Hunting for Famous Architects’ Forgotten Design-School Projects

These drawings and models show where hallmark styles were born.

Architecture students end their semesters sleep-deprived and often half-mad with caffeine, standing before juries of professors and peers. They try to sound coherent while explaining their final projects’ renderings and models and their visions of improving cityscapes. Once the course grades come in, the drawings and 3D constructions typically get stashed away in dorm rooms or university cupboards, never to be seen again, or perhaps to be pulled out occasionally with cringes or misty-eyed pangs by architects who changed their styles again and again during long careers.

At a few architectural institutions, however, there will be no forgetting of youthful submissions anymore. Librarians and archivists are creating searchable databases of classroom projects and competition entries produced in the last century. The digitized images reveal what students have imagined building without real-world limitations of budget or even rules of gravity—why not, before you actually have to earn a living, think about adding islands full of obelisks to the Manhattan shoreline or hanging urban observation pods from streetlights?

“It’s the impossible dreams” that turn up in the classwork records, explains Steven Hillyer, the director of the architecture school archive at the Cooper Union in Manhattan.

The Van Alen Institute in New York is posting over a century’s worth of student proposals, starting with rather elitist ideas for yacht harbors and riding schools. The Cooper Union has excavated classroom work dating back to curvaceous hot dog stand concepts suggested for the 1939 World’s Fair, and a comprehensive database of the material—even including transcripts of students’ presentations and teachers’ remarks—is scheduled to go live in the next year or so.

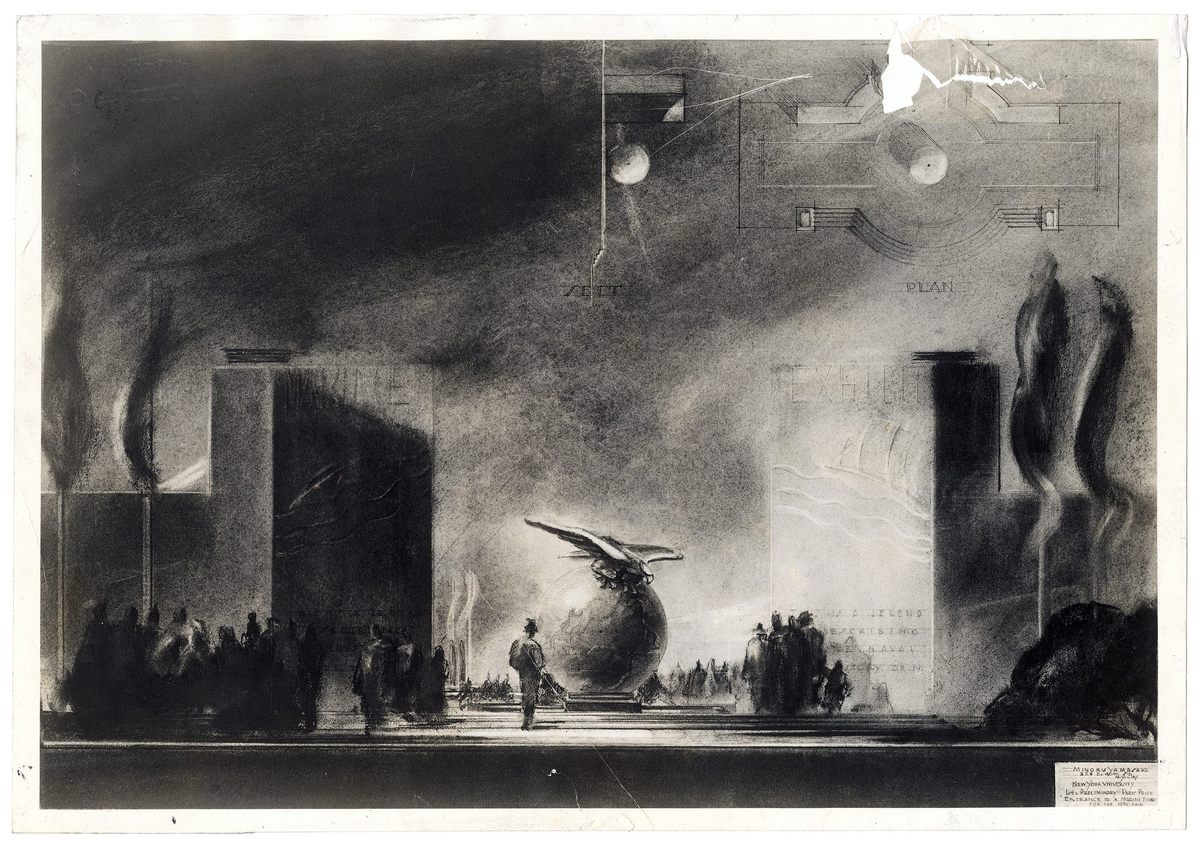

In the early 1900s, as the databases in progress show, ethnically diverse students from humble backgrounds made inroads in the WASP-dominated architecture profession and went on to fame. The Van Alen boxes contain ideas for neoclassical and Art Deco compounds from the 1920s and ‘30s by the future influential modernists Percival Goodman, Max Abramowitz and George Nelson. In the institute’s late 1930s entries, Minoru Yamasaki, the future designer of the World Trade Center, sketched prophetic pairs of blocky towers.

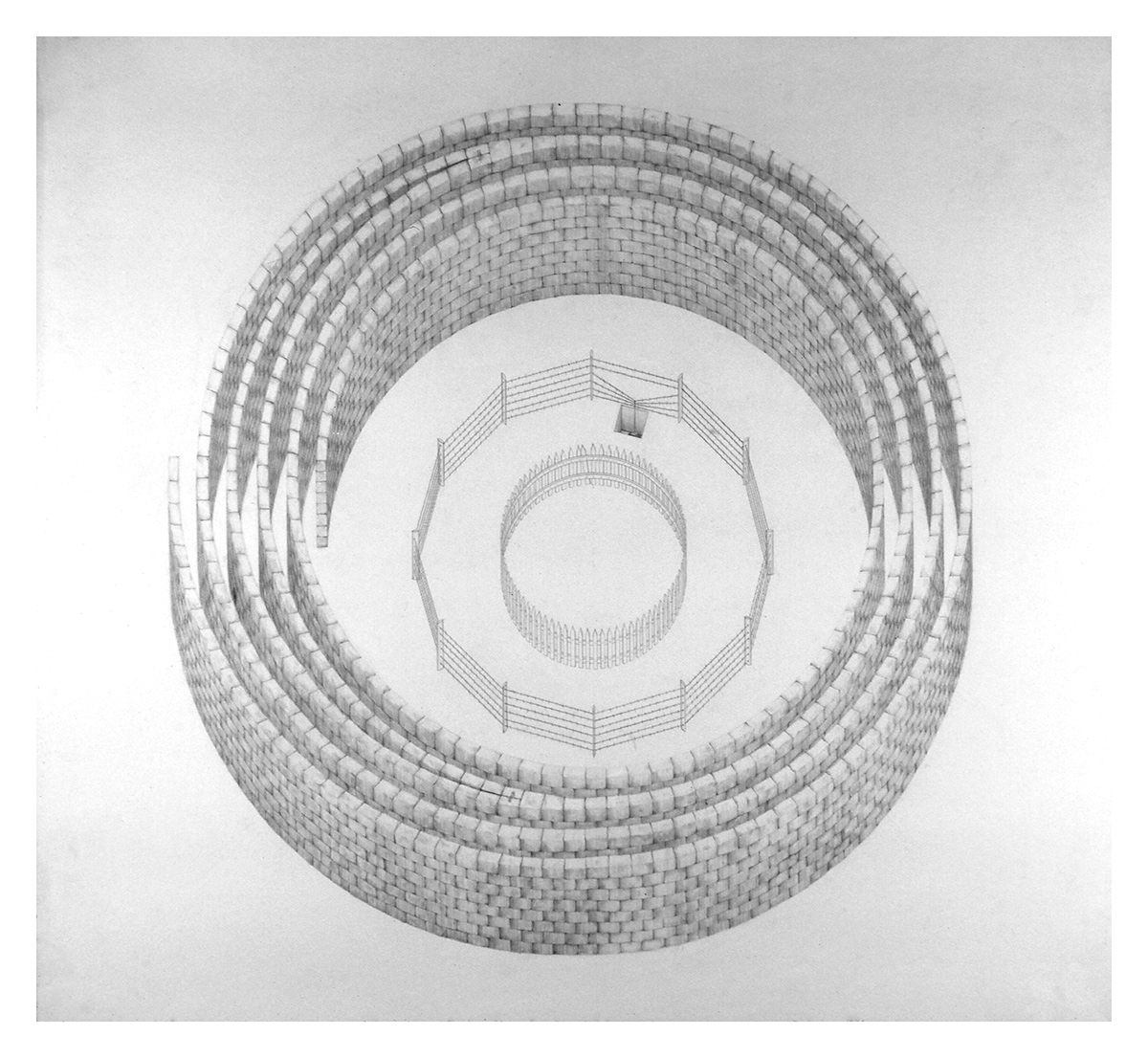

Every 20th-century shift in architectural tastes is recorded in the archives, as teachers encouraged students to experiment with forms and materials. By the 1960s, the Cooper Union’s future starchitect Daniel Libeskind was penciling in zigzag building footprints that soon became his professional trademark on landmarks like the Jewish Museum Berlin. In the 1970s, the school’s future starchitect Liz Diller, known for collaborations at Lincoln Center and the High Line, handed her professors some enigmatic renderings of masonry walls spiraling around corrals made of picket fencing and barbed wire.

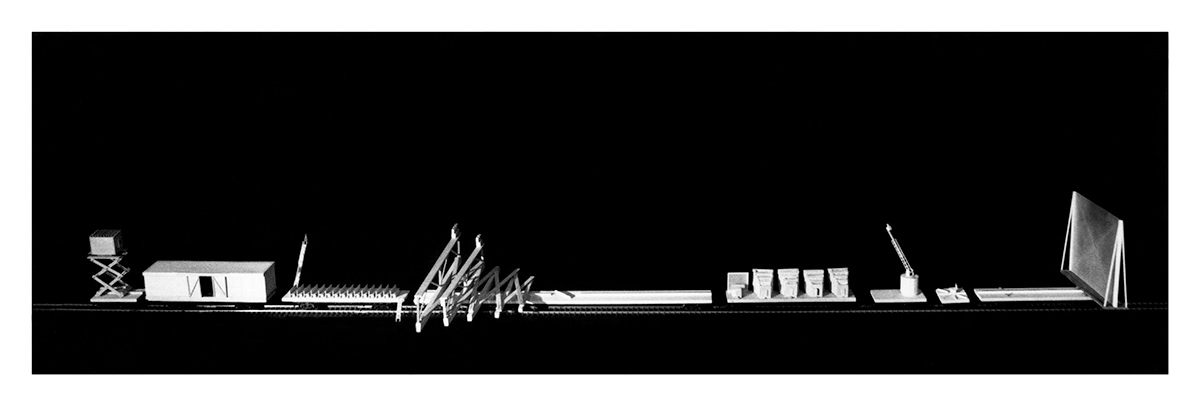

In the 1980s, another future starchitect, Laurie Hawkinson, imagined traveling around in a Cinetrain, with rail cars full of cameras, projectors, film editing equipment, and screening rooms. As the train would roll across the landscape, Hawkinson told her teachers, “Spectator becomes both actor and audience.”

Hawkinson says her Cinetrain ideas have stayed with her; they have influenced, for instance, one of her public art installations, a giant red outdoor megaphone called the Freedom of Expression National Monument. She fondly remembers her Cooper Union days of time to think: “It was such a luxury and a gift,” she says.

The prominent architect and educator Karen Bausman likewise is a little nostalgic for her formative years at the Cooper Union in the 1980s, when she proposed cantilevering a “One-Way Bridge.” Its walkway to nowhere, she wrote at the time, “cannot distinguish the difference of footsteps offered with trepidation or with an imperious gate.” The drawings, she says now, “look as fresh as the day I stopped working on them.”

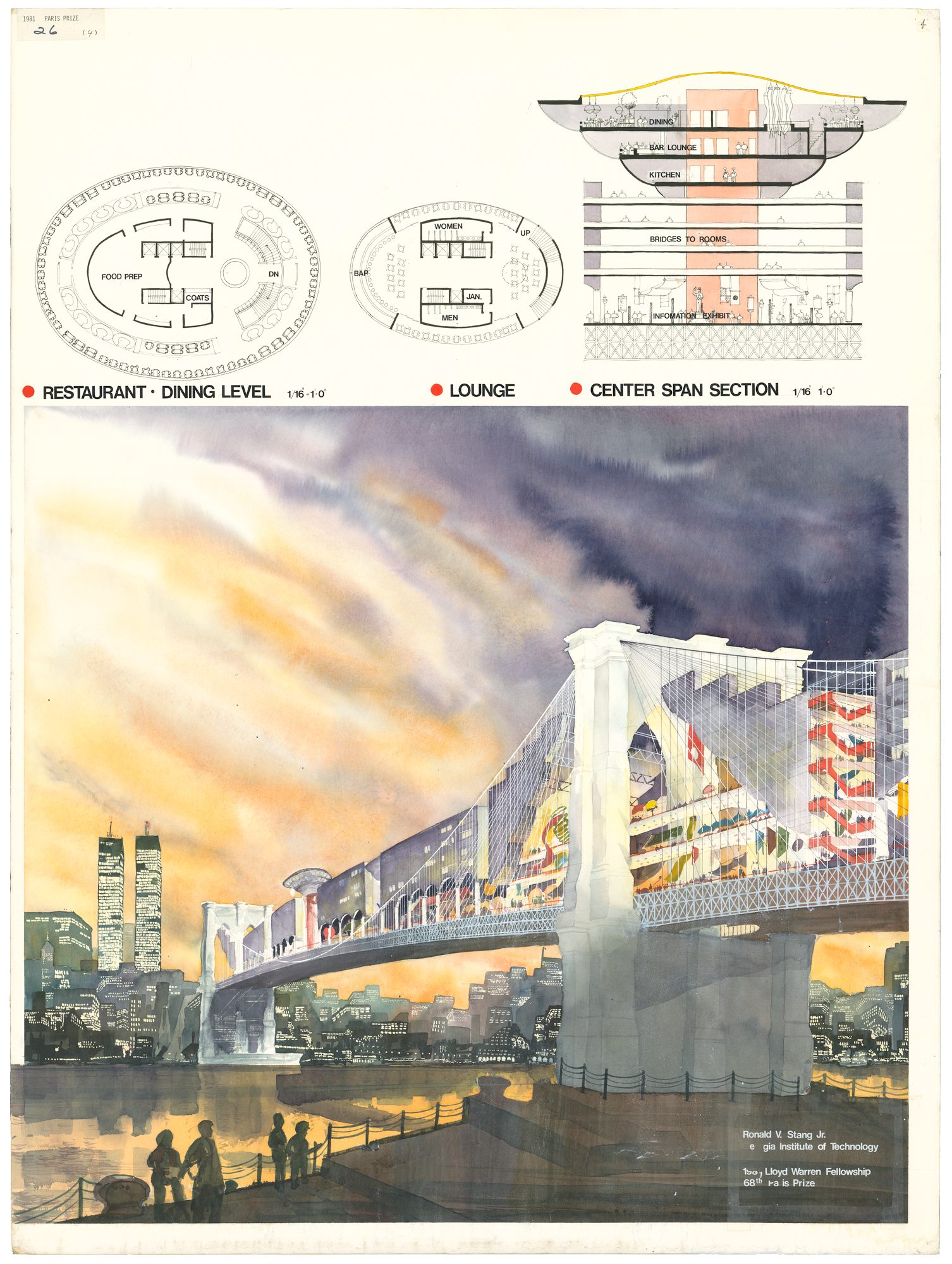

The Van Alen database contains proposals as loopy as Antarctic homes that look like overlapping Spirographs and a conversion of the Brooklyn Bridge into food stalls and apartments tucked beneath archways.

At the Cooper Union, among the most lovably impractical suggestions is Dominic Kozerski’s 1990s inhabitable metal pod that urban observers could hang from lampposts. It was meant to be used, he told his teachers, to study how “the illegible text of the inhabited city inscribes itself on the clear text of the planned legible city.” The classroom transcript shows that his professors praised him for introducing “a way, yes, a new way, another way of seeing our city.”

The database, Hillyer says, can be expanded as alumni and their loved ones come forth with memories and uncover documentation of schooldays squirreled away in storage: “I think we’re going to get a lot of blank-filling-in.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook