New Discovery Uncovers a Forgotten Viking Queen More Celebrated Than Kings

Her legacy is being restored, thanks to runestone forensics.

When you think of Vikings, your mind may imagine the muscular Norse Gods: Thor, Odin, or Loki. Or perhaps you might picture fierce-looking bearded men aboard slender, symmetrical boats rowing oars in unison, commanded by feared war heroes like Ragnar Lothbrok.

Yet a recent investigation has found that, during the Viking Age, one of the most celebrated leaders was actually a woman. A recent study has found that Queen Thyra is honored on runestones far more than any male counterpart.

Runestones are ancient monuments that are inscribed with runic writings, most commonly found in Scandinavia and made during the Viking Age (late 8th century to early 11th century). They contained information on significant events: the erection of infrastructure, the details of battles, or to commemorate the dead. To be carved into this rock, the way Thyra was on so many across Denmark, would have been considered a big deal.

So why are we only just finding this out now?

Historians have been formally studying Vikings since the early 19th century, but they largely sidelined Viking women’s accomplishments. Jóhanna Katrín Friðriksdóttir, author of Valkyrie: The Women of the Viking World, explains that “having powerful women doesn’t fit into a world view which is very male, heterosexual, based on certain values and attributes.” She says many history books had narrowed their focus on “kings and warriors and ships and weapons.”

When Katrín Friðriksdóttir first studied the medieval manuscripts that contained the sagas of Viking history, she was amazed to see so many “rich, fascinating, and nuanced narratives” on Viking women who leveraged their power.

But Queen Thyra, who lived in Denmark in the 10th century, had previously been considered a side plot to other male figures. She married King Gorm, and a study from 1913 referred to her as “the wife of Gorm the Old,” even though Gorm was only mentioned on one runestone and Thyra has been found on four.

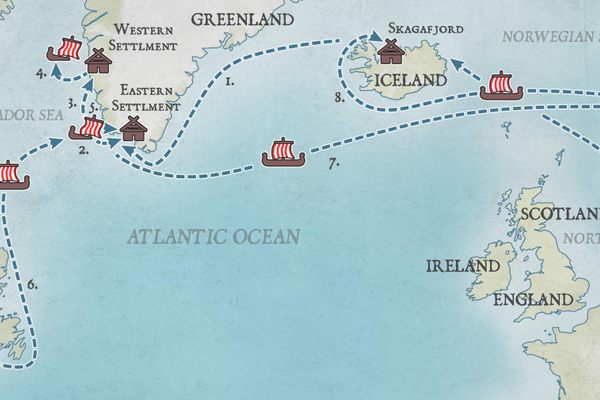

That’s even more than Thyra’s more well-known son, Harald “Bluetooth” Gormsson. Harald is considered a notable leader who unified Denmark with present-day Norway and Sweden (and yes, our wireless Bluetooth networks are named after his legacy of connection). But new evidence is showing that Thyra may have been more involved in this expansion of Danish territory. The study says, “The combination of the present analyses and the geographical distribution of the runestones indicates that Thyra was one of the key figures—or even the key figure—for the assembling of the Danish realm, in which she herself may have played an active part.”

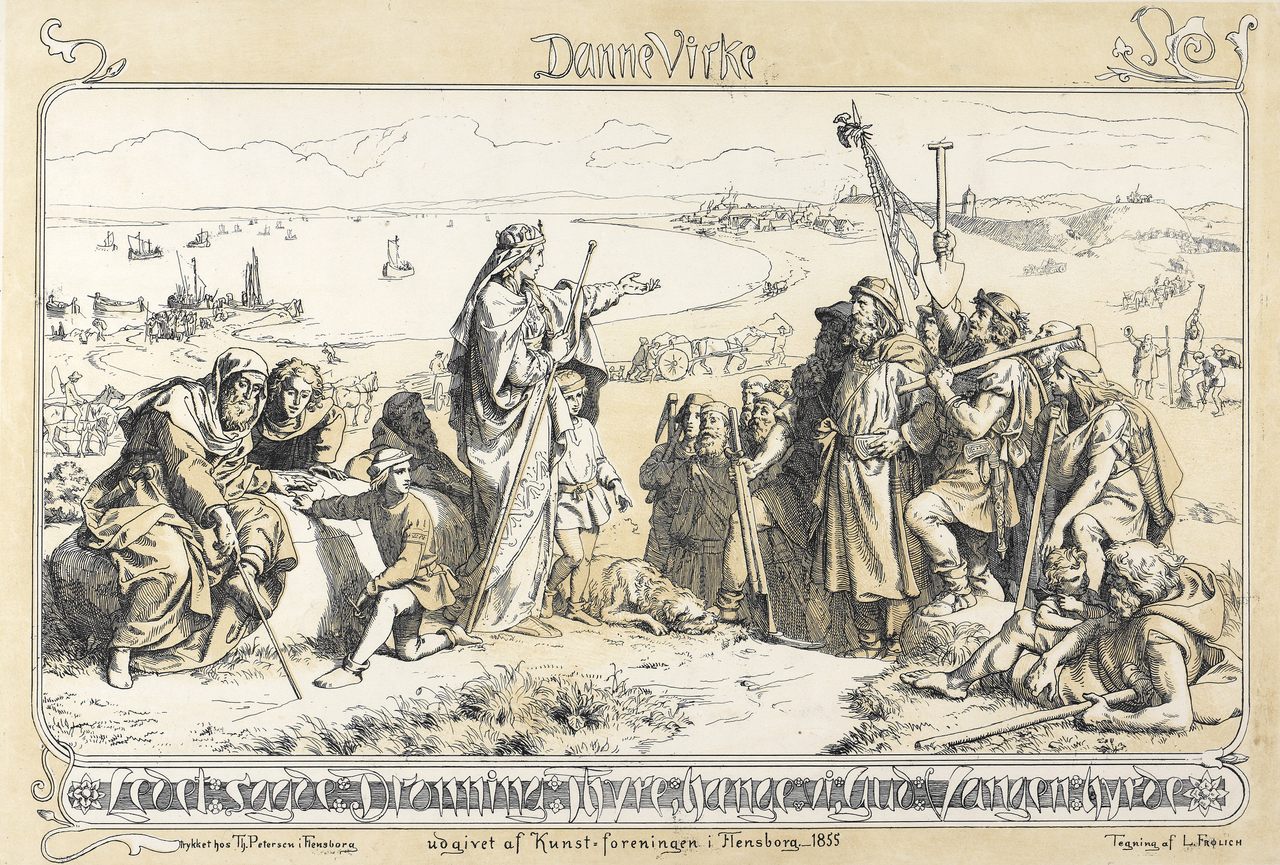

In addition, Sven Aggesen and Saxo Grammaticus were historians from the 12th century who described Gorm as a weak and lazy person, but credited Thrya with building the Danevirke fortifications in the south of Denmark, which held off foreign invasions.

Little else has been known about Thyra, since much of her history was passed down orally. However, Thyra’s presence on four different runestones has only recently been linked.

“There are two groups of stones with the name Thyra, and we have connected them,” says Kitzler Åhfeldt, an archaeologist and senior researcher at the Swedish National Heritage Board. Two of the runestones are located in the town of Jelling (which was once the royal seat of Denmark), and two are located in the nearby Danish towns of Bække and Læborg, but historians previously disagreed on whether they were all honoring the same Queen.

So Kitzler Åhfeldt decided to analyze the Jelling stones using cutting-edge technology. Kitzler Åhfeldt specializes in runic research. Her work has pioneered the utilization of 3D-scanning to analyze the ancient stones to ascertain their carvers. She searches for identifiers in the carvings in a way that’s comparable to modern-day forensic handwriting examinations.

“We need to look at the cross section of the groove and what happens in the cutting direction. We could record these variables by studying 3D models at a micro topographical level,” she explains.

After analyzing all four stones in this way, Kitzler Åhfeldt and her team were able to confirm that all of the runestones mentioning Thyra were carved by the same person, a rune-carver known as Ravnunge-Tue. On one of these stones, he even describes her as dróttning, meaning “lady” or “queen,” and the other Jelling stones he carved link her to Gorm and Harald, confirming her as the same queen. The study explains, “these honors point towards a powerful woman who held status, land and authority in her own right.”

The linking of the four runestones demonstrates her wide-spread impact. The fact that Thyra was mentioned on more stones than Gorm or Harald, “implies that she was the important figure here in this area,” Kitzler Åhfeldt continues.

More and more has been coming out about the power of Viking women, but this most recent study is a particularly crowning achievement. As Katrín Friðriksdóttir concludes, “every new piece of evidence adds strength to this picture of women as being powerful and able to be rulers.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook