Ice Age Australia Had Giant, Clawed, Swole Marsupials in Its Trees

Something like a koala, except the size of a rhino.

Thousands of years ago, the inland region of eastern Australia was a far cry from the sere place it is today. During the Ice Age, this part of the Southern Hemisphere hosted its own array of big charismatic creatures—answers to the woolly mammoths and saber-toothed cats up north—some of which roamed the then-forested regions of Queensland and Victoria. In a country famous today for its curious and sometimes venomous fauna, Australia’s prehistoric menagerie has proven just as weird, if not weirder, according to a new paper in the journal PLOS One.

“These were strange beasts unlike anything we see today,” says Julien Louys, a paleontologist at Griffith University, who reviewed the study. “The closest [relatives] would probably be wombats and koalas, but that’s a little like saying that a sheep is comparable to a giraffe.”

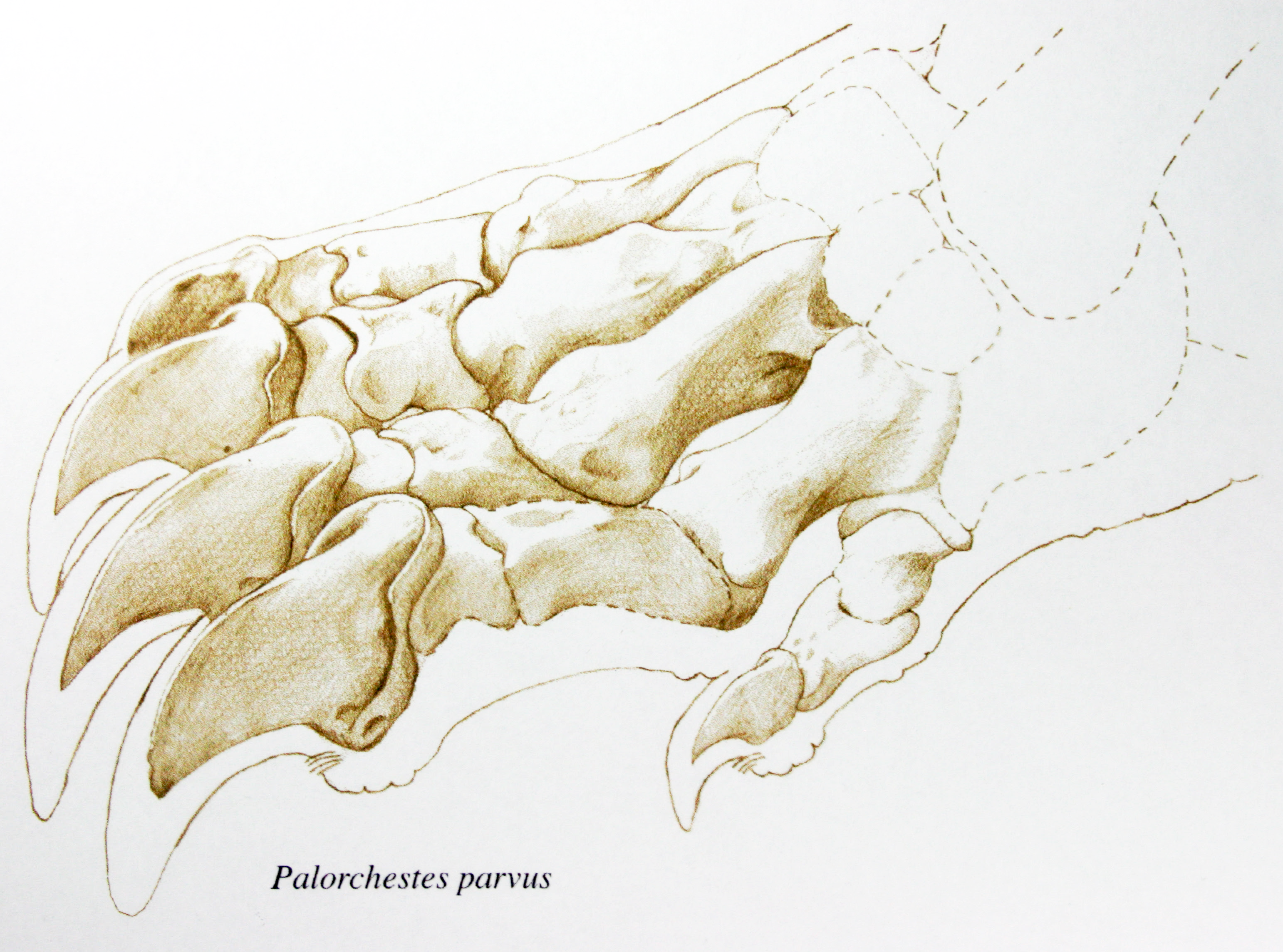

The research, involving Monash University and Museums Victoria, reveals an obscure family of extinct mega-marsupials called Palorchestidae. First identified among thousands of other bones in rich Ice Age menagerie of Victoria Fossil Cave, these creatures lived during the Miocene and Pleistocene periods (recently, as deep time goes). In describing the animals, different researchers compared the palorchestids to wombats, echidnas, tapirs, even the long-extinct giant ground sloth. They’re a little hard to picture.

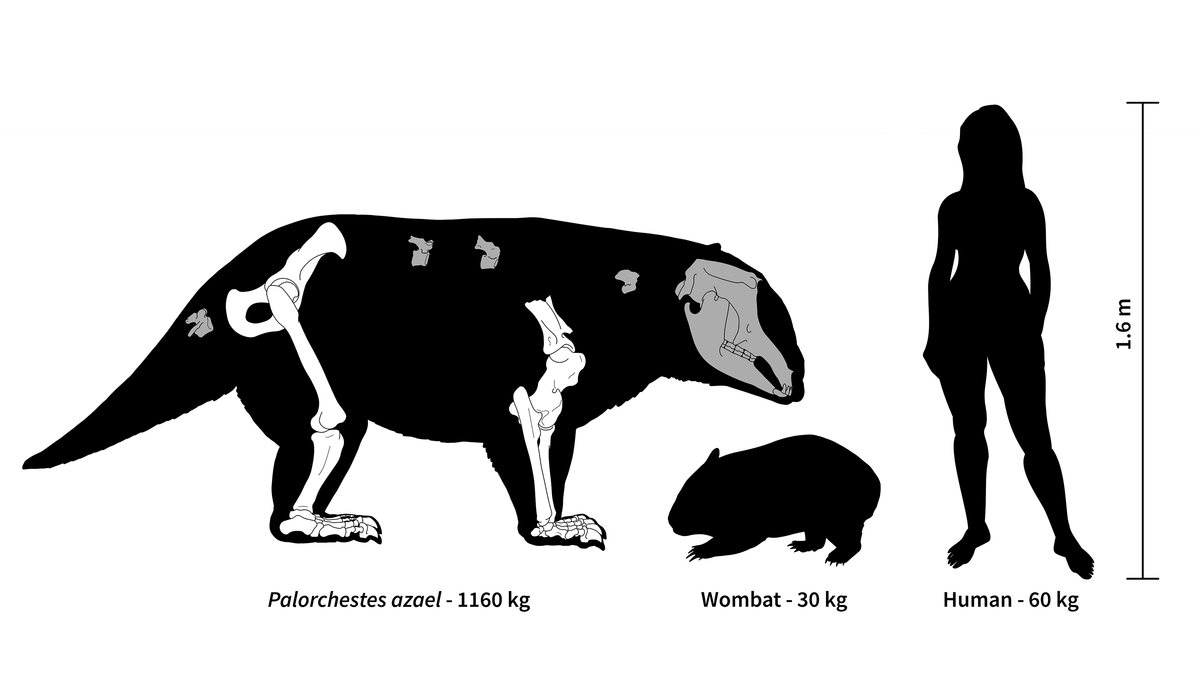

“They were pouched mammals with a long pointed face, extensible tongue, and tiny eyes,” says Hazel Richards, a doctoral student at Monash University studying marsupial evolution, and lead author of the paper. “Their bodies were front-loaded, with hugely muscled forelimbs and comparatively slender hindquarters, with robust hands and feet equipped with sharp, hooked claws bigger than a grizzly bear’s.”

Matthew McCurry, the paleontology curator at the Australian Museum, says that “some of the weirdest features” of the animals were their forelimbs. The elbows of Palorchestes azael, the largest of the three extinct marsupials examined in the study, were locked at an obtuse angle at all times, as if reaching out for a handshake, relegating arm flexibility to the animal’s shoulders, and providing some information about how the animal moved and accessed food.

It sounds a bit like putting together mismatched parts, but it amounts to something like an anteater or tapir, except out of balance—burly in front and sleek in the back—and much, much larger. Some palorchestids weighed over a ton, but in spite of their massive size, Richards speculates that some of them weren’t ground-bound.

“We suspect they were more likely to be using their claws to cling to tree trunks and use powerful shoulder muscles to pull themselves up,” says Richards, “so they could get their long tongue and nipping incisors closer to foliage higher up off the ground.” Watch out below.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook