The Artist Who Imagined Zaire as a Miniature Utopia

In his multimedia sculptures, Bodys Isek Kingelez offered a fantastical vision for the freshly independent country.

When Zaire, now known as the Democratic Republic of Congo, gained independence from Belgium in 1960, a cohort of people who had grown up under the colonial regime set out to draw the future of the country.

Bodys Isek Kingelez was trying to figure out where he fit into it all. Born in the agricultural community of Kimbembele-Ihunga in 1948, he’d moved to the new capital city of Kinshasa a decade after independence. He attended university, where his coursework included industrial design. As he mulled over his career prospects, he wondered how to square them with the seismic social and political shifts that trailed decolonization.

In that place, at that moment, there was a “tremendous desire on the part of that country’s citizens to build a country, to build a nation, to build an identity for themselves,” said Sarah Suzuki, a curator at the Museum of Modern Art. Kingelez found this prospect thrilling, and he wanted in.

Civil service was intriguing. He considered a job as a magistrate, but knew that he was too reflexively judgmental to weigh evidence. Instead, he became a teacher. It was a way to shape the future of the country by helping to mold its youngest citizens, but Kingelez was “restless,” Suzuki said. He wanted to create something with his hands.

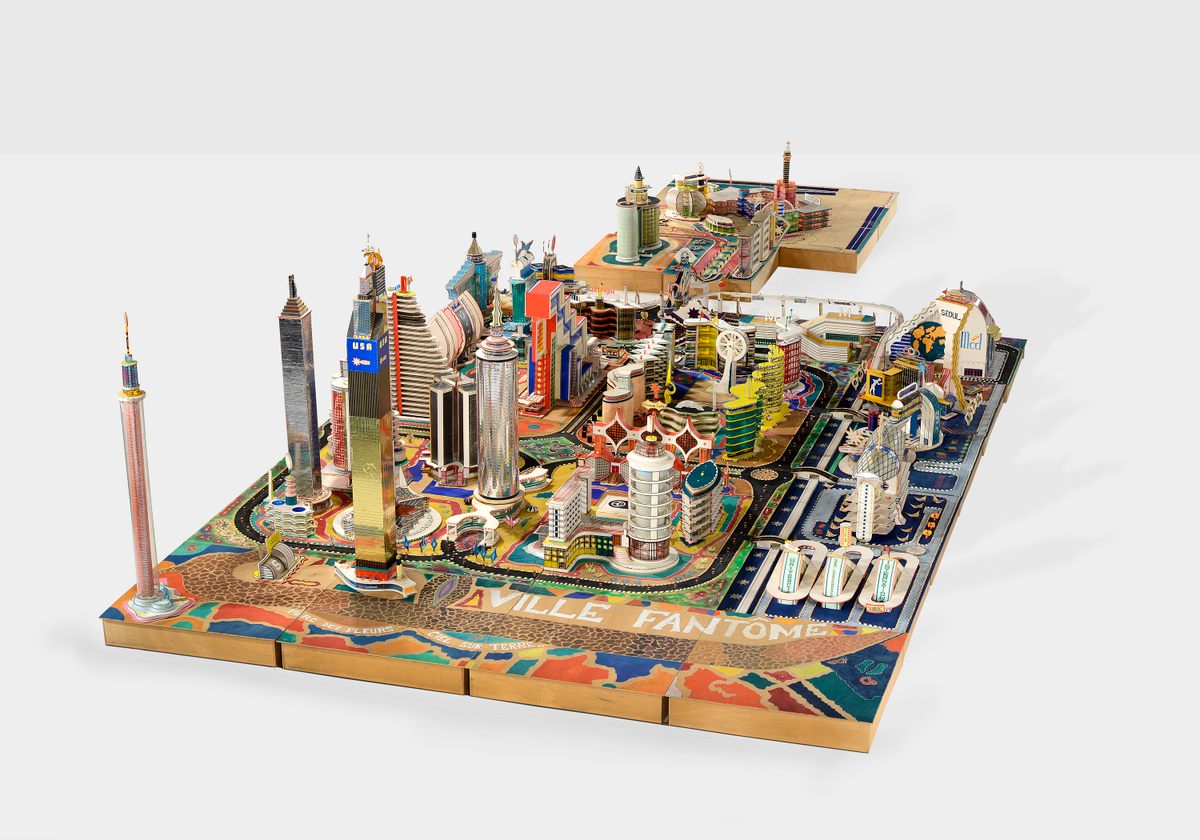

So, he did, and with a smattering of materials—paper, corrugated cardboard, twine, straws, wire, pushpins, plastic packaging, soda cans—he laid out a miniature sculptural blueprint for a city he’d like to see at human-scale.

He took his work to a museum, where the staff were so impressed that they hired him as a restorer. After a six-year stint caring for other people’s art, he devoted himself fully to making his own. Now, more than 30 of his architectural sculptures, which he dubbed “extreme maquettes,” are on view at MoMA in the solo retrospective Bodys Isek Kingelez: City Dreams.

Artists often envisage familiar utopias: worlds that meld the best parts of ours with other elements that feel out of reach. The show, curated by Suzuki, shows off Kingelez’s vision for little cities that he considered to be more perfect versions of the ones he’d seen.

In an era of rapid urban growth, he recast his hometown of Kimbembele-Ihunga as a metropolis outfitted with railroad stations, skyscrapers, and plenty of shopping.“What’s very present in Bodys’s work is an alternative,” Suzuki said. “A forward-looking, optimistic proposition for what the world could look like.”

In another instance, he dreamed of a town that had no use for doctors or police officers. Ville Fantôme, he said, was a “a peaceful city where everybody is free.” (And also free to slog through the drudgery of their daily lives—there’s ample parking, and a post office.)

The kinder, cleaner, more egalitarian neighborhoods of artists’ pages and canvases often remain in the realm of fantasy. Kingelez recognized that a brick-and-mortar utopia wouldn’t sprout up within his lifetime—many of the works incorporate dates that are still 1,000 years in the future—but he also thought he had hatched pretty good ideas. His version of Kinshasa is ringed by a kaleidoscope of blue butterflies, wings outstretched. He was convinced, Suzuki said, that “Kinshasa as planned by Bodys was much more beautiful.”

In the exhibition, a virtual reality tour leads visitors through the alleys between buildings, Suzuki explained, “as though you were a citizen on the street.” It’s not a guide to on-the-ground architecture, then or now. Instead, it’s one artist’s vision—colorful, glitzy, staggeringly exacting—for where to move the goal posts.

“Without a model, you are nowhere,” Kingelez once said. To be vital and sustainable, he suggested, an artist—or a populace—had to strive for something future-looking and envelope-pushing, however implausible. “A nation that can’t make models is a nation that doesn’t understand things,” he said. “A nation that doesn’t live.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook