Reintroducing the Big-Game Huntresses of the Ancient World

Men hunted, women gathered, right? It’s a lot more complicated.

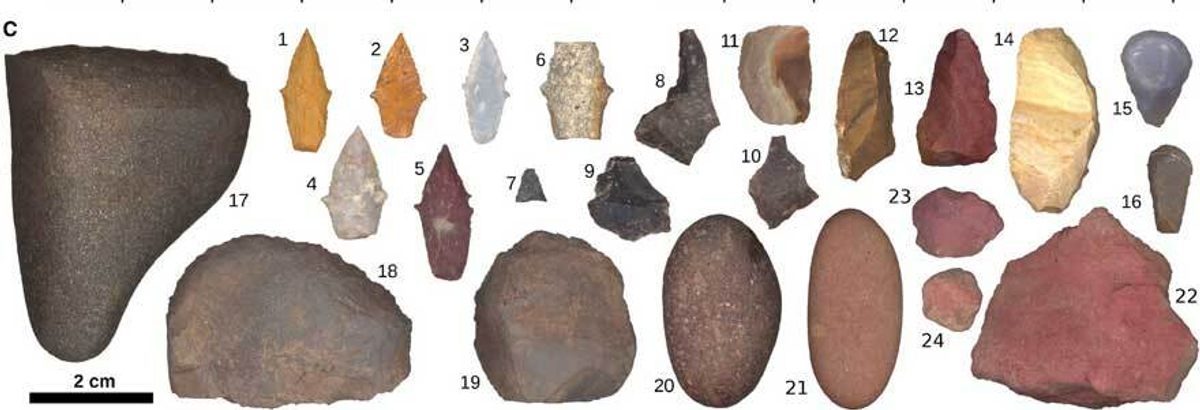

In 2018, when an international team of anthropologists unearthed 9,000-year-old human remains in the Peruvian altiplano, on the western shore of Lake Titicaca, they assumed two things. Because the person was buried with a trove of hunting tools, the researchers figured the individual, dubbed WMP6, had been a powerful, male hunter, able to take down big game like deer and vicuña, a relative of the llama.

Weeks later, however, the team walked back some of those assumptions. Based on “the gracility of the individual, the lack of musculature, and slight nature” of the leg bones and a degraded cranium, Jim Watson, an anthropologist and osteologist at the University of Arizona, surmised that the person might have been female. Drawing on analysis of a sex-linked protein from WMP6’s dental enamel, the team confirmed that WMP6 was a huntress in her late teens.

A closer look at remains from hundreds of burial sites throughout the region painted a similar picture: Combing through public records of 429 Central and South American burials from the late Pleistocene and early Holocene period, the team found 27 instances of people buried with hunting artifacts—and 11 were female. The findings, published earlier this month in Science Advances, flew in the face of the notion that within hunter-gatherer societies, men hunted and women gathered.

In the past, “archaeologists usually dismissed associations of women with hunting artifacts as misconstrued or [thought] maybe the sex estimation was wrong,” says Watson, a co-author of the paper. Individually, these huntresses were seen as exceptions to the rule; upon closer analysis, however, the team declared that big-game hunting was likely gender neutral in the ancient Latin American world.

The conclusion was met with varied reactions. Some of the field’s “old guard” derided the findings as an overreach, Watson says; burial goods are too inconclusive to ever support such a hefty thesis, they held. (“The interpretation of grave goods as a cultural, symbolic act, is not simple or straightforward,” Robert L. Kelly, an anthropologist at the University of Wyoming, told The New York Times.) Some progressive experts besmirched the paper as unnewsworthy: “They thought we were sensationalizing the idea of the female hunter—that of course we know there were female hunters…and that we were just pandering to the press,” Watson adds.

For many archaeologists and anthropologists, ancient big-game huntresses need no introduction—their existence has been known among professionals for decades. For the rest of us, these findings contradict a half-century of assumptions, mostly stemming from a 1966 symposium at the University of Chicago and subsequent book titled simply Man the Hunter. The symposium focused on hunting as integral to human evolution and, based on knowledge of contemporary hunter-gatherer societies, put forth the idea that (with few exceptions) it was a male act. Beyond those few scenarios, women were primarily mentioned in the symposium and book for their reproductive capacities. These claims set the tone in the field for decades.

“I know in my own research it’s been hard to challenge that paradigm,” says Marin Pilloud, an anthropologist from the University of Nevada, Reno. She studies similarities in blunt-force trauma and patterns of violence between prehistoric Californian male and female skeletons to decipher the role of gender in ancient warfare, and believes the lens of modernity can obscure or manipulate our understanding of the past. “The past can serve to legitimize the present,” she says, including gender norms that hang on today. Pilloud applauded and defended the paper as making room for a more nuanced understanding of gender, and noted that if WMP6 had been male, no one would question his role as a big-game hunter.

Christine Lee, an archaeologist with Cal State, Los Angeles, agrees. “I liked the open attitude of ‘Why wouldn’t she be [a hunter]?’” says Lee, who studies the remains of Mongolian warrior women from the tumultuous Xianbei period whose skeletal patterns indicate regular horseback riding, bow-drawing, and war wounds. She appreciated the paper’s rebuke of past archaeologists who “clung to this very 20th century view…that if a woman was pregnant she couldn’t hurl an atlatl (a spear-throwing lever) or that if she was carrying children she couldn’t use a bow-and-arrow.” While Lee is pleased with the paper, she can’t help but feel gender, ironically, played a role in its success. The lead co-authors’ reputations as intrepid, hardy types precedes them: “They’re very well-known, rugged, archaeology men, out there in the middle of nowhere, no electricity, no toilet…and I think it takes that type of man saying this to make other, older men within the establishment listen.”

The artist’s reconstruction of an ancient big-game huntress in action also sparked particular controversy on Twitter. The illustration depicts a woman donning a reddish tunic (and a sort of Pleistocene-chic up-do), rearing back an atlatl to take down a frightened vicuña in a prehistoric altiplano setting. “Gender roles were fluid in the past!” read one tweet, “but also let’s dress her in pink so it’s really clear she’s a woman.” The gripes were undue, Watson explains: The clothing and hairstyling drew from rock-art imagery, and the tunic color was based on red ochre—an iron-ore mineral commonly used to process hides—found aside WMP6’s remains.

For all the fuss and in-squabbling over the details of the paper, anthropologist Carolyn Hodges-Simeon of Boston University has a more macro perspective on its release. Well-intentioned as it may be, she sees the woman-as-hunter narrative undervaluing the work of gathering. “There’s this idea that hunting is the important thing and gathering is just flitting through the forest picking fruit off of trees, and that’s not at all the case,” she says. Gathering, she adds, is just as physically demanding, requires generations of built-up knowledge, and can—as with the !Kung tribes of the Kalahari Desert—provide the majority of a foraging community’s caloric intake.

For Hodges-Simeon, present-day dynamics don’t call for archaeological backing. “We don’t need men and women to have done the same kind of work throughout evolutionary history to have the belief that men and women should be paid for equal work.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook