A Japanese Sculptor’s Tribute to Wild Rice Covers an Australian Floodplain

Mitsuaki Tanabe’s untimely death spurred his son to finish his last work.

Takamitsu Tanabe wants to take a walk. Meeting in the suburbs of Yokohama, a city south of Tokyo, we make our way to the Matsunokawa Greenway, a trail that runs through the town. The path is unkempt, with native trees and grasses sprawling in tangled tufts across the walkway. It’s deliberate, explains Takamitsu, who goes by Taka. He points out that the snarl supports birds and insects.

The path was established more than 30 years ago by Taka’s parents. The Tanabe family has lived in this area for 400 years, and over the generations, housing developments gradually encroached on the Matsuno River. The river became increasingly polluted, so the Tanabes worked with the city of Yokohama to establish the Greenway around it.

Taka and I come to an enormous steel bird’s head, its beak pointed towards the sky. It was made by Taka’s late father, the sculptor Mitsuaki Tanabe. I wade through the tall grass to get a better look, and seeds stick to my boots. A brown-and-white bird swoops down, and the grass quivers as it pecks at something in the brush. “Birds are a kind of indicator because they’re at the top of the ecosystem,” says Taka. “If the ground condition is good, with a lot of plants and insects, there are a lot of birds.” Down the path, we come to another sculpture by Mitsuaki, this one a steel lizard at the side of the path. The words “WILD CRISIS” are written on its legs.

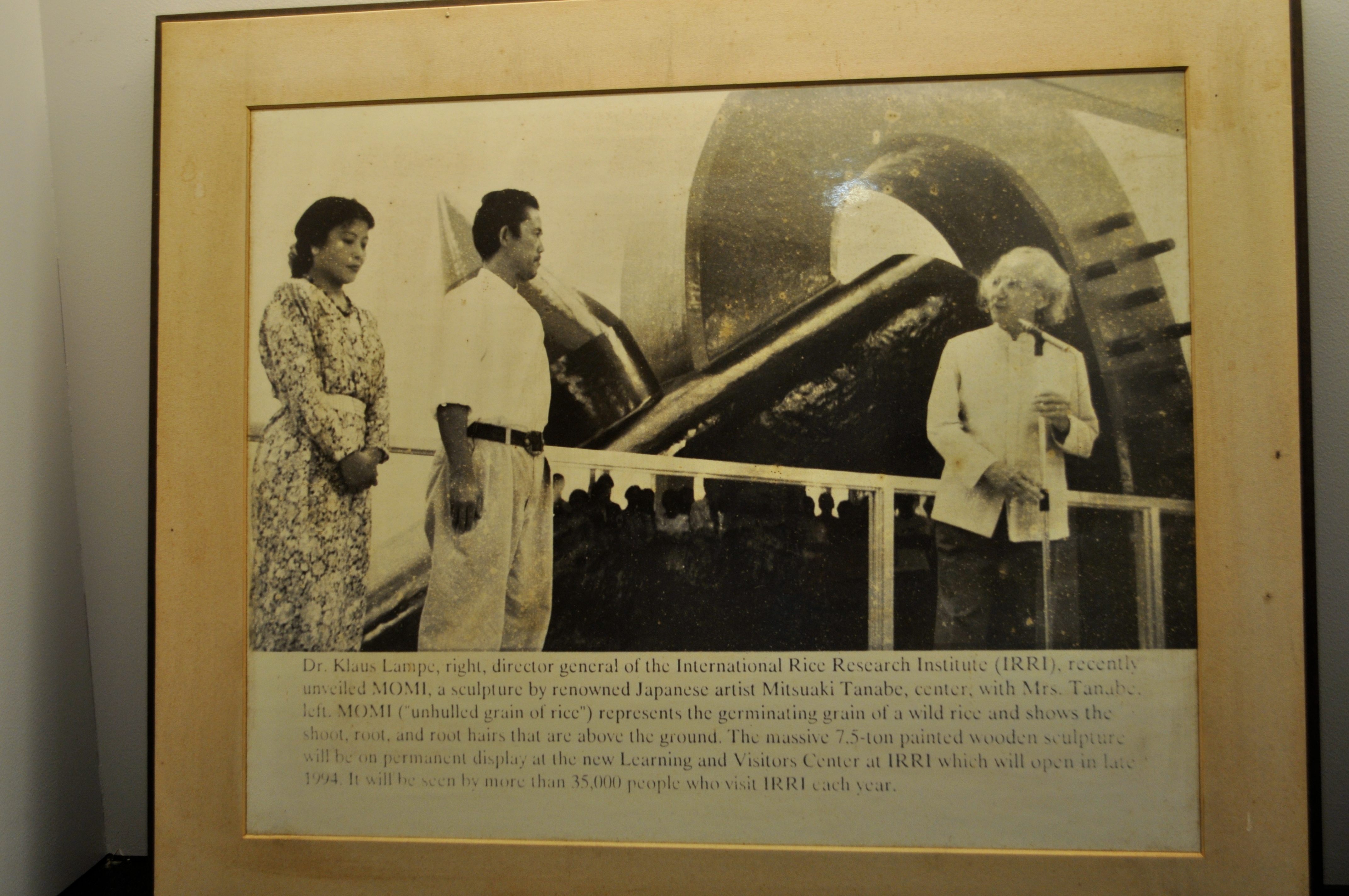

The crisis facing the world’s biodiversity was the subject of most of Mitsuaki’s work. His sculptures depicting wild seeds can be found all over the world, from Thailand to Italy. But Mitsuaki was especially passionate about wild rice. One of his wild rice sculptures is installed at the Global Seed Vault in Svalbard, Norway.

Attempting to explain his father’s fascination with wild rice, Taka notes that “70 to 80 percent of the world’s people eat rice as a main staple. It’s a precious food.” Because wild rice isn’t cultivated, it’s largely ignored. Yet wild rice holds the blueprint for modern cultivated rice strains.

“Ancestor species of our most important crops are of significant value as a genetic resource to improve the characteristics of our crops,” says Dr. Greg Leach, the former chief botanist of Australia’s Northern Territory. “They may well hold attributes of disease resistance, drought tolerance, and salinity tolerance, which can adapt our crops to changing conditions.” And of course, rice is a mainstay in Japan.

Mitsuaki graduated with a degree in sculpture from Tama Art University in 1961, then trained for a time under the Japanese-American sculptor Isamu Noguchi. Over the following decades, Mitsuaki developed his craft: traveling, working on public projects, and carving out his own space in the art world. He worked in Australia in the 1990s, and in the early 2000s, he dreamed up a new project.

“Tanabe-san had heard about wild rice growing in northern Australia and was keen to see this for himself,” says Leach. He arranged for Mitsuaki to travel to the UNESCO World Heritage-listed floodplains outside of the city of Darwin. “He was totally blown away at the extent of wild rice, as elsewhere in the world wild rice has been almost wiped out due to development of floodplain areas,” Leach says.

There, Mitsuaki decided to create one of his wild rice sculptures, which he called “Momi,” in order to raise awareness of the Northern Territory’s wild rice varieties (which include Oryza officinalis, Oryza rufipogon, Oryza meridionalis, and Oryza australiensis) and to support their conservation. “His main medium was stainless steel, and we were initially a little perturbed about having a large stainless steel sculpture in the wetlands,” says Leach. “However, when Tanabe saw the beautiful granite boulders around Mount Bundey, he sought approval to use these as his medium for creating his sculptures.”

Mitsuaki received support from the Australian Embassy and the government of the Northern Territory, as well as permission from the aboriginal landowners. “[Mitsuaki was] taking a fantastic passion from Japan and applying it to something that most Australians aren’t even aware of, wild rice,” says Michael Hoy, Public Affairs counsellor at the Australian Embassy in Japan.

Mitsuaki went back and forth between Japan and Australia for 10 years, carving insects and lizards into the granite boulders, and a 269-foot-long wild rice strand into the floodplain itself. He visited in the dry season in order to avoid the area’s poisonous creatures and spent a month per year carving, sometimes with the help of other sculptors. “Our floodplains are far from pristine, and face a number of threats such as weeds, feral herbivores, and sea level rise,” says Leach. “The efforts of a Japanese sculptor have served to highlight the valuable resource we have in wild rice, as it is a key species in the ecology of the floodplains.”

“It sometimes takes an outside perspective to awaken us to what we have,” he adds.

But in 2014, Mitsuaki had a heart attack and collapsed. Within a year, he passed away. His work in northern Australia was left unfinished.

He had so loved working on the project, reminisce Taka and his mother Misayo. “He was very steadfast and put a lot of effort into it,” says Misayo. “He was a taciturn person, but if he started talking about sculpture, he was incredible. He would talk all night.” Bringing attention to issues of biodiversity was his life’s work. “He thought a lot about how he could be of use as a human being,” explains Misayo. Both Taka and Misayo thought he would have wanted his epic Australian endeavor to be completed.

At the time of his death, says Leach, “he already had a significant body of work spreading over quite an area. A few items were unfinished, but the site already achieved his vision as a statement on the significance of wild rice and the international conservation value of our wetlands.” Yet the huge strand of wild rice, which Mitsuaki called “Momi-2010,” was not quite completed, and neither was the uncarved outline of a beetle nearby.

Taka decided to finish his father’s work. While not a sculptor himself (he’s the curator of the Hiyoshi no Mori museum, which is dedicated to both his father’s art and preserving the ancestral Tanabe home), he enlisted help from artists who had known Mitsuaki, as well as from the Australia-Japan Foundation.

“With Mitsuaki’s sculptures, we wanted to convey the importance of wild rice to future generations,” says Kazuhisa Aketa, who helped to complete the unfinished “Momi-2010” sculpture. “The wild rice of the Northern Territory, and rice, a Japanese staple food, may save the future of the earth,” he says. “And as a sculptor, I thought the work shouldn’t go unfinished. This special project took more than 10 years, and I thought it was very important to complete it.”

The “Australian In-Situ Wild Rice Conservation Project” was finally finished in 2016. In a region with plenty of wilderness, it has the potential to become a powerful symbol of conservation. “The project is significant to northern Australia for a number of reasons,” says Leach. “We now have the artwork of an internationally recognized sculptor in a dramatic outdoor setting on the approach to a World-Heritage listed area in Kakadu National Park.”

It also helps foster the relationship between Japan and Australia. Hoy says that many older Australians associate Darwin with its bombing by Japan in World War II. “I think for Australians traveling through the region, finding that a Japanese sculptor has come to the Northern Territory has helped,” he says. Now, carved into the floodplain forever, there’s a physical representation of the connection between the two countries, and “how far we’ve come,” notes Hoy.

Mitsuaki used art to raise awareness of the natural world, and both his wife and son hope that his message will continue to resonate, even after his death. “Do you know the term shin-zen-bi?” asks Misayo. (It means “truth, goodness, and beauty” in Japanese.) “We need beauty during tough times. Looking at beauty gives us back our energy.”

The Tanabes hope that some of that energy can go towards the fight for biodiversity, both for the sake of humanity and the natural world. Mitsuaki saw seeds as the key to that fight. After all, says Taka, “seeds have infinity power.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook