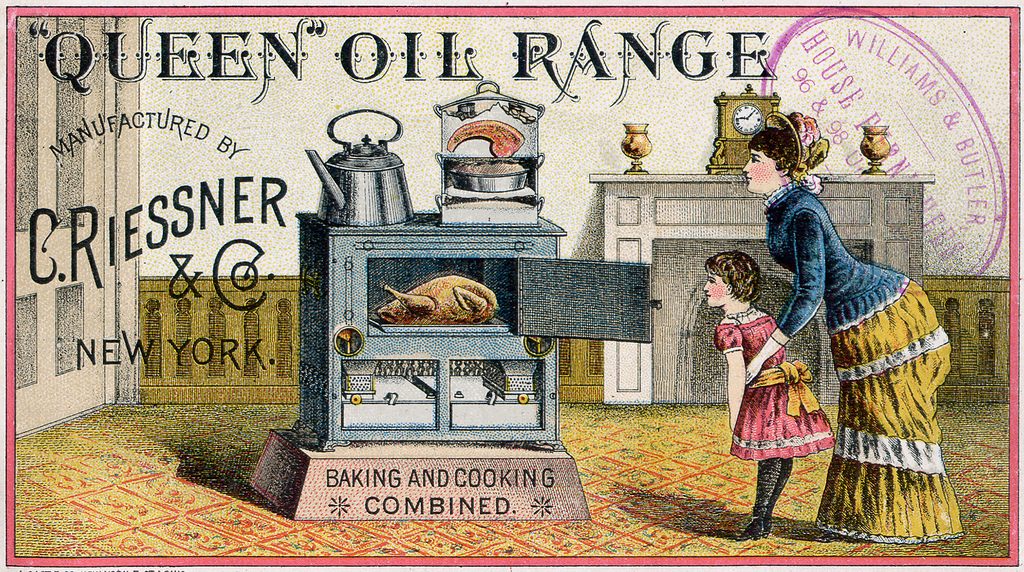

While families today might argue about whether to top their sweet potatoes with marshmallows or serve green beans with a mushroom-soup membrane, colonial cooks had different expectations for their Thanksgiving recipes. For one, pies were not just dessert. Meaty-yet-sweet mince pies, which descended from medieval European pies, held a special place at the Thanksgiving table. And one key ingredient of these indulgent pastries is long-forgotten: cow tongue.

Not until the 18th century did references to early Thanksgiving dishes make their way into the historical record, but most mention mince pie as a standard part of the feast. Pie, as a classic British food, made its way to colonial tables via the settlers. In Europe, the dish had long been a source of both sustenance and entertainment: Pie crusts, which were once called coffyns, were sturdy enough to double as containers and could hold fillings both cooked and living (such as the ever popular “four and twenty blackbirds” pie).

One of the most popular pastry coffyn fillings, however, was, mincemeat: a combination of finely chopped and cooked meat, sweeter ingredients such as apples, currants, and raisins, alcohol such as brandy, and beef fat (suet). Part of mincemeat’s popularity came from its function as a useful way to repurpose leftover or unused ingredients, from vegetables to meat scraps, such as offal or organ meats. Cooks could prepare the pies in advance, and after a hearty mincemeat dinner or breakfast (mince meat could be eaten any time of day), farmers could carry their leftovers into the field.

But on Thanksgiving, mincemeat tongue pie was far from a frugal affair, and represented a particularly indulgent treat. The first American cookbook, American Cookery, published in 1796, includes three mince pie recipes. One recipe hints that cow feet and tongue (referred to as “neet”) were among the most prized ingredients for holiday feasting. The recipe also called for a third pound of sugar, a quarter pound of butter, a pint of wine, and a pound of raisins, and later recipes included apples, brandy, lemon, and “corn meat.” These pies were so decadent that the Mother of Thanksgiving herself, Josefa Hale, wrote, “They are considered indispensable; but I may be allowed to hope that during the remainder of the year, this rich, expensive, and exceedingly unhealthy diet will be used very sparingly by all who wish to enjoy sound sleep or pleasant dreams.” She goes on to decree that they should never be served to children.

How could an organ meat be considered integral to a festive Thanksgiving pie, and so rich and tasty that it tested Puritan sensibilities? According to food scholar Bruce Kraig, author of A Rich and Fertile Land: A History of Food in America, fresh tongue (as opposed to pickled tongue, as it was often eaten) offered a rich fattiness to mince pies. Similar to cow feet, tongue is rich in collagen and, when cooked for a long time, creates a tender and gelatinous structure and an unctuous, mouth-coating texture. Combined with sugar, alcohol, and dried fruits, the hefty pie was a true bounty.

But with all that flavor, “neet’s tongue” and “neet’s feet” eventually disappeared from the Thanksgiving table. According to Kraig, it’s possible that children started distancing themselves from old tastes and traditions. As wealth increased, “muscle meats” also became more popular, until the “meat” in mince meat was merely a vestige.

Sweet mince pies hung around for a few more decades: A 1903 Heinz advertisement reads “Mince Pies for Thanksgiving Time” and boasts that “a single trial will convince you of its superiority.” But by the 1950s, Americans prepared more JELL-O salad than jellied meat for Thanksgiving. Today, both dishes seem quaint, and have been banished from many turkey-topped tables. But as with most trends, perhaps by next Thanksgiving, a morsel of minced tongue will make its comeback to the holiday menu.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook