Turning Anatomical Drawings Into Mosaics, Stone by Stone

An artist is making massive monuments to medical illustration.

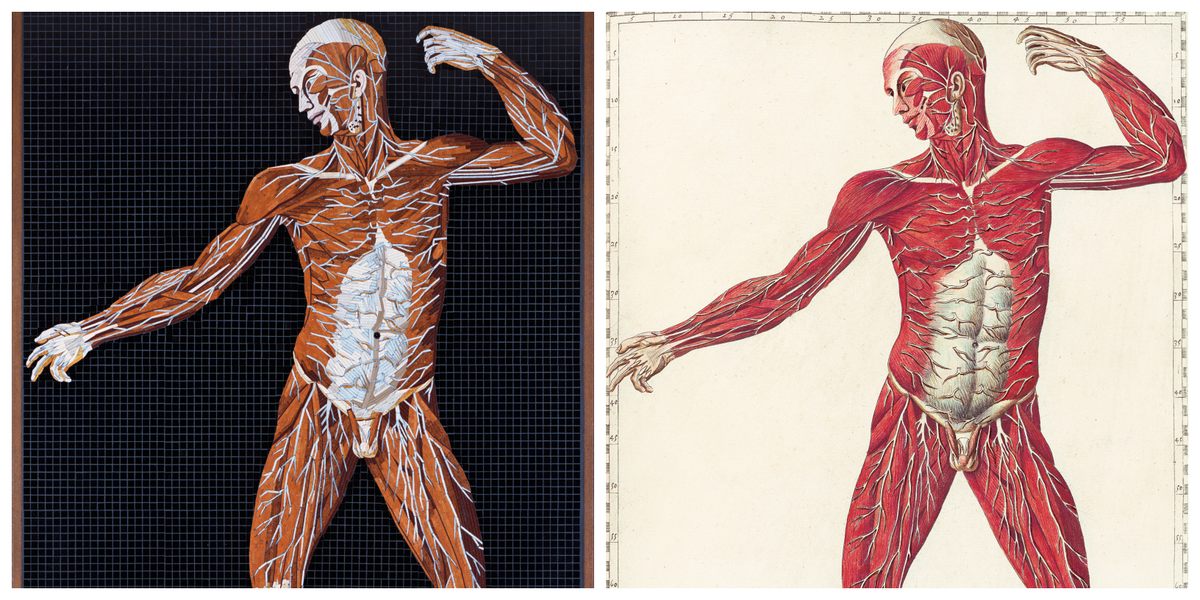

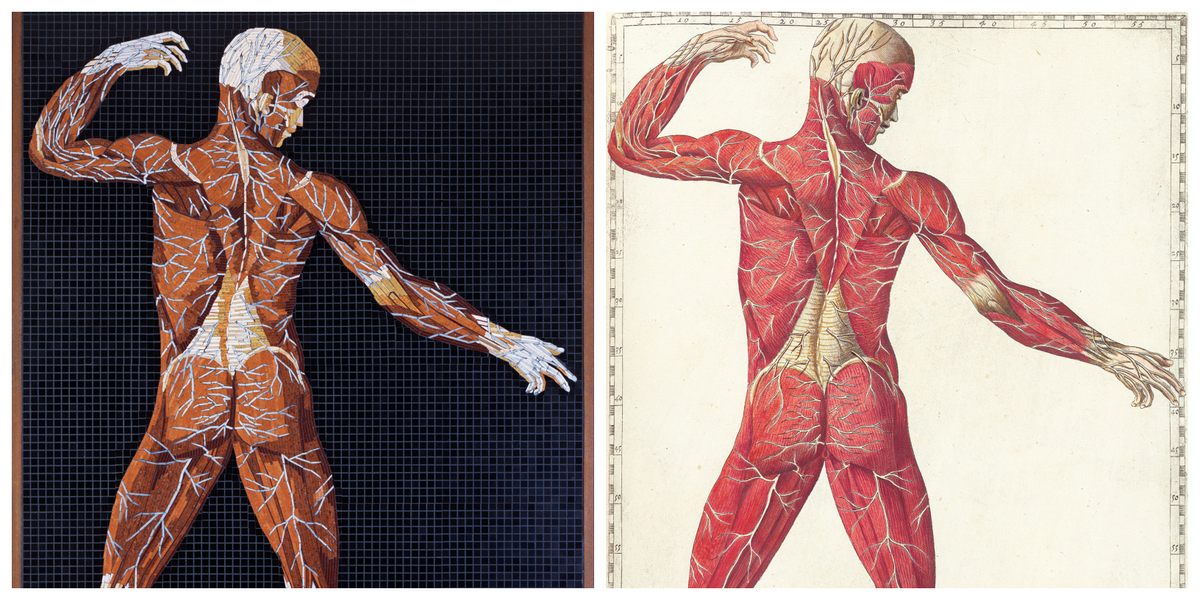

The trapezius, the latissimus dorsi, the hamstrings—those were easy. Long swaths of sinew lend themselves to big strips of stone. The short muscles around the ribcage, though—those are hard. The nervous system, branching like lacy coral, is harder still. Even so, John T. Unger, an artist based in Hudson, New York, is working his way through the body—from head to toe and down into the muscles, bones, eyeballs, and belly button—by making massive mosaics based on the work of the 16th-century anatomist Bartholomeo Eustachi.

Eustachi died in 1574, but the first edition of Tabulae anatomicae, a volume dedicated to his findings, wasn’t published until 140 years later. In the accompanying copperplate engravings, made by Giulio de Musi, figures contort in effortlessly elegant poses—they’re as lithe and nimble as dancers, but nude and stripped of skin. These images remain more obscure than those of fellow 16th-century anatomist Andreas Vesalius, whose De humani corporis fabrica corrected a lot of assumptions that originated when anatomists turned to animal corpses in eras when the church frowned on dissecting human bodies. Unger consulted a 1783 edition of Eustachi’s work, digitized by the U.S. National Library of Medicine, which featured hand-colored plates that showcase muscles, bones, and tendons in various ruddy shades. For a mosaicist, Eustachi’s images have an advantage over Vesalius’s renowned black-and-white ones: Since the tissue is already colored in the source material, it’s easier to match stones to the hues.

That’s something Unger has worked hard to get right. “Marble comes in just the right colors to do an anatomical drawing,” he says. Unger is making 14 mosaics in all, each weighing between 300 and 350 pounds, depending on the backing and mortar, and spanning roughly four feet by seven feet. Because he wanted the colors to feel cohesive across them, Unger bought as much stone as he could upfront. (Since marble is so heavy, several tons of it “really fits in a corner of a small garage,” he says.)

In addition to the images from the National Library of Medicine, Unger also paged through a stack of anatomy books including hand-me-down volumes from his wife, who works as a nurse. To bring the muscles to life, he figured he needed three colors of brownish, reddish stone—that would be enough to create convincing shading. Buying in bulk matters because variation is natural, Unger adds: “If you go to a quarry and buy the same stone by name a week later, the color may change.”

In the illustrations, some of the figures’ skin has a pale blue cast. To emulate it, Unger tracked down stone from a specific quarry in South America. He also spent months puzzling out how to convey the crosshatching the engraver had used on the figures’ hands and feet. Eventually, he cracked it, settling on slicing striated limestone lengthwise, diagonally, and into chevron patterns. He stocked up on onyx from Arizona, black marble for belly buttons, and rubies for the figures’ glassy eyes. “By the time I’m done,” he says, “I will have cut two or three linear miles of stone.”

Unger began the project in earnest in 2015, though he started noodling over it nearly a decade earlier. “I was in over my head from the get-go,” he says, but he’s refined the work over time, graduating from pre-cut squares to the equipment he needs to cut stubborn materials down into fine, tiny pieces just a few millimeters thick. “The deeper I go down this rabbit hole, the better I get at it,” he says.

The mosaics are still Unger’s passion project, in every sense. By day, he fashions luxurious-looking fireplaces made from old industrial tanks. These are the bread and butter of his artistic work—the little domes flanked by carved flames or shooting comets are how he affords to buy supplies for the mosaics, and justifies working on them late into the night. He’ll display what he’s finished so far at an exhibition at the Carrie Haddad Gallery in Hudson in June and July 2019. Eventually, he hopes to send the finished product on the road as a touring show, and the secure the mosaics a permanent place in a museum collection.

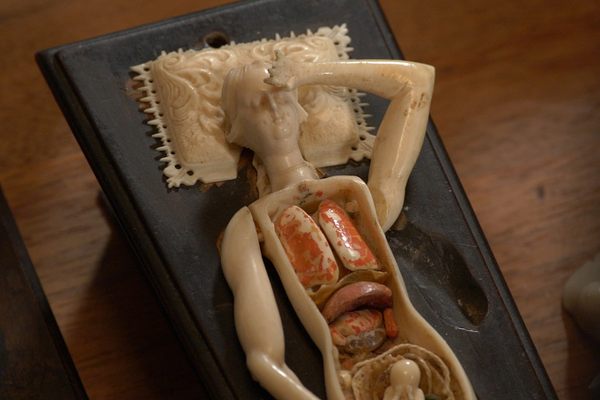

He’s optimistic about his prospects, because mosaics have staying power—literally and metaphorically. Ancient examples testify to the medium’s enduring appeal and hardiness, and while medical practices and protocol have changed since Eustachi’s day (the title page of his volume shows people poking and prodding at a flayed-open body cavity with their bare hands, while dogs rip into the entrails on the floor), humans are still far from solving all of the body’s mysteries. If Unger can’t find a home for his work, he’ll turn his monumental project into a monument of a different kind. “I may build a vault on the little mountain where I live,” he says, “and have them buried around me.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook