A 17th-Century Portrait of a Glamorous Bearded Woman

Who was Barbara van Beck?

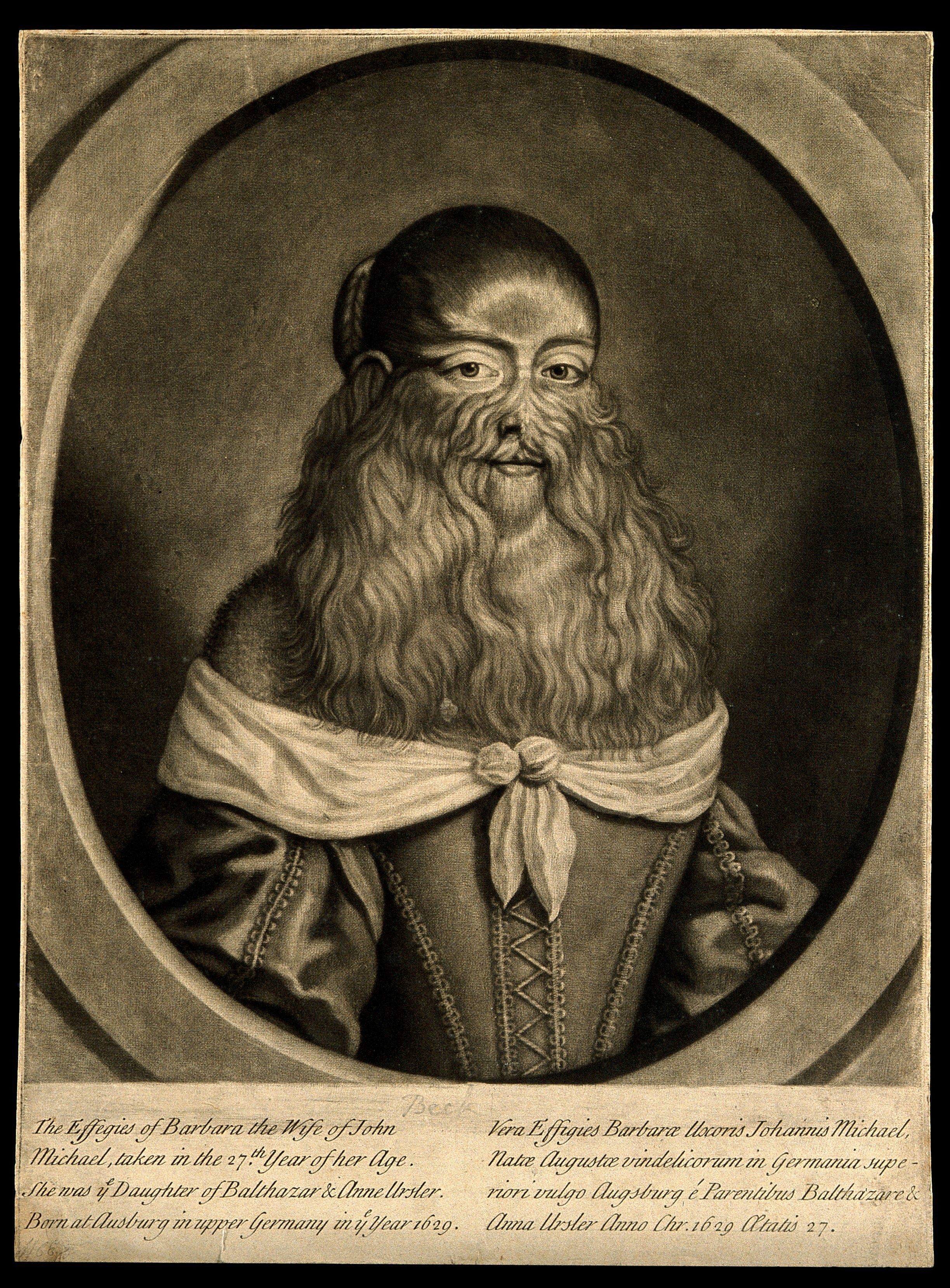

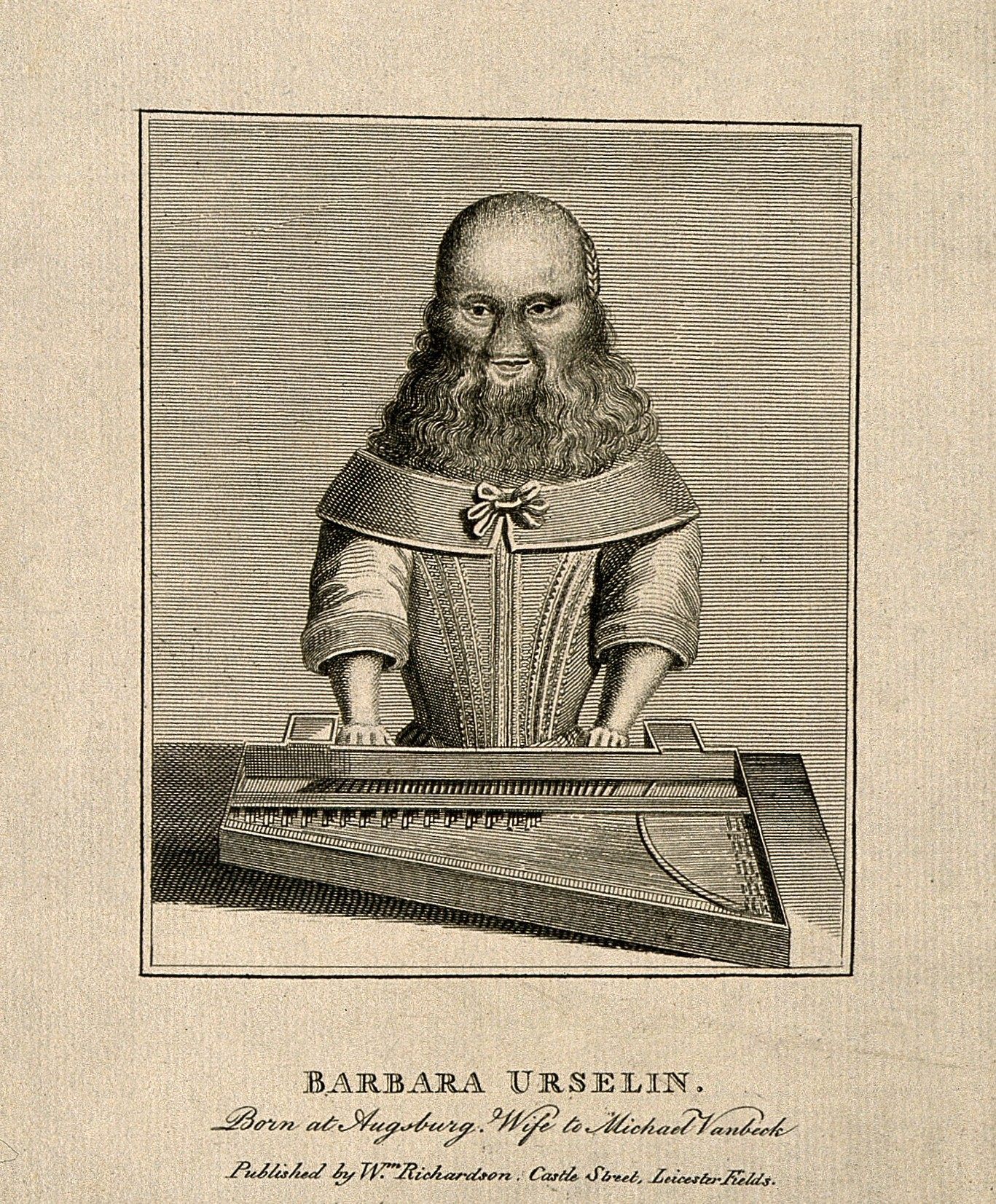

Even as a tiny child, Barbara van Beck had a great cascading beard. It began somewhere around her eyebrows and finished beneath her chin, covering her temples, cheeks and nose with a thick coating of luxuriant dark blonde hair. Born in Bavaria in 1629, she spent some 30 years on tour across Europe as part of a high-end traveling show, which also included a famous rope-dancer who performed perilous stunts while blindfolded.

It’s tempting to assume that a woman as striking as van Beck would have been destined to a difficult life, or trotted out in these shows as some kind of monster. But the evidence suggests that her decades of touring afforded her celebrity status, financial security, and an expansive education that encompassed learning several different languages and the harpsichord. This week, the Wellcome Collection in London acquired a rare depiction of her in oil paint, which they will be exhibiting from early next year.

Researchers believe van Beck had a very rare congenital condition known as hypertrichosis or Ambras Syndrome, the condition that may have inspired the Star Wars character Chewbacca. There are many famous accounts of people with the condition, while modern images show near-identical hair-growth patterns to van Beck’s. This, and an element of pathos to the finely detailed portrait in oils, suggests that it was probably painted from life, and perhaps by an Italian artist while she was traveling through Rome or Milan in the late 1640s.

“We know that Barbara van Beck was a successful public figure, renowned internationally, and that she turned this condition to her advantage,” Angela McShane, Research Development Manager from the Wellcome Collection, said in a statement. In a 1657 diary entry, the English writer John Evelyn described seeing her: “Her very eyebrows were combed upward, and all her forehead as thick and even as grows on any woman’s head, neatly dressed; a very long lock of hair out of each ear; she had also a most prolix beard, and moustachios, with long locks growing on the middle of her nose, like an Iceland dog exactly, the color of a bright brown, fine as well-dressed flax.” (This was a kind of lap-dog popular in the period.) Other accounts mention being “satisfied” that she was truly a woman, which may have entailed her exposing herself as part of the show.

Van Beck’s personal life was very much tied up with her professional life. (It’s not known when she died or under what circumstances.) She married a Dutchman, Johan Michael van Beck, who would later become her manager. More cynical 17th-century accounts claim that he married her only “to make a shew of her”, though they did apparently have a child together, who did not inherit her genetic condition.

Portraits show van Beck in glamorous silk gowns, in poses befitting a woman from the upper classes. These gowns, in addition to having been very expensive, are in the latest fashions of the time, and emphasize her femininity without seeking to ridicule or fetishize her. “This is a beautifully executed high-status painting,” McShane told the Guardian. “She is not portrayed as a freak as the Victorians would have described her—as I often say when lecturing, you can blame the Victorians for most things—but as a woman with great self-possession and presence, painted at a time when she would have been viewed, as Evelyn saw her, as wonderful, a natural wonder.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook