In the Streets of Argentina Lie Hidden Memorials to Disappeared People

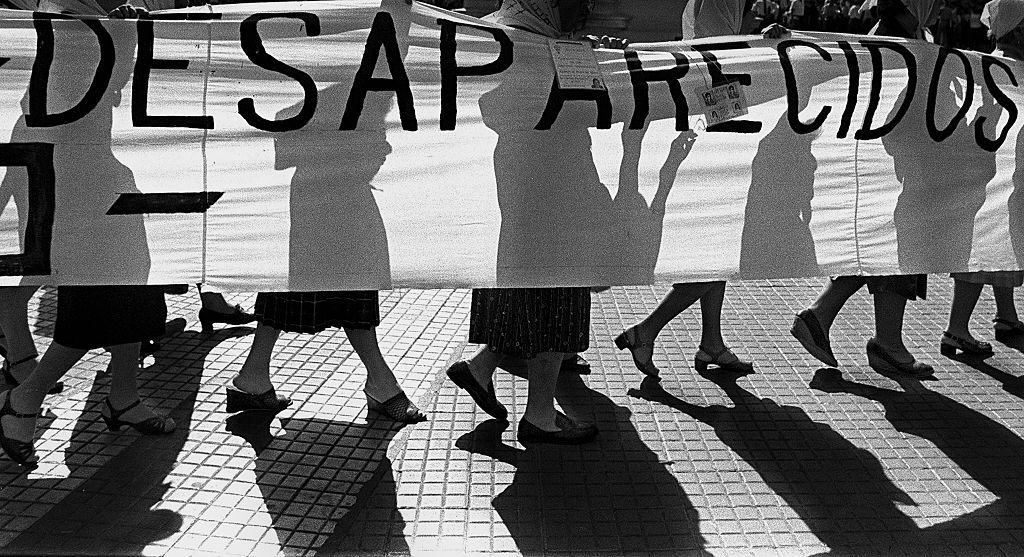

They pay tribute to those lost during a period of state terrorism.

-

The memorial tile for Emilio de Lorenzo. Sam Harrison

On August 25, 1978, the soldiers came for Emilio de Lorenzo. It wasn’t entirely a surprise: two years earlier a military dictatorship had staged a coup and taken control of Argentina. As a social activist, and a member of the leftist groups Juventud Peronista and the Montoneros, De Lorenzo knew his politics put him at odds with the dictatorship. He and his wife Eva, then seven months pregnant, had moved into a different house to avoid detection. Only their mothers knew where they were.

But on August 25, the military found them and took them to the Olimpo, a clandestine detention center. Emiliano, their two-year-old son, had to be left behind. “His grandparents will raise him well,” said the military.

Eva was released a few days later. She spoke with Emilio one more time in detention. His face was uncovered, a sign that the military wasn’t afraid of what he would witness. He wouldn’t be going anywhere to tell tales. After that, he was never seen again.

Exactly 40 years later, de Lorenzo is returning to Parque Chacabuco, the neighborhood in Buenos Aires where he was born—in a way. On a bright, windy winter day, his friends, family and fellow social activists have gathered together to place a tile in his memory in the sidewalk outside the house where he was born, nearly 71 years before.

The tile stands out against the grey sidewalk. It has white letters on a brick-red background, embedded with a few colorful pieces of ceramic and a small token with the logo of San Lorenzo, Emilio’s favorite football team. It is one of around 1,700 tiles that have been embedded around the city, each commemorating one of the up to 30,000 people who were “disappeared” by the military dictatorship that controlled Argentina between 1976 and 1983.

The tiles are created by Barrios X (para) la Memoria y Justicia, or Neighborhoods for Memory and Justice, a grassroots collection of neighborhood organizations dedicated to the memory of the disappeared. They placed the first sidewalk tiles in 2006, the 30th anniversary of the start of the military dictatorship. “For us the tiles were the symbol that this is where they walked … they left their footprints on the city streets,” says Pablo Salazar, a member of Pompeya no Olvida (Pompeya doesn’t forget), one of the neighborhood organizations that together form Neighborhoods for Justice and Memory.

Each tile follows the same format. De Lorenzo’s tile, white letters on a reddish background, reads:

Here was born and lived

Emilio J. de Lorenzo

Social Activist

Detained Disappeared

25 - 08 - 78

By State Terrorism

Neighborhoods for Memory and Justice

“The tiles are personalized to move away from talking about ‘30,000 people,’ so that they don’t remain anonymous,” says Luz Marina Martinez, another member of Neighborhoods for Memory and Justice. “The idea is that here is where this person lived, here is where they worked, here is where they studied. We want each neighborhood to learn about the compañeros that were detained, disappeared or assassinated by state terrorism.”

Between 1976 and 1983, thousands of people in Argentina were kidnapped by the military government, locked in secret detention centers, and tortured. The dictatorship targeted anyone it believed posed a threat to it or disagreed with its political ideology, including guerrillas and political activists, student activists, union leaders, teachers, socialists, communists, and journalists. Ex-military officer Adolfo Scilingo has described “death flights” in which he and others flew with victims over the La Plata River or Atlantic Ocean and “disappeared” them into the water, making their deaths untraceable. Like De Lorenzo’s family, most of the disappeareds’ loved ones will never be certain what had happened to the sons, the mothers, the friends who never came out from clandestine detention.

De Lorenzo’s sons—Emiliano, who was 2 years old when his dad disappeared, and Leo, who was still in his mother’s womb and never got to meet his father—are both political and social activists. His nephew Javier Andrade is currently a Deputy for the City of Buenos Aires.

At his memorial service, they talk about his love of Coca-Cola and San Lorenzo, the local football team. How he loved to drive, how much he loved his mother’s tortilla de papas. But most of all they talk about his idealism, his political activism, his belief in creating a better world.

“Emilio was so good. Too good,” Nora de Lorenzo, his sister, tells me. “He was very loved.” She wishes her mother could have seen his memorial tile. “At least this way you have something you can come and look at. Otherwise you don’t have anywhere to go. He’s not there! He’s disappeared. He’s not there.”

The tiles started in the city of Buenos Aires, but over the last few years, volunteers have been traveling all over Argentina to teach organizations how to create memorial tiles in their own cities. Tiles now appear in the Argentine provinces of Catamarca, La Rioja, Córdoba, Santa Fe, Jujuy, and beyond.

In addition to the sidewalk tiles embedded around the city, the Neighborhoods for Justice and Memory have also published three books about the disappeared. Unlike the tiles, the books dive deeper into who each of these people were and tries to give a bigger picture of their short lives. Their third book, Baldosas Sin Fronteras (Tiles Without Borders) was published earlier this year.

The Neighborhoods for Memory and Justice avoid working with the government and prefer to keep their organization grassroots. “We prefer to continue this way, from the bottom up, without ties to the government. Because working with the government forces you to be represented by it, to identify with it,” says Salazar.

Critics have accused the current president, Mauricio Macri, of not doing enough to honor the legacy of the disappeared. In interviews, Macri has insinuated that there were fewer than 30,000 disappeared people (something many Argentines find egregious, given how the dictatorship tried to erase its victims). “They don’t want to work on this topic,” says Salazar, referring to the current administration. “And we are convinced that we have to keep working. We have to keep the memory alive, we have to bring these compañeros out of the past, into the present.”

Of the estimated 30,000 disappeared, only 1,700 tiles have been laid down so far. The Neighborhoods for Memory still has much left to do.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook