Romans Once Filled the Colosseum with Water and Staged an Epic Mock Sea Battle

An artist’s rendering of an ancient Roman naumachia. The emperor’s got some serious front row seats. (Image: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Being appointed party planner in ancient Rome for a simulated naval battle, or naumachia, would be a nightmare. Consider the logistics behind staging one of these manic events in a lake, arena, or artificially constructed basin: flooding and then draining the water, organizing all the condemned criminals and prisoners of war, procuring the right weapons, managing the spectators, arranging the boats (biremes, triremes, and even quinqueremes), orchestrating the fighting, overseeing security, importing sea creatures, keeping tabs on brothels, and of course, pleasing the emperor.

If you messed up the head honcho’s celebration, he might just throw you into the cess pool and cheer you on as you fend for your life.

A fleet of boats, thousands of oarsmen, utter chaos. (Image: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Naumachiae are thought to date back to the third century BC, and appear to have taken place only four or five times in history. The term itself, which translates to “naval combat,” can signify both the event itself and the place where it took place. As massive ordeals requiring far more resources than your average Roman spectacle, naumachiae were only orchestrated for exceptionally celebratory occasions. You can think of a naumachia kind of as gladiator battle scaled up and tossed into an enormous pool, with competing fleets of oarsmen and fighters loosely reenacting a historical battle, or simply improvising their brutality. (Men already awaiting execution sometimes needed to be goaded into killing each other for the sake of mass entertainment. Oh, ancient Rome.)

A true extravaganza. (Image: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

The first naumachia on record, in 46 BC, was in honor Julius Caesar’s quadruple triumph, which ended wars in Gaul, Egypt, against Pharnaces of Pontus, and against King Juba of Numidia. The naumachia was a centerpiece in an extravaganza also involving music, horse-racing, infantry and cavalry combat, and a few low-key elephant battles. Aquatic displays and general over-the-top antics were popular at the time, though not much is known about them in detail.

Another sort of nautical spectacle, this one apparently involving sea monsters. (Image: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

For Caesar’s naumachia, ships representing the Tyrian and Egyptian fleets were set afloat in a basin constructed near the river Tiber. The boats were staffed with 4,000 oarsmen and 2,000 fighting men. It’s unclear how much of the ensuing face off was pre-orchestrated, how much was theatrical, and how much was simply bloody mayhem, but whatever the case, the scale and novelty of the spectacle drew thousands of spectators who crowded and even camped along the streets to catch a glimpse. In the chaotic frenzy, spectators even ended up trampled to death in their eagerness to see boats clash and blood spilled.

Another aspect of the mass spectacle was a sexual one. The poet Ovid wrote of a later naumachia, “With such a throng, who could not fail to find what caught his fancy?” A naumachia, with its crowds and chaos, was rife with drunkenness and debauchery and abundant opportunities for anonymous trysts and dalliances between men or women. Prostitutes and brothels were also a part of many festivities.

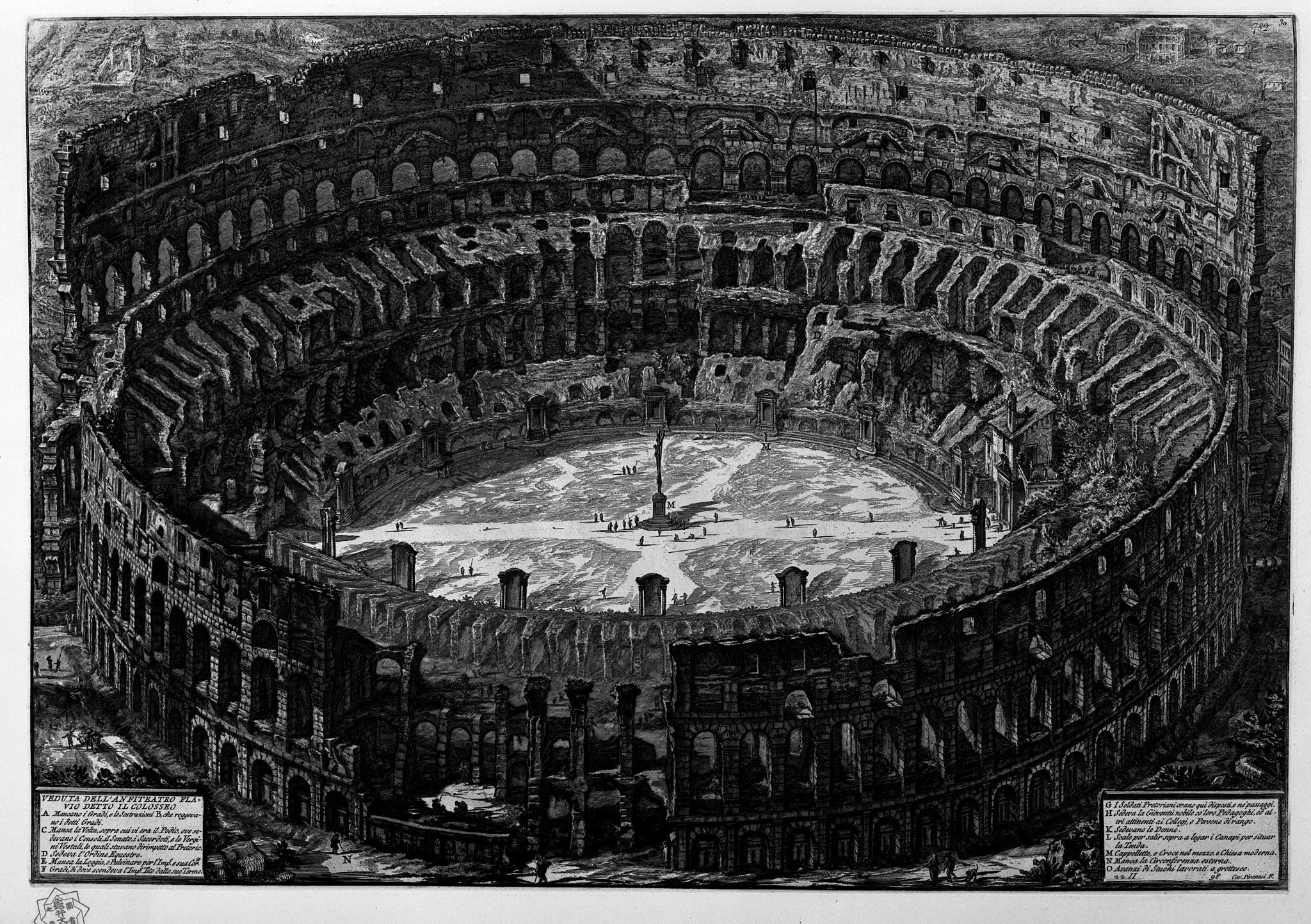

Imagine trying to fill this thing up with water. (Image: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Augustus threw a naumachia in 2 BC involving a basin broad enough to hold 30 ships representing Persian and Athenian fleets. A bit later, in 52 AD, Claudius demanded his own naumachia, this one on a lake and involving 19,000 soldiers and 100 ships meant to represent rivals Rhodes and Cecily. According to Tacitus, the prisoners at this showcase refused to fight, forcing Claudius to send down his imperial guard to instigate some blood shedding.

In 57 AD, Nero held a naumachia in a wooden amphitheater filled not only with water, but also with water creatures such as seals and hippos (though it’s unclear what happened to the imported marine life when the water was immediately after drained from the amphitheater to make room for a land contest). A few decades later, in AD 80, the third day of a multi-day, multi-activity extravaganza dedicated to Titus featured a naval standoff of 3,000 men.

The natural venue for an event of this scale would, of course, be Colosseum itself. Details are a bit sketchy, but Romans did apparently try to turn the gladiatorial ring into waterworld at least once. According to Roman historian Cassius Dio (235 AD), a sea fight did take place in the famed amphitheater in 86 AD; it apparently involved a violent rainstorm that led to the deaths of all the combatants as well as many of the spectators. Underground chambers beneath the Colosseum support this possibility, though it’s a puzzle to imagine imperial event managers somehow pumping enough water to float a fleet of boats into the world’s largest amphitheater. Stranger things have happened, but not often.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook