In 19th-Century Britain, The Hottest Status Symbol Was a Painting of Your Cow

The livestock looked surprisingly geometric.

In 1802, London was home to a very special bull. It arrived in a specially designed carriage, after a tour of England and Scotland. At every stop, the ox drew crowds that came to stare at its massive size. Weighing nearly three thousand pounds, the existence of such a fat cow was a wonder.

The Durham ox was immortalized in a painting, and print reproductions sold by the thousands. But the ox was part of a much larger trend. Wealthy British landowners were breeding animals larger and fatter than ever before. Proud of their achievements and eager for recognition, they commissioned paintings of themselves and their livestock. And the public couldn’t get enough of them.

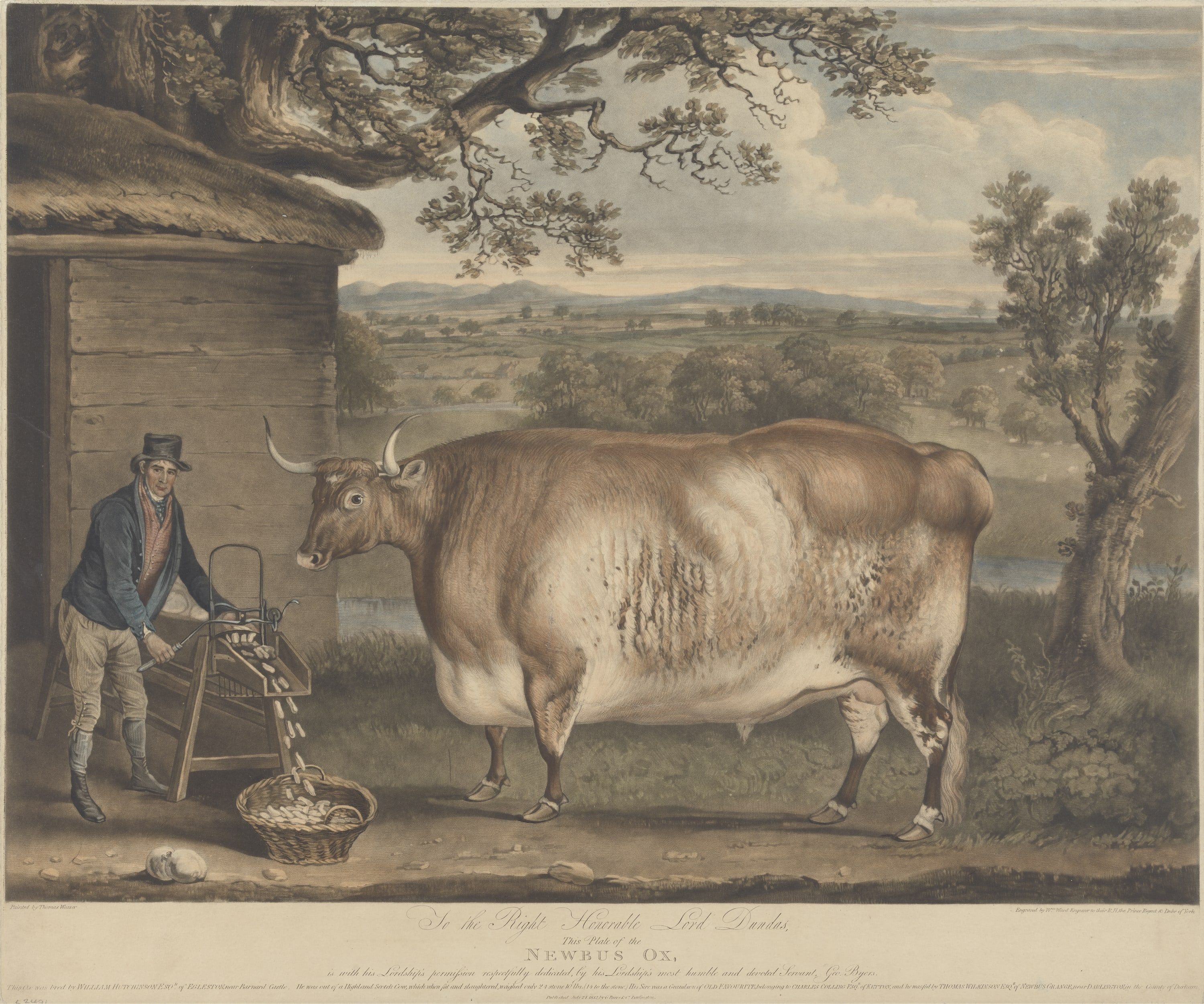

The early 1800s was the peak of livestock painting. Often the subject was racehorses, painted in slender lines denoting their speed and grace. But for farm animals, corpulence was key. In the paintings, the cow, sheep, and pigs are massive, yet oddly supported by only four spindly legs. Sometimes, their owner is painted in as well, proudly looking over their creation. Other times the animal stands alone, seemingly ready to eat a nearby village. The simple style is often referred to as rustic or “naive” art, even though the subjects were animals belonging to a wealthy elite. The resulting images were part advertisement and part spectacle.

Fat cows, massive pigs, and obese sheep were prized as proof of their owners’ success in breeding for size and weight. Gentleman farmers used selective breeding to create quick-growing, heavy livestock. Along with breeding, new farming and feeding practices also produced larger animals. Rich farmers participated in agricultural competitions and read new research. They were called “improvers,” since they tried to improve on existing animal breeds. Methods such as feeding cows oil cakes and turnips for a final fattening up before slaughter became widespread. Even Queen Victoria’s consort Prince Albert became an improver, showing off his prize pigs and cattle.

If an animal was especially large, its owner would use both exhibitions and art as self-promotion. This created a class of animal celebrities, such as the Durham ox, whose image was even used as a pattern for dinner plates. Exceptional animals could be sold for top dollar. But usually, only elite amateur breeders had the time and wealth to develop prize animals. Many noblemen and gentlemen owned large agricultural estates, and breeding was considered a high-class pastime. According to historian Harriet Ritvo, regular farmers were frequently warned in agricultural publications that trying to compete with the nobility’s tricked-out cows was expensive.

Ritvo also notes that gentry farmers used patriotism to justify the competitions and self-promotion. If elites could breed and feed larger, fattier cows, then poorer farmers could eventually own them. With more meat to sell, rural communities would be more financially stable. The national security of the country would benefit, or so went the argument. Britain’s population was quickly growing, and due to the prospect of frequent wars, having a secure food supply of fat animals was imperative. “Improvement” progressed quickly. The average weight of British cows increased by a third from 1710 to 1795.

Commissioned paintings and commercial prints often came with information like the animal’s measurements and the owner’s breeding efforts. According to animal studies professor Ron Broglio, the portraits were often exaggerated to emphasize the idealized animal shape, which usually consisted of “[providing] a bit more fat in crucial areas.” For pigs, the ideal was an American football shape. Cows were rectangular, and sheep tended towards oblong.

Beyond making wealthy farmers famous, animal paintings and prints had a practical purpose. Breeders across the country could use a specific animal’s image as a model for their own herd, since livestock that fit beauty ideals were worth much more.

Even today, the prize animals of yesteryear are compelling, but in a different way. Prints showing huge animals still hang in many a rustic-themed bar or inn, evoking a rural past. Many British pubs are even named after much-publicized cows such as “The Craven Heifer” and “The Durham Ox.” But these days, the livestock paintings aren’t a sign of prosperity or patriotism. Like dancing a minuet or competitive walking, they can seem so strange that they’re hilarious. In late 2016, a pig painting by an unknown 19th-century livestock artist even became a meme.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook