The Long, Hidden History of the Viking Obsession With Werewolves

A symbol both of chaos and order, the wolf came to represent many things for the Vikings.

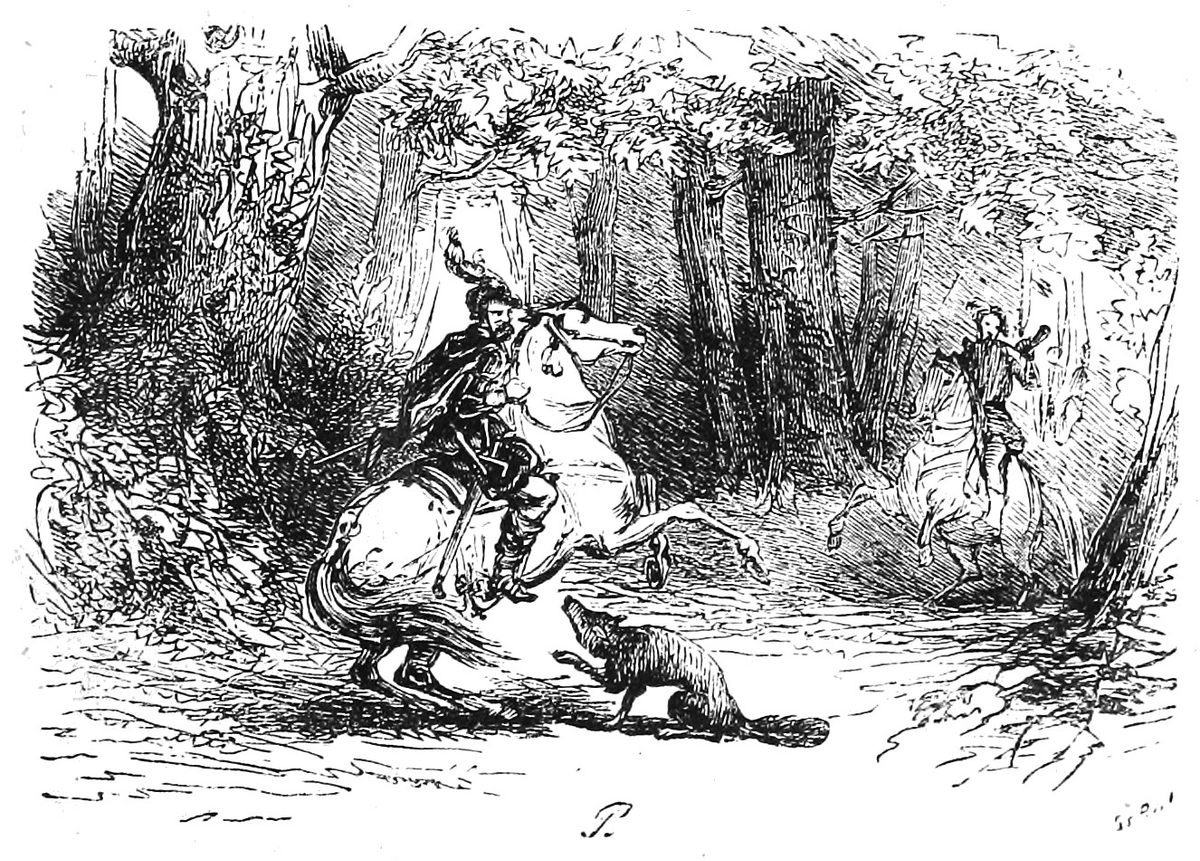

After a hard day’s work of thieving, Sigmundr and his son Sinfjötli happened upon a house. It looked empty, so they slipped inside to find two wealthy men fast asleep. Hanging above them were two luxurious wolfskins. The father and son helped themselves—they were thieves after all. But when they put the pelts on, they started to walk on all fours and grow long, fang-like teeth. They howled at the night sky and bared their teeth. Out in the forest, they confronted several bands of men and left none standing—more than 13 victims between them. With no one left to stalk, Sigmundr attacked Sinfjötli, digging his long teeth into his son’s neck. When he realized what he’d done, he used a magical herb to restore Sinfjötli’s health. Eleven days after their transformation, father and son finally returned to their human form and burned the nefarious pelts.

The story of Sigmundr and Sinfjötli is one of the Viking world’s oldest and most popular tales, passed down orally for centuries before being written down in the Vǫlsunga Saga around 1270. It turns out the Vikings were a bit obsessed with wolves and the people who become them. There are upwards of 50 different werewolf stories Vikings would tell around roaring fires to help pass long, dark Scandinavian winters. Wolves, such as the world-ending Fenrir, are woven into their mythology. Viking warrior bands would growl and howl and bite in battle, and sometimes even attack their compatriots in their frenzy. It’s something victims of Viking raids also saw in the Norsemen who descended on them from the seas; they referred to them as “sea-wolves” and “ware-wolves” in medieval histories. Even after the raids stopped, popular stories linked Viking descendants to werewolves (if slightly nicer ones). The Viking obsession with wolves extends to the artifacts they left behind, such as the elaborately carved animal-head posts found in the Oseberg burial, part of the recently announced new Museum of the Viking Age in Oslo.

Viking werewolf stories, like Sigmundr and Sinfjötli’s, reflect the complexity of the wolf as a symbol in Viking society. Vikings both admired wolves’ strength and, as a largely agricultural society, feared it. “[Wolves] prowl on the edges. They’re destroyers, kind of night-creatures, and they are strongest in some ways where we are weakest,” says historian Lars Brownworth, author of The Sea Wolves: A History of the Vikings. And yet, “Vikings, especially particular tribes, embraced the connection” to wolves, says Dutch historical anthropologist Willem de Blécourt.

In one sense, wolves exist “outside of society,” says Brownworth, noting that the word for “exile” in Old Norse, vargr, is the same word used for “wolf.” Being exiled in Viking society meant living like a wolf in the forest, an enemy to mankind. As Stefan Brink writes in The Viking World, being exiled was “the worst punishment” for Vikings. In a society in which family and social ties were everything, it was akin to a social death—and could often lead to literal death, too, since exiles could be killed with impunity. In his Danish History, late-12th-century historian Saxo Grammaticus wrote about another wolf-related punishment. Any Viking who kills a close family member would be strung up by the heels next to a live wolf—“he having acted as a wolf which will slay its fellows.”

And yet wolves, and packs specifically, are also symbolic of powerful social order. “Viking society functioned very much like a wolf society, with these alpha males who would occasionally work together,” says Brownworth. The sagas are full of blood feuds and quarrels between various Viking chieftains, but occasionally those chieftains could work together, consolidate power, and, eventually, create the framework for modern Scandinavian nations.

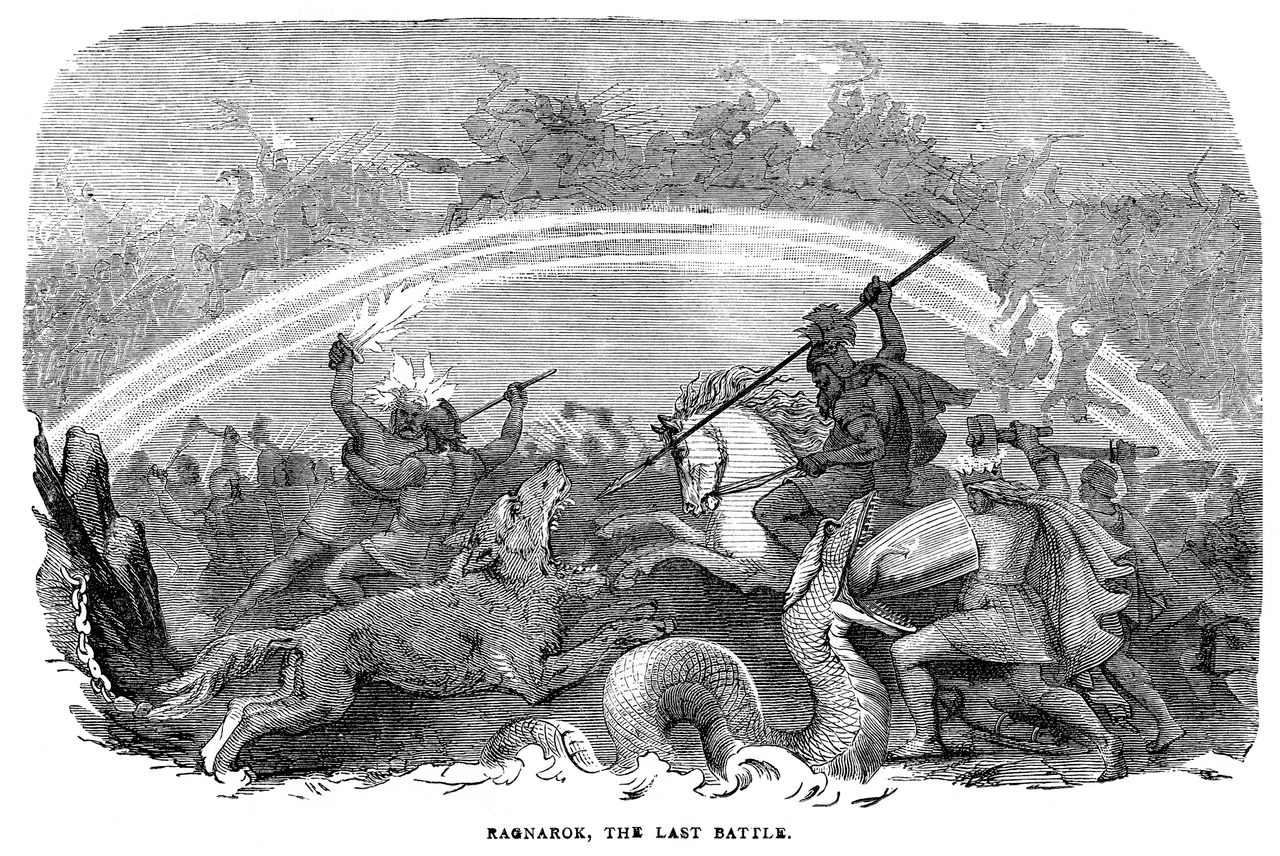

The duality of the wolf is also embedded in Norse mythology. The gods bound the anthropomorphic wolf Fenrir, son of the trickster god Loki and the giantess Angerboda, in magical chains, knowing that on Ragnarok, the Viking doomsday, “the fetters will burst, and the wolf run free,” as the 10th-century poetic Völuspá prophesizes. On Ragnarok, Fenrir will devour the sun and kill Odin, king of the gods. And yet, wolves (along with ravens) are dedicated to Odin. In the poem Grímnismál, two wolves, Geri and Freki, are said to accompany the trickster god everywhere he goes. “Freki” and “Fenrir” are even sometimes used interchangeably in Old Norse texts. In his book Norse Mythology: A Guide to Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs, folklorist John Lindow notes the irony of Odin feeding one Freki and becoming food for another Freki (or Fenrir).

The Odin-worshipping warrior bands known as úlfhéðnar would, according to Viking sagas, bite their shields, make blood-curdling howls, fight with their fingernails, and seem to experience no pain in battle. Instead of traditional armor, úlfhéðnar are said to have worn wolf skins. There might have been some sort of shamanistic or magical ritual that úlfhéðnar would undergo before battle to “connect spiritually with the spirit of the wild animal,” says Old Norse literature expert Aðalheiður Guðmundsdóttir, from the University of Iceland. For young Viking warriors, this might’ve been a necessary delusion. “It’s much easier to go into war imagining yourself to be a wild animal,” she says, “than the teenager that you are.”

Like their wolf counterparts, the úlfhéðnar were both feared and respected. Brownworth references Harald Hardrada’s saga, in which the fearsome warriors start “attacking his own men because they’re completely senseless.” And yet the battle-frenzied úlfhéðnar are also considered elite warriors. Norway’s first king, Harald I Fairhair, kept a band of them as his bodyguard. The eighth-century poet Hornclofe’s “Raven Song” lauds that unit:

Wolf-coats they call them that in battle

Bellow into bloody shields.

They wear wolves’ hides when they come into the fight,

And clash their weapons together.

After all, the úlfhéðnar were followers of Odin, the god both of madness and wisdom, says Brownworth, and, like Odin, they are complex, even contradictory figures.

The Viking werewolf stories recorded in the sagas are, in many ways, a literary legacy of the úlfhéðnar. All the earliest werewolf stories are connected to war, says Guðmundsdóttir. In the case of Sigmundr and Sinfjötli, Sigmundr takes his son into the woods, since to become “a fully trained warrior Sinfjötli must come to know his animal nature, the wild animal within him,” writes Guðmundsdóttir in an article entitled The Werewolf in Medieval Icelandic Literature. But, as Brownworth notes, that’s not entirely a good thing. When they become wolves, “they start off like, ‘Oh, this is neat.’ But they quickly lose themselves and go on this killing spree.” Even after Sigmundr and Sinfjötli return to their human bodies, their family’s association with wolves continues. Sinfjötli is called ylfingr, a “wolfling.” Sigurðr, another son of Sigmundr, when asked his name, says, “I am called the noble beast,” a reference to a wolf, writes Guðmundsdóttir. Of 46 Icelandic sagas, 14 of them have werewolves prowling about, and there are even more stalking the Norwegian sagas.

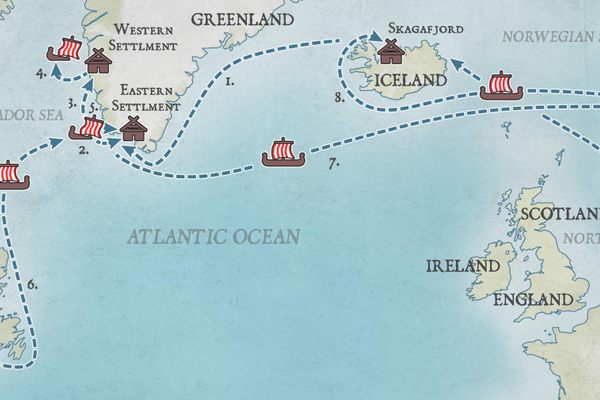

For the Europeans on the receiving end of Viking raids, equating their attackers with wolves and werewolves didn’t come with the same complexity. The metaphor only served to paint the Vikings as terrible, almost inhuman warriors. In the 11th century, Norman monk William of Jumieges compared Vikings to “agile wolves set out to rip apart the Lord’s sheep.” In an anonymous Old English poem recounting the 991 Battle of Maldon, the Vikings were described as “the wolves of slaughter.” When recounting the raid at Lindisfarne, the English chronicler Simeon of Durham writes that the Vikings, “like fearful wolves, robbed, tore and slaughtered not only beasts of burden, sheep, and oxen, but even priests and deacons, and companies of monks and nuns.” Wolves were brutal; Vikings were brutal. For Europeans, the metaphor didn’t carry much meaning beyond that—at least for several centuries.

Many use 1066, the year of William the Conqueror’s conquest of England, as the end of the Viking Age. But that history forgets that William was Duke of Normandy and a descendant of the Vikings that settled there. The Vikings “had this incredible adaptability,” says Brownworth. It’s the Vikings and their descendants that build “the two greatest medieval states in Europe,” England and Sicily.

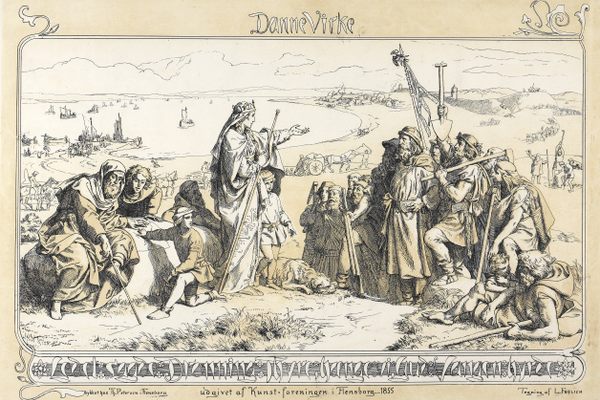

Not everyone was quick to forget William’s ancestry, though. In the 12th century, the French poet Marie de France wrote Bisclavret, the “Werewolf.” The story was widely circulated and versions of it made it all the way to Iceland. The story follows a baron who transforms into a wolf three days of every week and is only able to return to his human form when he puts his clothes back on. But when his wife steals his clothes, he becomes fixed in his wolf form until the king, learning the truth, returns the baron’s clothes and reinstates his lands and title. Marie de France wrote the story a century after William’s conquest, likely for the court he established there. Blécourt theorizes the story was a way for Marie de France to point to the Normans and say, “I know you’re still wolves.” I know you’re still the descendants of Vikings. Guðmundsdóttir says Bisclavret, along with other, later werewolf stories, all contain versions of the “romantic werewolf.” Found in courtly, chivalric tales across Europe, these later werewolves are “sympathetic,” unlike the frenzied, martial wolves of earlier sagas. As the Vikings integrate more and more into Christian European society, so too does their werewolf, shapeshifting from a beast of war to a feudal baron.

It’s difficult today to fully understand the complexity of the Viking werewolf. The few wolf artifacts we do have often offer more questions than answers. Some scholars guess that one of the elaborately carved animal heads in Oslo’s new Museum of the Viking Age might be one of Odin’s wolves, but maybe not. Runestones such as the 11th-century Ledberg Stone definitely have wolves prowling about, but what exactly those wolves are doing isn’t clear. Are they devouring Odin? Do they commemorate a warrior killed in battle? But what the artifacts, sagas, and histories do tell us is the importance of the wolf and werewolf as a symbol for the Vikings. “I don’t know of any other society that had that same view of wolves,” says Brownworth, “where the wolf played such a large role and also kind of an ambiguous role.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook