The Prized Pepper That Comes From a Single New Mexican Town

But can it be grown anywhere else?

Nearly 300,000 pilgrims travel annually to Chimayó—a rural community nestled in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, about 40 minutes north of Santa Fe—to visit the town’s famed Santuario de Chimayó. They come to worship at the early-19th century, adobe church complex and perhaps take home a handful of tierra bendita (“holy earth”) from el pocito, a sacred pit adjacent to the altar. Dirt from the pit is said to have performed miracles and cured cancer, among other illnesses.

Having gratified their spiritual needs, many visitors also make a culinary pilgrimage to the El Potrero Trading Post just around the corner, where they purchase a satchel of the somewhat equally renowned, blood-red chimayó chile powder. While it may not cure cancer, it is revered by many as one of the best, if not the best, chile powders in the state.

“We sell a lot of it. It’s our biggest seller,” says El Potrero Trading Post manager, Nicolas Madrid. Madrid’s customers are willing to pay a hefty $45 per pound for the richly aromatic, respectably hot chile powder, made from ground, sun-dried chimayó peppers, just one of about two dozen or so “native” or “New Mexican landrace” chile peppers endemic to northern New Mexico. That’s roughly six times the cost of your average, mass-produced New Mexican red chile powder. The reason, say locals, has a lot to do with that same, sacred dirt in the neighboring church.

“It’s the soil,” says local farmer Crescencio “Chencho” Ochoa, owner of El Jardín de Chile de Chimayó, who supplies El Potrero with much of its chimayó chile powder. “It’s the rich soil here that gives chimayó chiles their special flavor.”

That flavor, like most, begins in the nose. A face-first inspection of a bag of chimayó chile powder summons aromas that are earthy, deep, and historic, like the smell of an old saddle. Then come flowery top notes that sing to and lightly singe the nostrils. (The pepper’s burn is caused by capsaicinoids, chemical compounds that scorch the mouth, triggering pleasure-inducing endorphins to come to the rescue—a pain-for-pleasure trade off that only humans seek out, since most mammals avoid eating chiles.)

Chimayó chile powder’s unique flavor—sweet and hot, in roughly equal measures, like a piece of Fireball candy—is why local cooks buy as much as they can get their hands on when it is available.

“Chimayó chile is one of the hardest to get,” says Florence Jaramillo, owner of Rancho de Chimayó, a widely acclaimed restaurant located in a 19th-century hacienda, where ristras—ruby red strings of dried chimayó chile peppers—hang from the roof rakes like icicles. Having grown them herself in the past, Jaramillo says that chimayós are delicate plants that require a lot of water. Like her agrarian neighbors, she looks to the amount of snow in the snow-capped Sangre de Cristos to gauge how much melt there will be in the spring to water this year’s crop of chimayós. The availability of the treasured chile means a significant difference in the flavor of her signature carne adovada, pork shoulder marinated overnight and then slow-baked for hours in a red chile sauce, made from roasted chunks of chimayó chile pepper.

Chimayo and other New Mexican landrace chiles have attracted out-of-state admirers, some of whom are growing the esteemed pepper in fertile areas—far from Chimayó’s sacred soil—to feed the hunger of chefs and chile pepper aficionados. Conservationists, too, who worry about the survival of this small, site-specific chile culture, are spreading the seeds. What’s up for debate, though, is whether landrace varieties that spread beyond New Mexico will remain the same, beloved chile.

Today, New Mexico is America’s second largest producer of chile peppers, after California. What wine is to France, so chiles are to New Mexico. The chile pepper is the official state vegetable (a lawmaker’s blunder, as chiles are actually a fruit), while New Mexico is the only state with an official question: “Red or green?” (As in which kind of chile sauce do you prefer. The diplomatic answer is “Christmas,” meaning both.) Each fall, in Santa Fe and other cities and towns across the state, the redolent smell of chiles being roasted by street vendors hangs in the air like incense.

Millions of grocery shoppers are familiar with “New Mexican chiles,” which were developed by horticulturist Fabián Garciá in the early 1900s to be less spicy for non-Hispanic tastes. He also bred the pepper for uniformity. No matter where you plant it, it remains pretty much the same chile. These mass-market chiles come from the southern half of New Mexico.

Landrace chiles such as the chimayó come from the more rugged, less-populated north, where small-scale chile farming has gone more or less unchanged for centuries. Most historians believe the Spanish introduced chiles to the region from Mexico during the late-16th century, scattering them across remote hilltop pueblos. After generations of planting and seed-saving, they adapted to the climate and geography, and eventually became a dietary staple in local Hispanic communities. Native Americans also developed a fondness for chiles, adding them to their traditional staple diet of the “three sisters” crops of beans, corn, and squash.

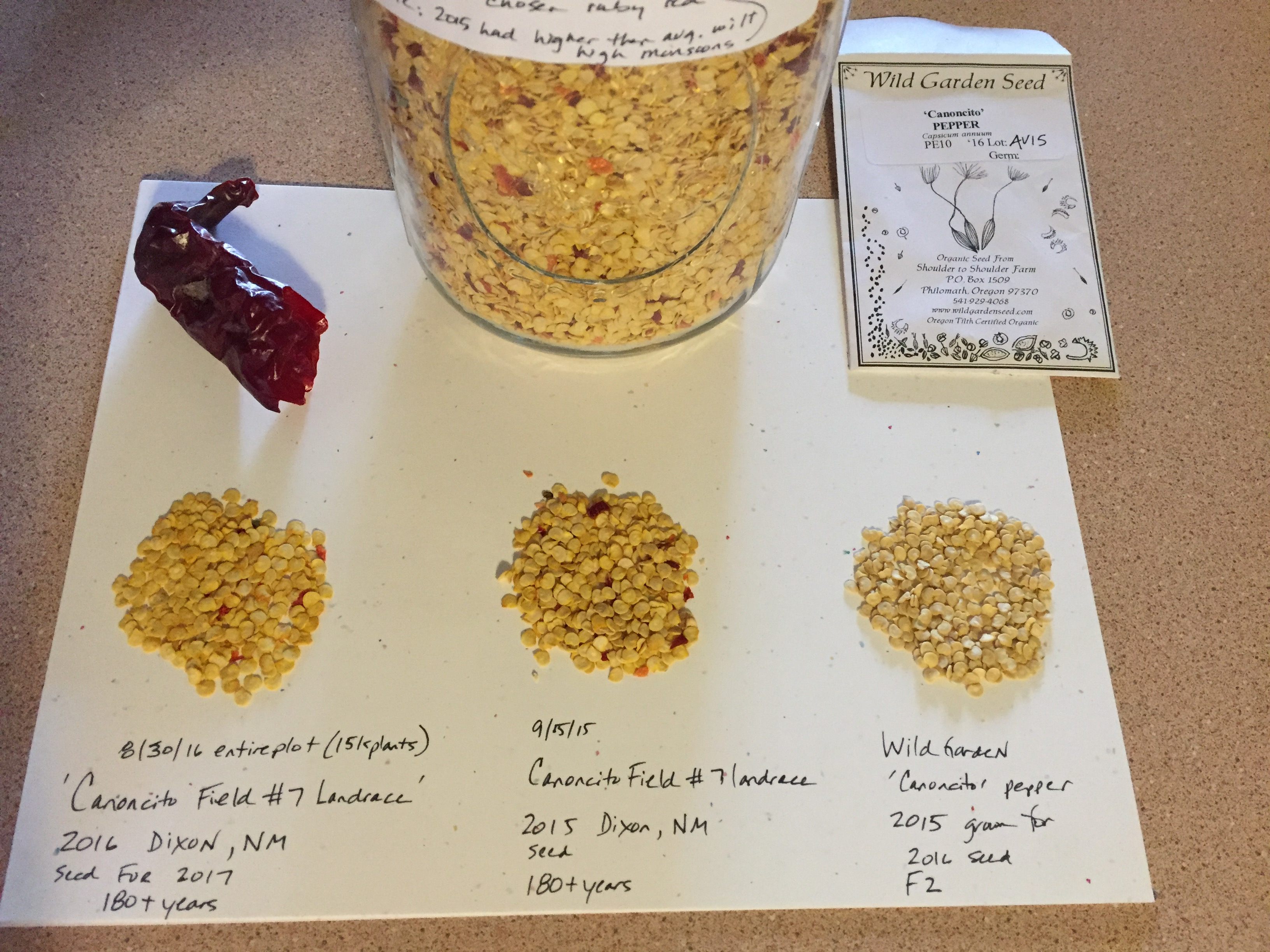

“I learned how to grow food, and preserve food, and save seeds from my grandfather,” says Margaret Campos, who traces her ancestry back to Picuris pueblo dwellers and a 16th-century Spanish adventurer from Seville. She grows landrace chiles—chimayós and gnarled, fruity velardes—on her ten and a half acre farm in Embudo. A farmer and a cook, she plans to offer classes in roasting chiles and cooking in a horno, a traditional beehive-shaped adobe oven—another import, like her ancestor, from southern Spain. The tendency to save chile seeds in jars and coffee cans, in the deep, cool recesses of north-facing rooms of adobe farm houses, and to pass them on from grandfather to father to son, was just something everybody did, says Loretta Sandoval, an organic farmer and analytical chemist who grows landrace Cañoncito chiles at Zulu’s Petals, her seven acre farm three miles east of Dixon, New Mexico, home to the state’s largest population of organic farmers.

“These chiles retain genetics that go back thousands of years, to South America. Their genetic mapping doesn’t really resemble anything from North America,” says Sandoval who, along with Campos, Ochoa, and others, is among northern New Mexico’s dedicated growers of landrace chiles.

The genetic purity of landrace chiles, Sandoval says, is what has helped them adapt and survive in the extreme weather conditions of the region, where elevations of five to six thousand feet or more make for short and precious growing seasons.

“These chiles are very cold-tolerant and bug-resistant, and come up fast to compete against fungi and bacteria in the ground. They also have long tap roots, like carrots,” says Sandoval. “I can go two to three weeks without watering them in the middle of a crazy 100-degree summer,” she adds, with no small measure of awe.

Yet for every grower like Sandoval, there are those who are abandoning the old ways of farming, potentially endangering the survival of landrace chiles in their native habitat.

“They’re declining more rapidly among the Hispanic villages up north,” says Chuck Havlik, a researcher at New Mexico State University (NMSU) who has studied the agriculture of the northern New Mexican pueblos. “A lot of the younger generation are not interested in farming. They’d rather move to the city and do something different.”

But that doesn’t mean landrace chiles have not caught on beyond the state’s borders. Since 1983, the mission of Native Seeds/SEARCH in Tucson, Arizona, has been to preserve the seeds of foods “our grandparents used to grow,” according to the organization’s mission statement. New Mexican landrace chile seeds are among the nearly 2,000 varieties of seeds in the organization’s seed bank. It further distributes up to 10 packets of free seeds annually to any tribal peoples from the Southwest, with discounts for Native Americans living outside the region.

And from California to Oregon, North Carolina to New Jersey, many green houses and mail-order outfits sell heirloom seeds, including chimayós, not to mention their powder. Aficionados warn that landrace chiles grown outside the pueblos won’t taste quite the same, as each landrace chile environment has unique soil and climatic properties that impact its flavor profile. Yet that hasn’t stopped vendors besotted with landrace chiles, such as Jim Duffy of Refining Fire Chiles in Lakeside, California, from attempting to expose landrace chiles to a wider market. Since 2017, Duffy has assiduously tracked down and curated many of New Mexico’s rarest landrace chiles, including chimayós, to offer his customers. He understands that landrace chiles have a provenance, but argues that, from a historical perspective, that can be up for grabs.

“Remember, chiles did not originate here. They all can be traced back to South America,” he says, rationalizing that if grocery stores only stocked items from one particular source, there would be little left to buy. With proper care, he says, it is possible for gardeners in all growing regions to produce landrace chiles close in flavor to those grown in their native habitats.

NMSU Vegetable Specialist Stephanie Walker sees the issue from both sides of the garden fence.

“The whole thing about landrace chiles is that they’ve become adapted to the local environment after years and years of growing in that particular environment and saving seed,” says Walker. Growing these unique chiles in different soil, she notes, will eventually cause them to “drift from generation to generation from what they originally were.” But if forced to choose between their disappearance or preservation, albeit as some slightly modified version, she welcomes the latter. “Maybe a new type will emerge that works very well as the generations go,” she says. “That [will be] a great thing.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook