Every Library Has a Story to Tell

Three new books for bibliophiles dig into the hidden human side of book collections.

A library is, at its most essential, a space that holds a collection of books. A dedicated room or building is not technically necessary. In his Book of Book Lists, recently released in the United States, author Alex Johnson offers examples of portable libraries—“sturdy wooden cases” of books and magazines that “were passed between lighthouses around the United States,” for instance. He includes the library Robert Falcon Scott took on board the Discovery in 1901, when the ship left for Antarctica, with a catalogue that specified which cabin a volume could be found in. Napoleon, he writes, had a traveling collection of French classics that was ported with him to war. It included five volumes of Voltaire’s plays and Montesquieu’s work on the Causes of the Greatness of the Romans and Their Decline.

But whatever form a library takes, someone had to have chosen the books in it, which reveal the secrets of heart and mind—their cares, their greeds, their enthusiasms, their obsessions.

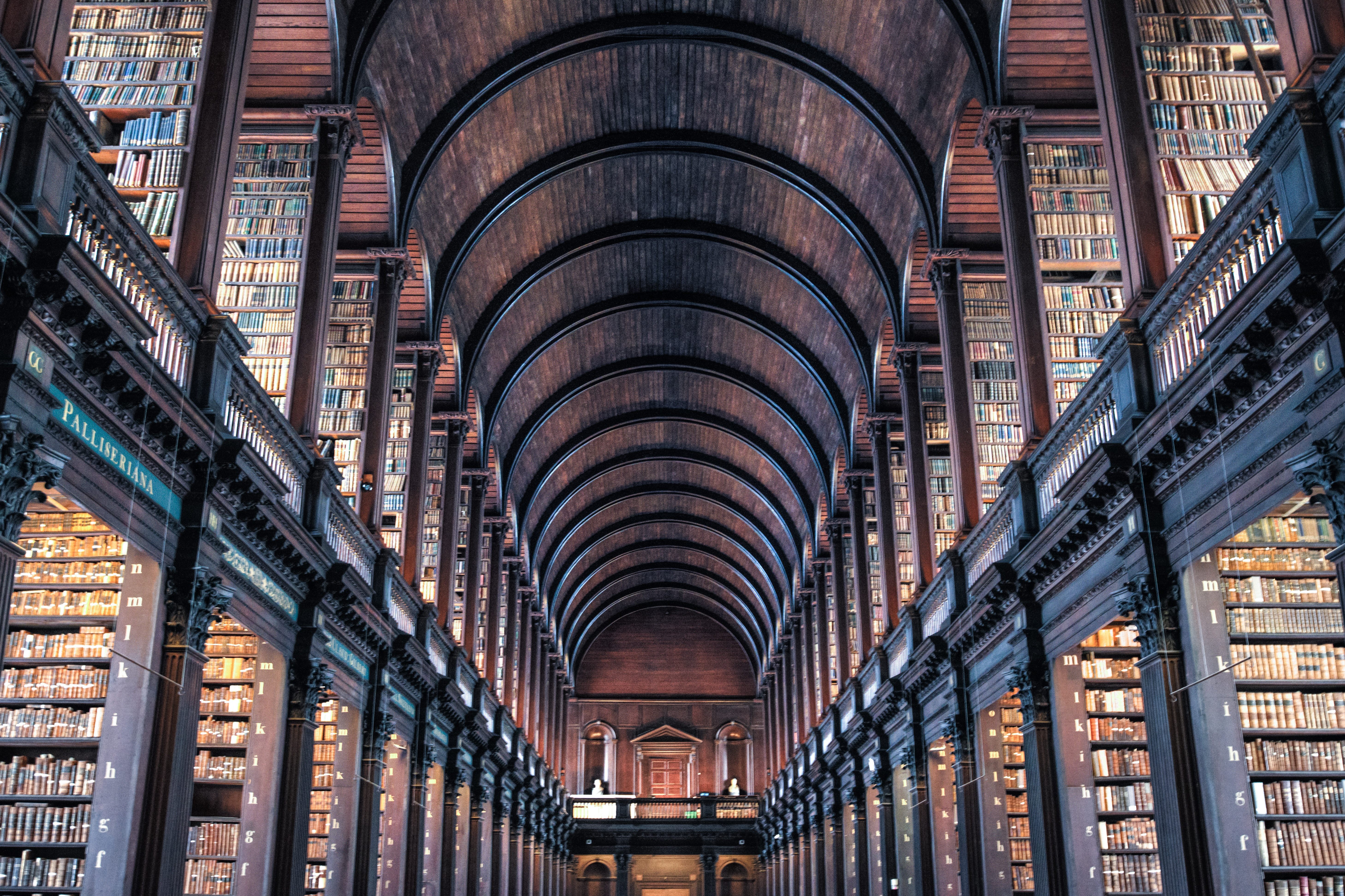

Libraries, writes Stuart Kells, a historian of the book trade, are “human places … full of stories.” Kells’s new book, The Library: A Catalogue of Wonders, offers a history that begins before the written word and follows the development of book collections through the digital age. At times, he takes a lofty view. “What exactly are libraries for?” he asks, after touching on the Library of Alexandria, medieval monasteries, erotic collections, the Vatican’s closed stacks, private collections, and university libraries, along with writers’ libraries, library fauna, and other curiosities. He takes a few stabs the answer. “Libraries are an attempt to impose order in a world of chaos,” he writes. “They are places of redemption.”

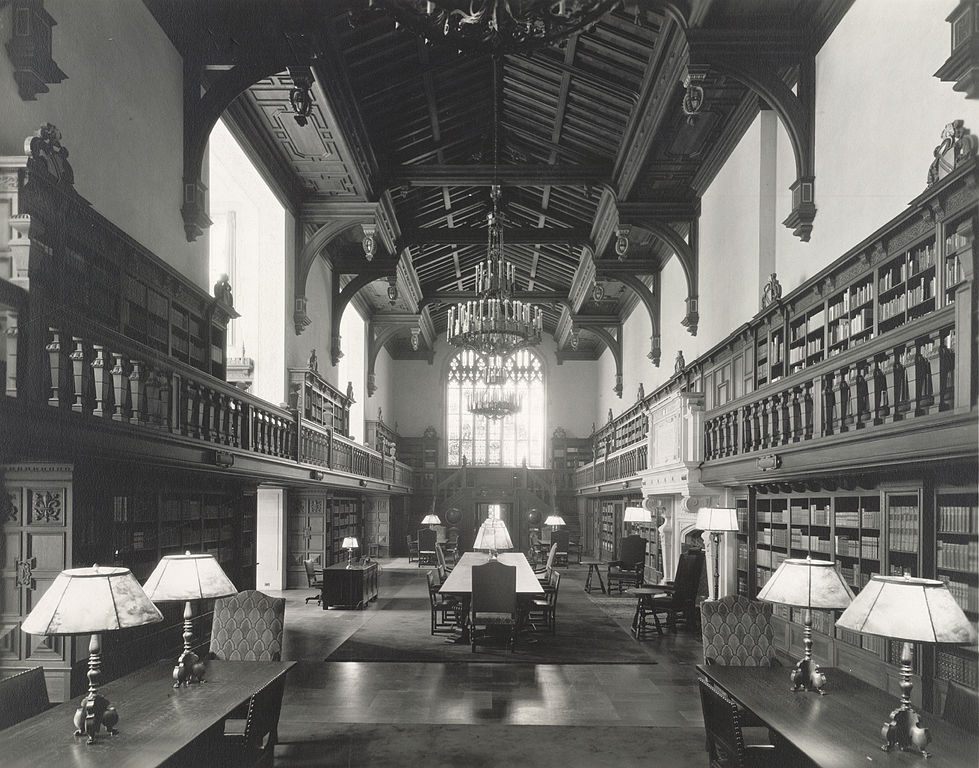

One of the institutions he features, the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C., provides a more concrete example of some of the many things a library can be. This one, at least, can be seen as a research center, a work of art in its own right, a mausoleum, or a bomb shelter. Starting in 1889, Henry Clay Folger, who made his fortune in the oil business, started buying up early Shakespeare folios until he had amassed one of the world’s most valuable collections of the bard’s work. But when scholars asked permission to study one of his prized possessions, he had to tell them it was impossible to know which bank vault he’d stashed it in.

Before his death, Folger built a proper library to house the collection, and architecture critics marveled. The ashes of Folger and his wife, Emily, are interred in the building, and underneath is a network of tunnels that, according to Kells, the staff planned to use for shelter during the Cold War. Today, it’s not only possible to study the folios Folger collected, but to compare them side by side. The library is a monument to both to Shakespeare and the man driven to collect his works.

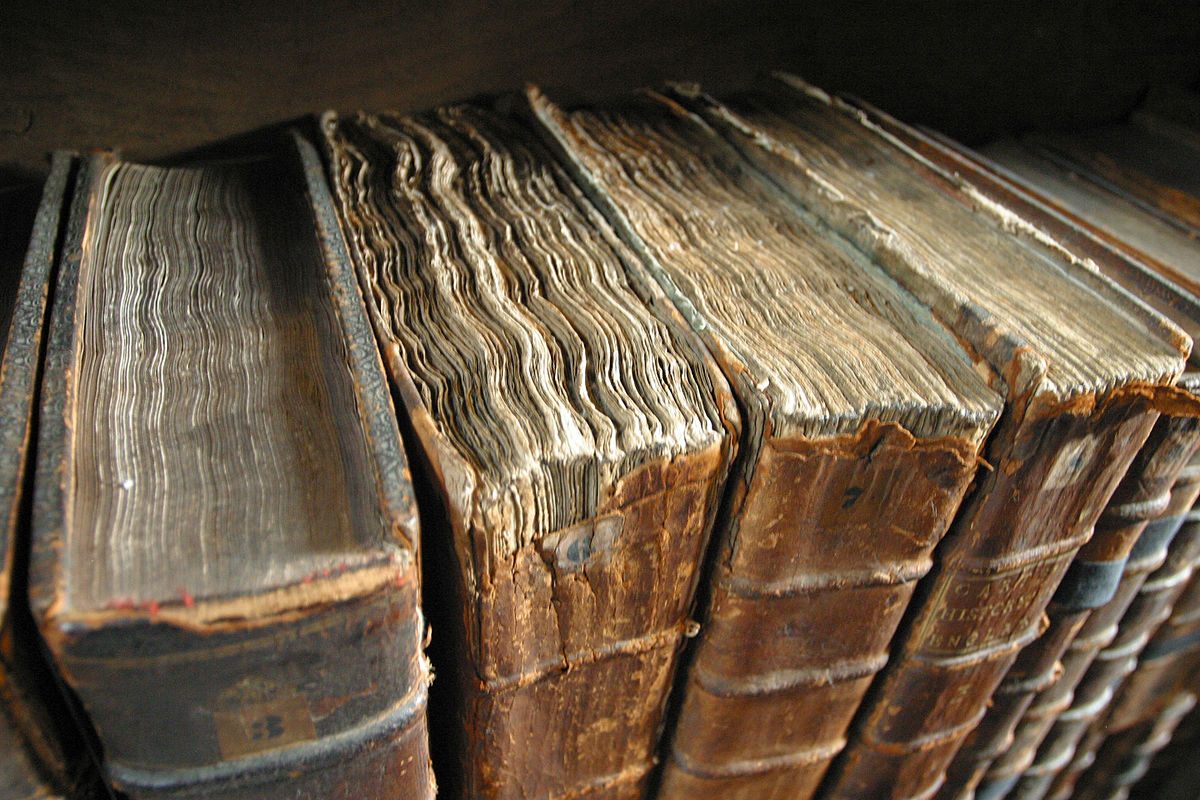

But if Kells wants to show that libraries are human places, he has also chosen stories that reveal their venal side. His librarians can be thieves, hoarders, or shameful caretakers. Even when they love books, they can’t be trusted with them. In its ideal form, a library protects books, celebrates them, and also makes them available to a wide group of readers. In this history, any single library rarely achieves all of these goals at once. Kells tells of libraries where valuable old manuscripts are left in piles on the floor, and others that exchange old treasures for new editions. Some libraries have ornate spaces that honor the idea of books but have very little on their shelves. Other libraries and book lovers have built amazing collections but zealously keep them from outsiders. What use is a library if no one is around to read its books?

In Packing My Library, Alberto Manguel faces down that question. At his home in France, Manguel kept 35,000 books in a tower library attached to a 15th-century barn and surrounded by a walled garden. Though he says he has only a few books that a serious bibliophile would find worthy, Manguel’s collection is as large as the best private libraries mentioned in Kells’s book and includes an illuminated Bible, a Spanish inquisitor’s manual, and rare first editions. For reasons never entirely explained, Manguel and his partner have to leave France, and the books in the library go into boxes. He laments its deconstruction.

Manguel’s is a personal history, and it is carefully curated. Like Kells, he offers digressions, because, he writes, when he was in the library he became “distracted by questions that are alien to my purpose.” That’s part of the charm of a library—it “orders the joyful chaos of the world”—and Manguel is a charming person to explore this chaos with. His world has an air of gentility; even as he insists his library isn’t so impressive, he mentions “the copy of Kipling’s Stalky & Co. that Borges had read in his adolescence in Switzerland and which he gave to me as a parting gift when I left for Europe in 1969.” Yes, he is talking about Jorge Luis Borges, whom he met as a young man. “I used to meet Borges after school, and walk him back to his flat, where I would read for him stories by Kipling, Henry James, Stevenson,” Manguel writes. He eventually took Borges’s old job as Director of the National Library in Buenos Aires.

The title of Manguel’s book comes from philosopher Walter Benjamin’s essay “Unpacking My Library,” which was written at a disorderly moment in his life. Benjamin and his wife had split up, and at close to 40 years old he was living alone for the first time. His books had been packed away for two years. As he unboxes them, he finds himself caught in “the spring tide of memories,” which reveals to him moments of his past. For Manguel, a library has a similar purpose. “I’ve often felt that my library explained who I was,” he writes.

In Benjamin’s view, a real library is always “somewhat impenetrable and at the same time uniquely itself,” as intriguing, loved, and yet unknowable as a close friend. Borges, in his famous story “The Library of Babel,” imagined a library that could hold every possible book, which the narrator calls, simply, “the universe.” The endless rooms of books drive the librarians wandering inside them to question the nature of knowledge and existence, and because the Library is infinite it is a place of possibilities. Though there is an order to it, it’s impossible for any one person to comprehend.

Similarly, any good library is too large for its owner to experience whole in a lifetime. Manguel’s book is about mortality. He is getting older, and his library may never be unpacked. If a collection is boxed away, it’s impossible for people to have relationships with the books, the act that endows them with meaning. But an imagined library has a life of its own. Manguel quotes his Latin teacher when he writes, “We must be grateful that we don’t know what the great books were that perished in Alexandria, because if we knew what they were we’d be inconsolable.” The memories of a library can be almost as powerful as the real thing. As Borges understood, imagining the true, unknowable depths of libraries’ secrets is the key to their attraction.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook