Dracula Lives! (in Philadelphia)

The Rosenbach museum is home to Bram Stoker’s original notes on vampires and a growing collection of undead literature.

A.W.S. Rosenbach was the best-known book collector and dealer of the late 19th and early 20th century, says Edward G. Pettit, the manager of public programs at the Rosenbach museum in Philadelphia. “He would pay the highest prices, and he would publicize it,” Pettit says. Rosenbach loved Sherlock Holmes and the works of Lewis Carroll—both of which are well represented in museum that was established in his will—but he probably wouldn’t have been into the pieces that are now among the most famous in the collection: more than 100 pages of Bram Stoker’s original notes on Dracula and an expanding collection of early vampire literature. “Dracula was definitely not considered literature in his day,” says Pettit, who hosted a popular online book club called “Sundays With Dracula,” which analyzed each chapter of the novel over the same period of time in which the book takes place, from the first week of May through the first week of November.

Atlas Obscura talked to the bibliophile about the rehabilitation of Dracula and our undying love of the blood-sucking undead.

How did the Rosenbach come to own Stoker’s notes?

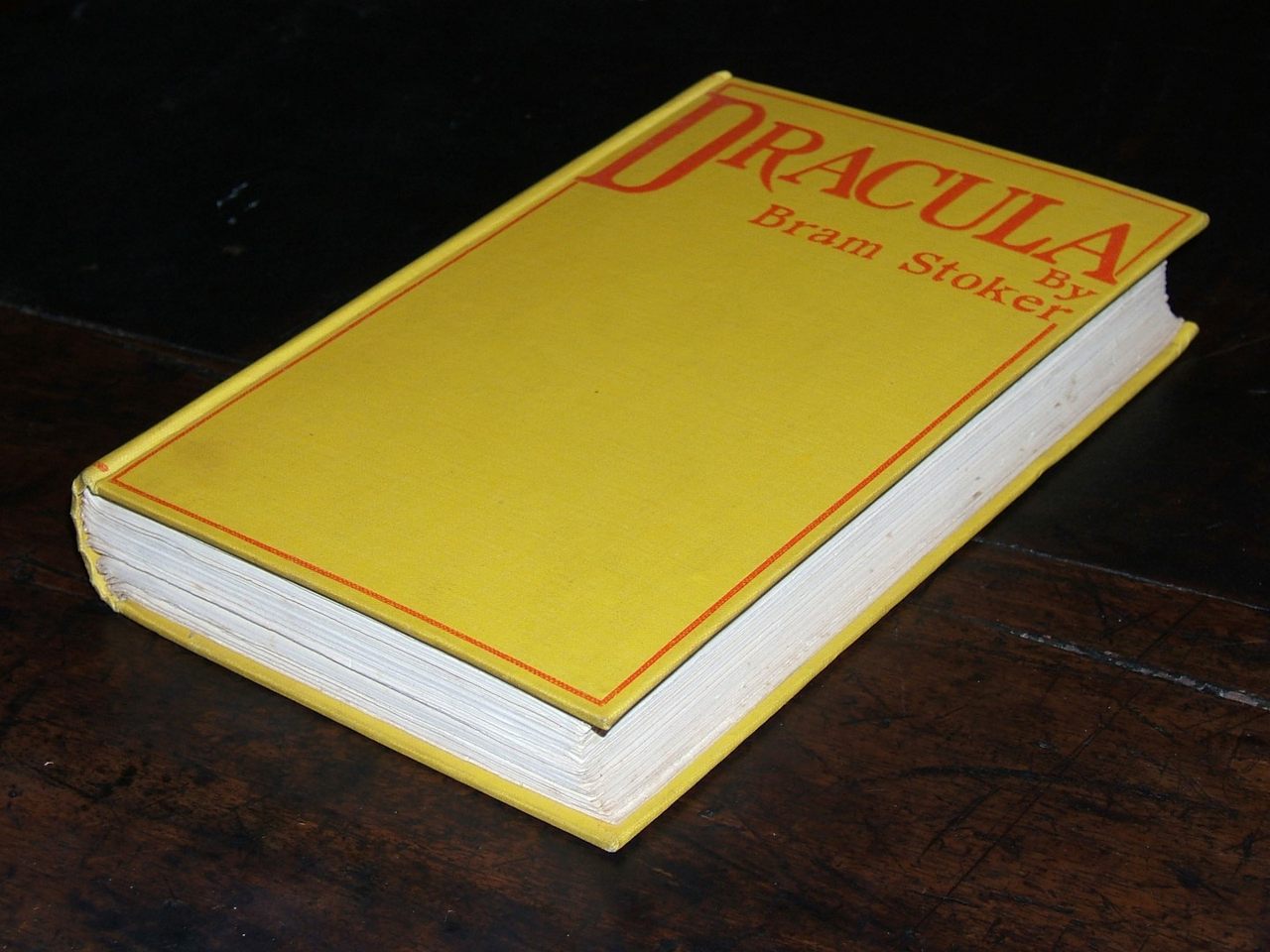

Rosenbach didn’t buy Bram Stoker’s notes for Dracula, which is where our vampire-related holdings began. It’s hard to say if he would have bought it, but it doesn’t seem likely because he never showed any interest in the gothic. The Rosenbach museum bought the notes in 1970, 20 years or so after he died, and we’re still collecting. We purchased several more vampire-related items in the last year, including a nice first edition with a dust jacket of Dracula printed in Irish in 1933.

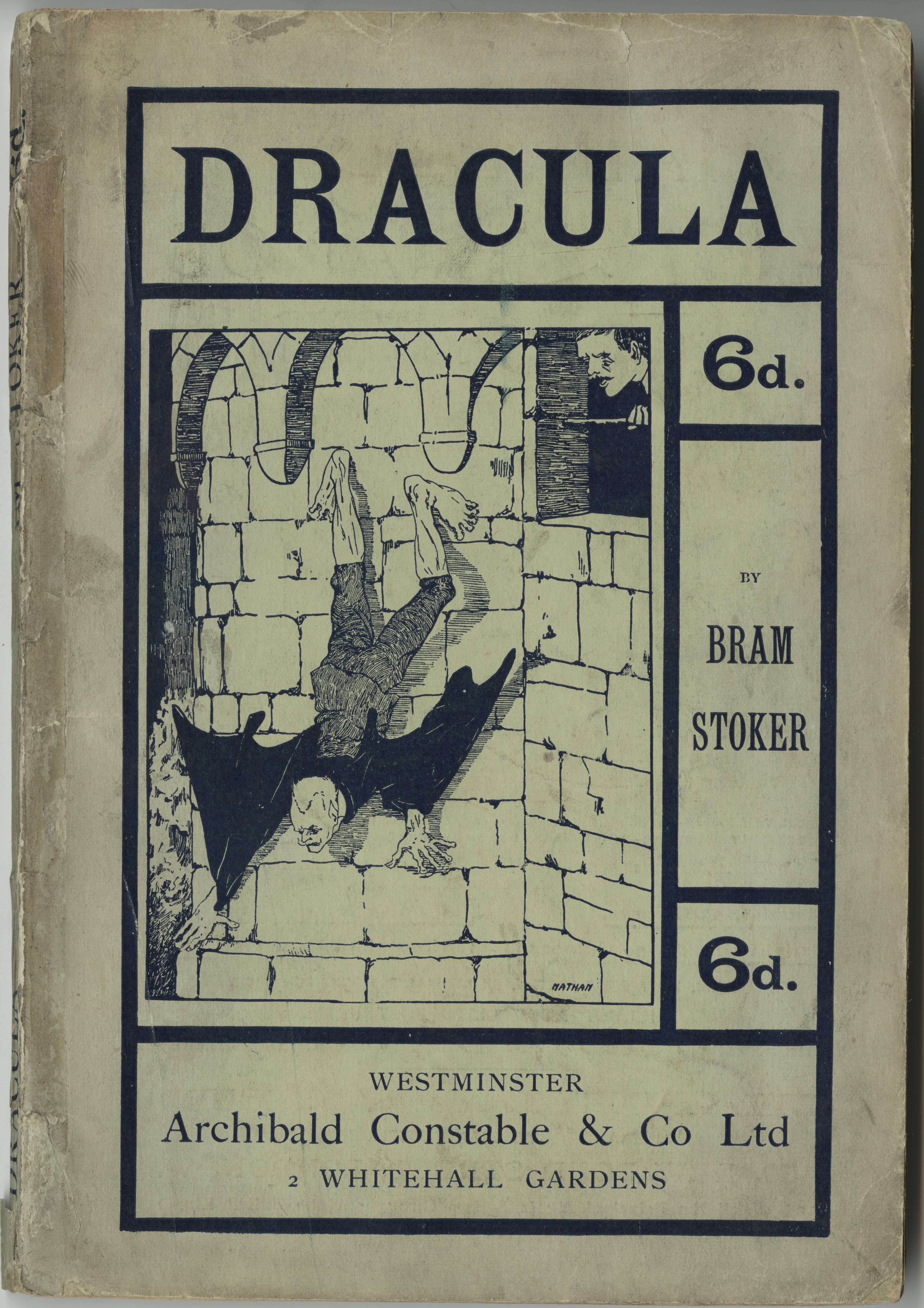

It was forward-thinking in 1970 to buy this, because Dracula was certainly not a studied novel. It certainly wasn’t taught. Genre literature in general was not considered part of the canon. Often people thought that if it was popular literature for the masses, that it is not serious literature. Dracula falls into that category. It wasn’t enormously popular when it was first published [in 1897] but it sold enough to stay in print, and then came the stage productions and film productions and suddenly Dracula was very influential across popular culture. Now you’d be hard pressed to find anyone in the world that doesn’t know that Dracula is a vampire.

What makes the notes valuable?

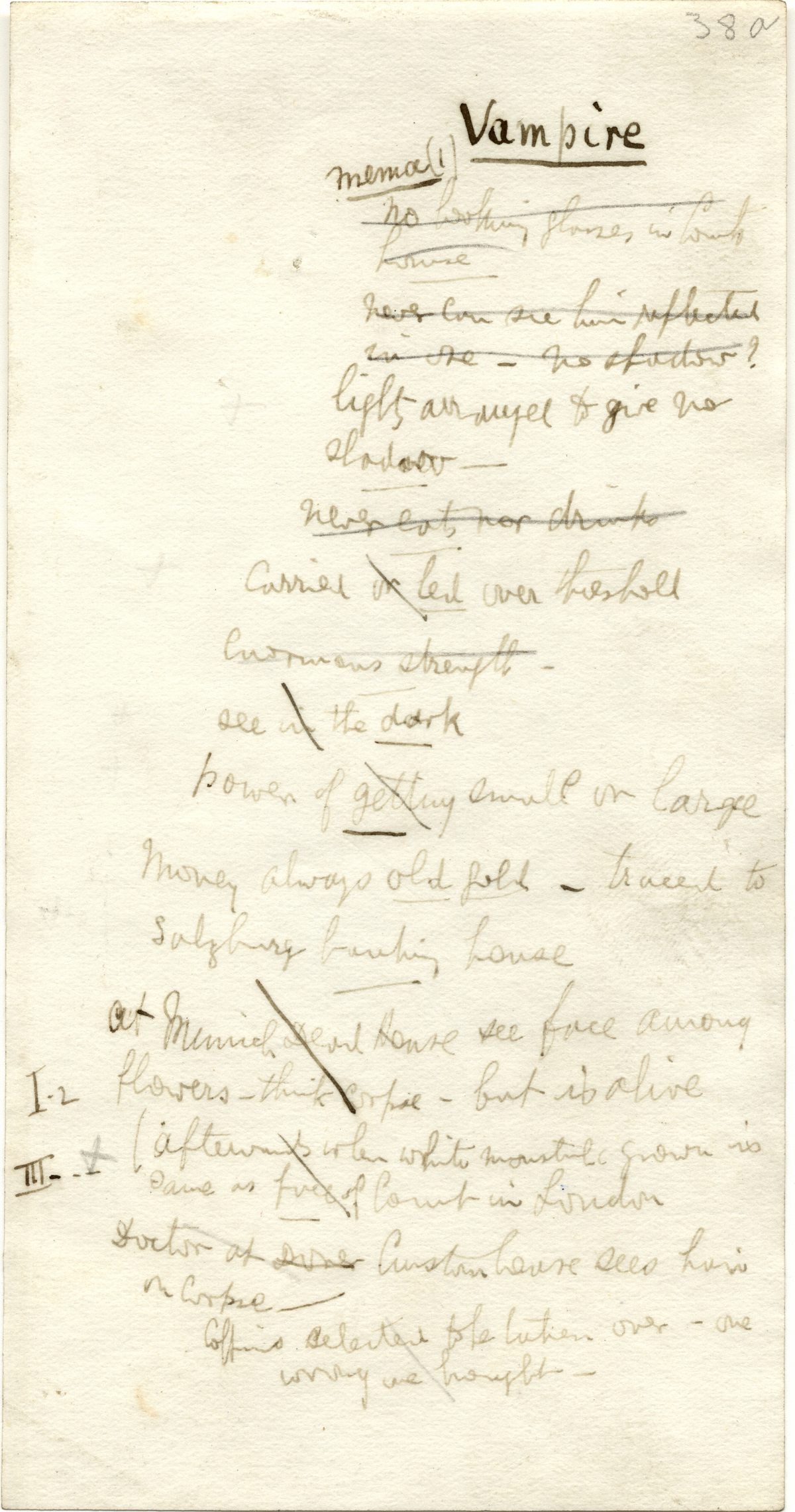

They are an unparalleled collection of notes from the 19th century about how someone put together a novel—in this case a novel that has come to be very influential in popular culture. They show the conception and development of the novel over the course of seven years, and they reveal how an author put together an imaginative work through various resources— scientific research, folkloric research, travel writing. He even goes into studying tide tables and weather patterns. It’s a unique item.

How did Dracula shape our idea of what a vampire is?

Stoker came up with the rules of vampirism as they are most widely known today: what a vampire is, how you become a vampire, what a vampire’s powers and weaknesses are. None of that was set in stone. All the vampire folklore and literature before Stoker is varied. Vampires have different kinds of powers and even how you kill them changes. Stoker puts together a list of characteristics for vampires, and there’s some things in the notes he ends up cutting out. One of them is “insensiblity to music.” Being a monster, you wouldn’t be able to understand this great art. One of the others is “couldn’t Kodak him”—as in the early Kodak cameras. You couldn’t photograph a vampire. Instead, it would turn out like an X-ray, which was a new technology at the time. It’s fascinating to read all those little details.

Why are we so obsessed with these suckers?

The interest in vampires has not gone away since people came up with this way of talking about a monster that is an undead creature that preys upon the living—and specifically, now, it is by drinking their blood, the thing that represents the life that runs through your body. That fascination is rooted in our anxiety over death. And vampires are tied up in the way we relate to each other and how we relate to each other in intimate ways. The vampire bite is a sensual thing.

Our vampire holdings attract attention from a lot more than serious academics. There are people who are fans, who love reading vampire works, and they can come to the Rosenbach and look at Bram Stoker’s notes. It’s really nice to bring all those people together under this shared interest, especially in an age when everyone is being separated by different ideas and concepts and groups. That’s so corny, I guess. It’s just a vampire story, but people are really attached to it.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook