Capturing Sri Lanka’s Ancient, Almost Lost Martial Art

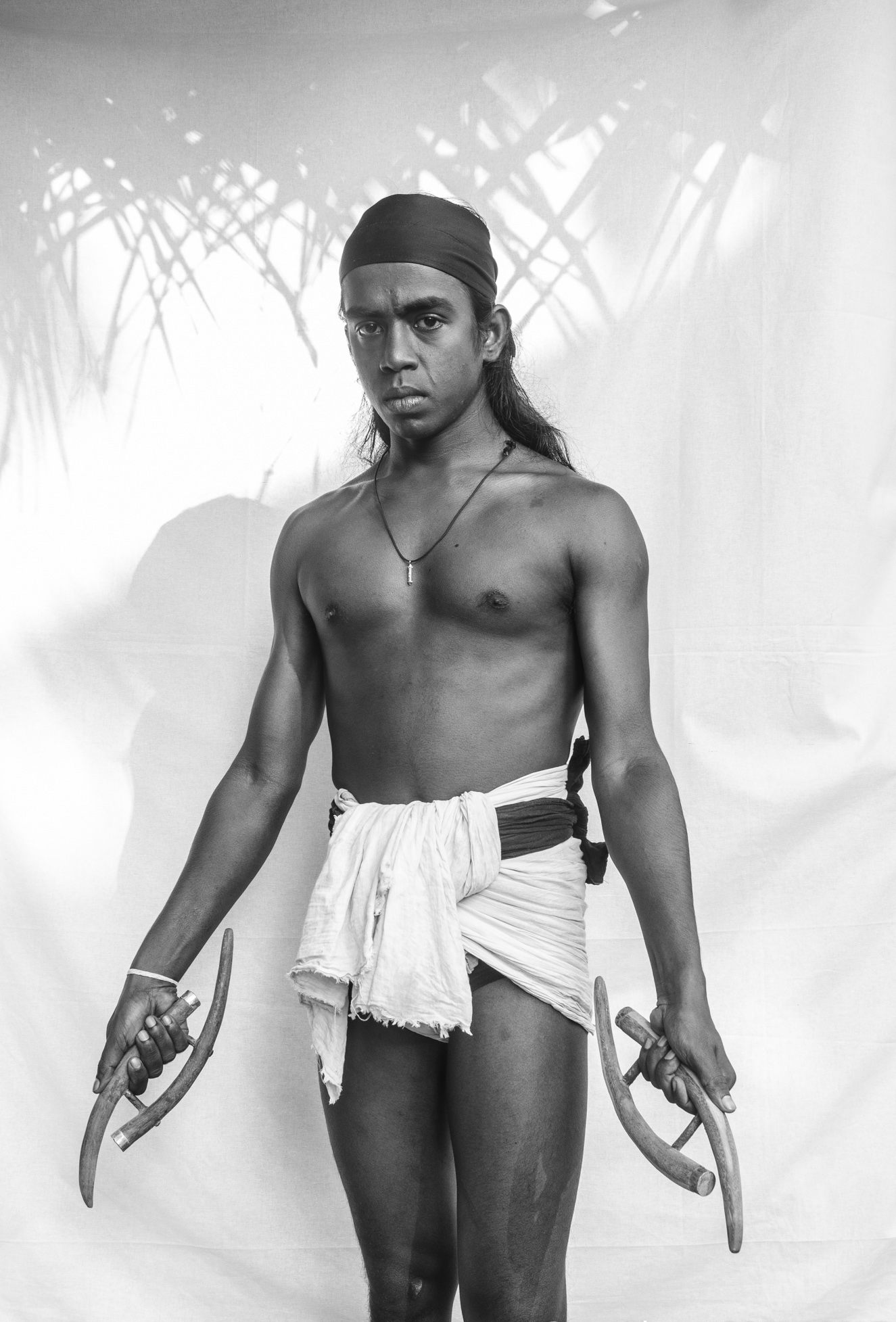

Photographer Reza Akram spent seven years documenting angampora, an indigenous fighting style banned by British colonizers.

When Portuguese colonizers came to Sri Lanka in the early 16th century, it set off decades of warfare. Prominent in these battles were local warriors who practiced angampora, a traditional martial art that had been used to protect the island for millennia, involving unarmed combat, weaponry, and incantations. The Portuguese came to occupy part of the island and were followed by the Dutch and then the British, who finally conquered what was then known as Ceylon in 1815. Following the Uva-Wellassa uprising, also known as the Great Liberation War, in 1817 and 1818, Governor Robert Brownrigg banned angampora, figuring that a populace trained in hand-to-hand combat would be more difficult to control.

The British imprisoned angampora warriors, and it is said they took extreme measures—shooting practitioners of the fighting style in the knees. The martial art was almost lost, practiced only by a handful of aging masters who decamped to rural villages to continue their practice in secret.

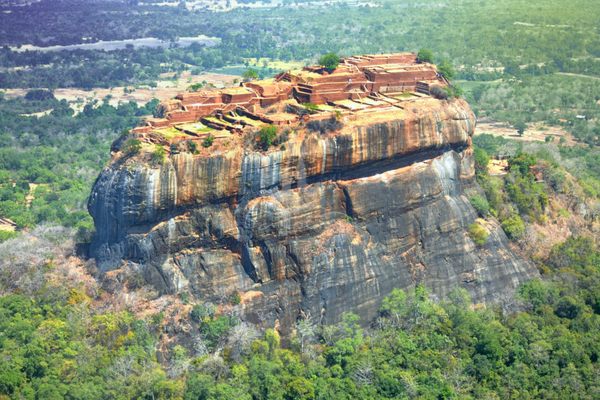

Two centuries later, Colombo-based photographer Reza Akram shows off a photo: three armed men sparring on a rocky outcrop overlooking marshes below. “They are actual angampora warriors,” he says. It’s just one of thousands of images that Akram captured over seven years, of the people who have kept this martial art alive. And his work has helped drive a modern surge in interest in angampora.

Angampora: A Nation’s Legacy in Pictures is a coffee-table book, authored by angampora master Ajantha Mahantharachchi and featuring some 700 of Akram’s striking photos.

Atlas Obscura spoke with Akram about documenting a lost martial art, pressure points, and how hard it is to stop once you’ve gone down a rabbit hole.

What started your love of photography?

I think I was 12 when I first took my father’s old camera. You can tell that I stole it, because, you see, he didn’t give me his camera. My father was a chartered accountant. His other kids went on to do office jobs like him. I was the rebel child. I wanted to take photos of skies and trees and wildlife. I sometimes borrowed my friends’ cameras and practiced with senior photographers who became my mentors. For me, the camera was a brilliant passport to explore places. Thanks to the craft, I did things I’d never be able to do otherwise. As part of the book, I cataloged museum artifacts, walked into the inside of the Temple of the Sacred Tooth Relic, and worked with fierce angampora warrior families.

But when I first went to college to study photography, I did three jobs. After exactly three months, I didn’t have money to pay for college. When I asked them for a scholarship, they told me that you shouldn’t study if you don’t have money. So I left. I later got qualifications, but I mostly practiced the craft myself, and learned a lot from several mentors.

How did you first learn about angampora?

I became interested in action photography, and always wanted to do something unique. So I was always looking for new ideas, but they never popped up, until one day when I went to the home of a friend.

On this particular day, he had changed the screensaver on his computer. It was three men, battling. That was it. This picture fascinated me. I asked my friend what it was. “You don’t know?,” he looked at me like I never went to school. “It’s angampora.”

So, for two years, I took photos of angampora events, but nothing really worked. I was just shooting hundreds of photos without purpose. But the years of freelancing have taught me one thing: patience. Good things take time.

Then Dr. Mahantharachchi—I call him gurunnanse [master] was conducting an event in Ampara in eastern Sri Lanka. I asked him if I could shoot some pictures. He told me he’s planning to author a book and would like to have some pictures taken. That was wonderful—I never thought my photos could be in a book.

How did you proceed with the project?

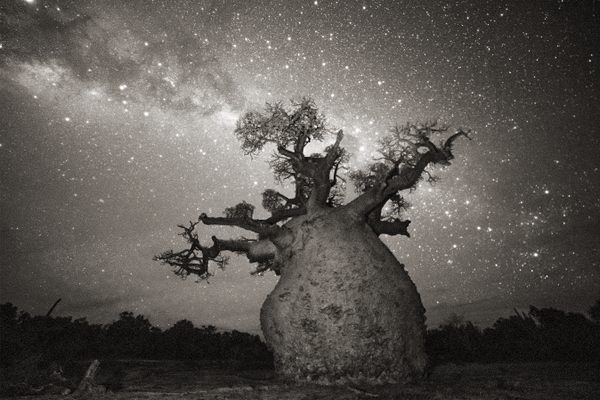

The day of the photoshoot in Ampara, it rained heavily. Once it slowed down, I took some monochrome pictures against the inky skies and put them on Behance. One day, I received an email from Huffington Post. We had a Skype interview. Several weeks went by, and I forgot about the interview, then a mentor rang me. She congratulated me, and I’m like, “What are you talking about?” “The fighters,” she laughed. This article became a hit and got translated into local languages.

This was when my friend Yasas Ratnayake and I realized that people wanted to see and know more about angampora. We planned our chapters, and Yasas and I documented our work on Instagram. In each chapter, I would decide how I could employ visual aspects to match the story. For example, there’s a chapter about incantations. I wanted to keep that chapter as dark as ever; it was full of shadows to extend the suspense of the viewer. Then we planned themes and locations for each chapter. We shot most photos in stunning landscapes across Sri Lanka. I saw every location before I took photos. Plan twice, shoot once, that was my go-to rule. For the whole book, I used three lenses and two flashes. From there, I developed the style of shooting with minimal equipment.

What was your research into angampora like?

It’s like diving deep into a rabbit hole. There’s so much about angampora, from the history to artifacts to dancing and indigenous healing. In the end, we had to stop learning more. We were shooting so much. The book was getting delayed because we were finding new things about the subject. But we needed to put the book together.

You took 28,000 images over seven years?

Crazy, I know. I was emotionally attached to all my pictures, but only 700 could make it to the book. Picking those 700 was the most difficult task. Have you ever heard a mum saying her kids are ugly? It’s like that. Your photos are your babies, so you can never abandon them.

On the other hand, seven years is a long time to grow as an artist, but I had to make sure my craft stayed the same. That was my focus. The visual language should stay constant throughout the project. It was a big learning curve for me.

Did people tell you what fascinated them the most about these photos?

Photos of women warriors always fascinated people. Before colonial times, women played a big role in angampora. They led armies and used weaponry. This is something we take for granted in today’s age—after the administration of British Victorian values in the 19th century, it became less and less common for women to take part in anything outside their homes. I wanted to give the same badass warrior look to them, while at certain points recreating the modest look. Everything is authentically correct in these photos, from dresses to weapons and warriors you see.

What moments stand out to you from the project?

Hundreds of them. I’ll tell you one thing. One day, Yasas came to the shooting location. Everything was new to him. One of the techniques in angampora is attacking pressure points in the body. I’ve seen enough people getting attacked this way, which looked awfully painful. Yasas thought it was nothing. He went to Dr. Mahantharachchi and said, “Gurunnanse, so these pressure points aren’t real. Are they?” Gurunnase replied, “Let me show you.” Yasas thought he was up for it. Gurunaase just held his hand and twisted it. Yasas just collapsed, screaming.

Another day, we visited one of the oldest angampora practitioners. This master was 104 years old. He had been bedridden for five months. But when we went to meet him, he overheard us talking to his granddaughter, and he got up from his bed, growled at his grandkids for not telling him, and then asked for his weapons and started showing his skills. What I saw there was a person’s love and passion for a craft that kept them going throughout their life. Two months later, he passed away. Things like that inspired me and motivated me to carry on despite the barriers, and there were many of them: lack of equipment, time, money, you name it.

What are you working on now?

I have a couple of ideas in the baby stage now. As soon as I finished angampora, I had to do another coffee table project called Shilla, about Sri Lanka’s minerals. I went from action-packed to non-moving. And they are all either massive mountain-like formations or, like, a grain of salt. I needed to make it interesting. That’s when my years of experience kicked in. It’s your perspective and the effort you put in.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook