A Short History of Tree Shaping

People have long tried to bend trees to their will, for both practical and aesthetic reasons.

There are some ideas so compelling that humans invent them over and over again. Around the world, going back centuries, people have developed strategies to bend and coax trees into new shapes, for both practical and aesthetic purposes. For the most part, these techniques developed in isolation; only now are tree shapers learning from each other and aiming to grow trees into more ambitious forms, from buildings to furniture.

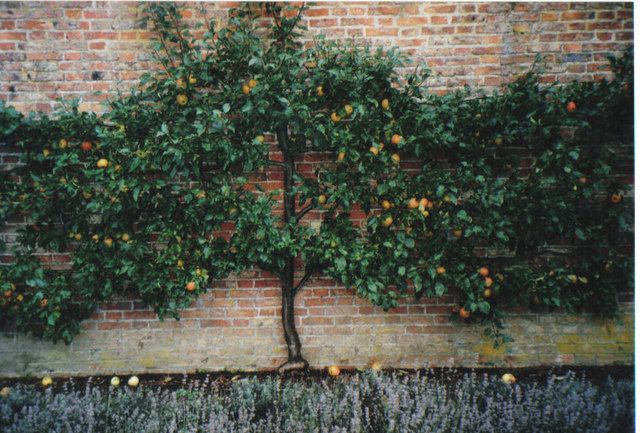

All tree shapers seem to discover the same basic principle: To train trees, it helps to mold them to existing structures. In Indonesia and northeastern India, the roots of banyan and rubber trees have been wrapped around bamboo frames to form root bridges that can withstand the fierce monsoon. In Europe, gardeners developed a technique called espalier, which involves training trees on a plane so they grow flat. They can then be guided into formal patterns and even words.

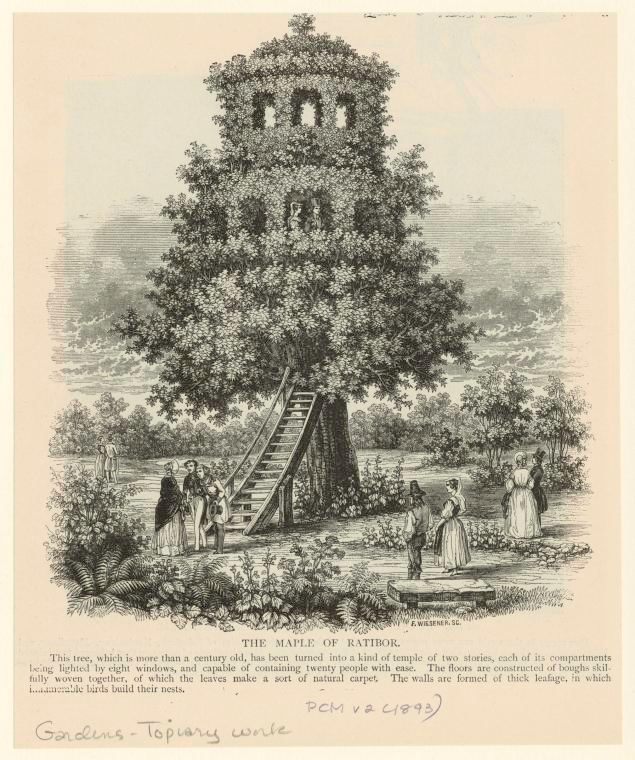

Older tree-shaping strategies often served practical purposes. By planting trees in a straight line and training their branches to weave together, a technique called pleaching, gardeners could create thick, impenetrable hedges, as well as ornamental designs. A simple type of fencing involved pulling trees into arches and grafting them together. But tree shaping often has fantastical element to it. For instance, there was a mysterious tree in Italy, the Maple of Ratibor, that took the form of a house.

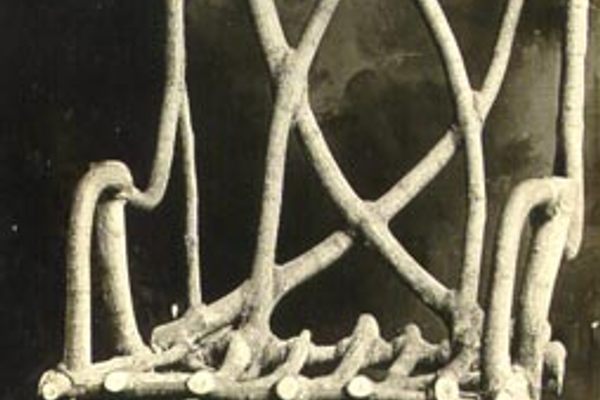

In the 20th century, a few inventive individuals independently imagined new ways to shape trees. In the early 1900s, John Krubsack, a banker in Wisconsin, planted 32 box elder trees in his backyard, with the intent of growing a chair stronger than any that could be made by a carpenter. It took him 11 years to bend, graft, and grow the trees together into a magnificent piece of furniture. In the 1920s, Axel Erlandson, a California farmer, began experimenting with shaping trees into archways, geometric shapes, and other designs no one had imagined trees could make. Around the same time, Arthur Wiechula, a German engineer, outlined fanciful, detailed ideas for growing whole houses from trees. His actual efforts were less successful, but did lead to the construction of at least a few fences made from pleached, grafted trees.

In more recent decades, tree shapers, including Richard Reames in the United States and Konstantin Kirsch in Germany, have worked to learn and further these techniques to grow designs, useful objects, and buildings, as Reames details in his book Arborsculpture. In Australia, Peter Cook and Becky Northey, the founders of Pooktre, refined their own techniques for shaping trees into figures of people, as well as chairs and mirror frames. A couple of tree shapers have also had some success with using trees to regularly produce stools and chairs—Christopher Cattle in England grows stools and Bernhard Schmid in Germany creates chairs. There are also tree shapers in Israel and in Thailand, where Nirandr Boonnetr is pursuing the art.

Still others have worked to train trees to more architectural ends. Researchers in Germany are working to refine “Baubotanik” techniques that could allow the construction of towers and other buildings from living trees, while the artist Marcel Kalberer uses willow trees to form living domes. In America, Bonnie Gale has been working on living willow structures that serve as practical and ornamental features in gardens and other designed landscapes.

As compelling and beautiful as these works can be, they can also be frustrating and difficult to create. Many tree shapers have had the experience of showing their work to horticultural experts and being told that what they’ve accomplished shouldn’t be possible. They’re asking trees to act in ways they normally wouldn’t. They’re grappling with living things that die or grow in ways that make the most sense to a tree—not a person. A design that looks good on paper can be impossible to execute.

“You’re dealing with unpredictable natural forces,” says Gale. “It can be a humbling experience.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook