It’s a sweltering July morning and stein collector extraordinaire George Adams is enjoying a glass of Yuengling from the kegerator. Sitting at the workbench of his home-museum, Steins Unlimited, in Pamplin, Virginia, the 79-year-old attempts to match a “nice, somewhat rare” 18th-century earthenware stein with a period-correct pewter top.

“This one came out of a box of crap I bought from an estate auction up in Maryland,” he says with a chuckle. Tall with a sweep of silver-white hair, Adams delights in finding new treasures—especially at bargain prices. Lining the table are a number of Old Style brewery steins from the early 1980s. Though they aren’t very rare, to get the beauty, he had to buy the whole lot.

The size of a small tankard, the piece in question features a beautifully speckled cobalt glazing and is etched with ornate patterns of leaves and flowers. Adams says he can get an idea of its age with a quick glance.

“The gray clay tells me the materials were sourced from quarries in the Westerwald, which is a mountain range outside of Höhr-Grenzhausen, Germany,” he explains. The etching is of a type that came into vogue in the early 18th century. The coloration and orange-peel-like speckling—produced by “throwing salt into the kiln once the clay got red-hot”—point to techniques used by regional manufacturers between 1720 and 1800. Lastly, there’s the handle: “See that circle shape at the bottom there?” he asks. “Those didn’t appear on Westerwald steins until about 1740 and were replaced soon thereafter.”

Fitted with a lid, Adams dates the stein between 1740-1750 and places it among an array of similarly aged German vessels. With more than 10,000 steins organized by country, manufacturer, artistic style, and historical epoch, Steins Unlimited is home to one of the world’s largest and most preeminent collections.

Adams has been stockpiling beer vessels for more than 50 years—an obsession that dates to early childhood. “My grandfather was a first-generation immigrant from Germany,” says Adams, “and brought a lot of the Old World traditions over with him.”

In Adams’s childhood home, a hand-carved wooden cup with a handle and top hung above the mantelpiece. When his mother explained that the object had belonged to his great-grandfather and was a “stein,” it took on a mythical significance. “That word was so odd; it fascinated me. I started to imagine where this ‘stein’ thing came from and what kind of world it had been a part of.”

Adams says he started collecting steins “seriously” in his early-30s. At antique shows and flea markets, if a vessel caught his eye and the price was reasonable, he’d buy it. He purchased books and guides, too, and immersed himself in steins’ 600-plus-year history.

“The word stein is a shortened form of steinzeugkrug, which is German for stoneware jug or tankard,” writes Gary Kirsner, author of The Beer Stein Book. “By common usage, however, stein has come to mean any beer container … that has a hinged lid and a handle.”

The distinctive lid was originally added to prevent plague. After the Black Death killed more than 25 million people in the 1300s, Europeans, who believed dirtiness had given rise to the plague, sought ways to be more cleanly. So when “hordes of little flies … invaded Central Europe in the early-1400s,” Kirsner says, principalities in what is now Germany, “passed laws requiring that all food and beverage containers be covered.” The common mug soon had a hinged lid with a thumb-lift.

Combined with further mandates that “beer could be brewed only from hops, cereals, yeast, and water,” and “strictly enforced regulations concerning [its] quality and transport,” Kirsner says, a golden age of beer production ensued. As average consumption rose to “about two liters per person, per day,” taverns and beer houses proliferated. By the 1500s, “everyone in Germany needed a personal drinking vessel to be proud of.”

As steins were transformed into status symbols, competition arose among manufacturers. “Renaissance artists supplied designs,” says Kirsner. Tankards were soon “decorated with family crests and historical, allegorical, and biblical scenes,” and colored glazes added. In other words, beer-drinking was accompanied by a “pleasure for the eyes.”

“The more I learned, the more I got hooked,” Adams confesses. Soon, his collection had grown into the hundreds and filled multiple rooms.

In 1980, he attended his first event as a vendor. Selling provided both a “thrill” and an “excuse to buy more.” By the mid-80s, Adams had purchased a trailer and was regularly showcasing upward of 700 antique and specialty steins. Despite working full-time as a meat inspector, he attended about 20 expos a year. By unloading 20-30 steins at each, his gross sales averaged around $25,000.

In 1994, Adams took a leave of absence from Oscar Meyer to travel to Germany. There, he apprenticed to learn the art of crafting pewter tops “by hand, the old-fashioned way.” In rural beer pubs, he witnessed stein culture first-hand.

“It was like stepping back in time,” he says. “The townsfolk all had their steins hanging on pegs above the bar. They’d come in after work and have a pint before heading home.” Sometimes whole families would gather—the kids sipping from tiny steins filled with special low-alcohol beer.

Moved, Adams quit the meat business to pursue his passion. For a decade, he toured the East Coast and Midwest, selling rare and collectible steins. While most sold for about $50, his biggest sale was around $10,000. “At my best show, I sold 150 in four days,” he boasts, grinning.

Health concerns and a floundering market forced Adams to park the operation in 2009. By then, he’d accumulated more than 9,000 rare and historically significant steins. Seeking a way to give the public access to the collection—and his knowledge—he founded the Steins Unlimited museum.

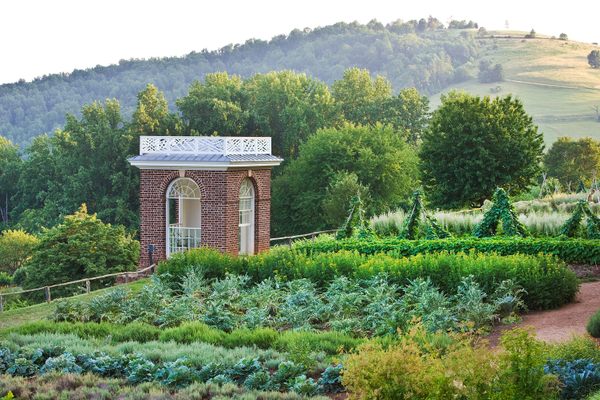

It’s an unconventional museum. Located just off U.S. Highway 460 on the periphery of a tiny 200-person hamlet, Steins Unlimited is essentially in the middle-of-nowhere. The bulk of the collection is housed in a two-room shed in Adams’s backyard, and prized artifacts are displayed in his five-bedroom brick rancher. A pull-behind trailer provides storage for overflow.

Adams has no official Facebook page or website—the museum advertises its presence by way of two hand-painted signs: One hanging from the mailbox; the other rising from a road-fronting garden. Still, Adams says as many as 1,500 people visit each year. And those that do experience a fantastic treat.

Stepping inside the shed, I am greeted by a massive, 32-liter vessel. Gorgeously crafted, it stands about four feet tall, is made of porcelain, and features a Dürer-esque tavern scene in blue and white relief. Crowned by what Adams describes as a “German beer king,” the piece was part of a limited run produced in the early 1950s and was, he says, the the world’s largest stein. “A company recently produced one slightly bigger,” he jokes, “so now it’s the world’s second-largest.”

The colossus is surrounded by more than 3,000 European steins. Starting on the right-hand side of the room at the kegerator, a tour begins with the question: “Would you like a glass of America’s oldest beer?” If so, Adams is happy to pour you a Yuengling. (Pints and admission are free, though donations are welcome.)

Proceeding counter-clockwise, he launches into an account of the history of the stein. Selecting examples from the floor-to-ceiling shelves, he uses vessels as illustrations. We peruse offerings from the 14th to 19th century, pausing to examine technical details, family crests, and scenes ranging from bawdy to religious.

We dwell on the superior craftsmanship of 1850-1910, the “golden period of steins,” when “German laborers were willing to spend as much as a week’s pay” on a personalized vessel. Sometimes, guilds awarded members with “occupational steins” commemorating achievements or mastery. At this point, Adams retrieves a stein with an image of a uniformed constable ambling along the hilly streets of an idealized village.

From there, it’s on to an exhibit called “The War Years.” Starting with the unification of Germany under Otto Von Bismarck, it continues through World War I and concludes with an eerie collection of Third Reich materials.

“Notice how the symbols get more and more aggressive as Hitler’s power increases,” says Adams. Indeed, featuring leaves and softly rounded tridents, Nazi steins from the 1920s look rather quaint. By the early ’30s, swastikas and iron crosses have appeared, albeit small and mostly hidden in banners. Just before the war, they became flagrant.

Other parts of the tour include a large room whose 6,000 pieces, according to Adams, represent every major U.S. brewery of the 20th century. In the house, there are dazzlingly carved wooden steins, glass steins, steins with dragons’ tails for handles, steins with portraits, and steins made of sterling silver and even lidded with gold. In his “prize room,” Adams has about 500 such vessels. Dating from 1350, he says they are all hundreds of years old, were likely made for German elites, and would have been used only as table decorations or on special occasions.

By the end of the two-hour tour, I’ve had a happy three pints.

“The funny thing is, I’ve been to Europe countless times and know bunches of collectors, but in truth, most of my stuff came from auctions where people were just trying to get rid of what they thought was a bunch of crap,” laughs Adams. “What’s that they say about treasure—one’s man’s junk is another man’s museum?”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook