Resurrecting the Forgotten Bike Highways of 1930s Britain

The United Kingdom built hundreds of miles of protected bike lanes—and promptly forgot about them.

In the 1930s, Britain’s Ministry of Transport built an extensive network of bike highways around the country—at least 280 miles of paved, protected infrastructure dedicated to cyclists alone. For decades, it was entirely forgotten—overgrown and overlooked—so much so that no one seems to remember that these lanes had existed at all.

“There’s all this infrastructure, it’s been there for 80 years, and nobody knows what it was,” says Carlton Reid, author of the forthcoming book Bike Boom. Reid, who’s been a cycling journalist and historian for 30 years, rediscovered the network while researching his book. Now he’s teaming up with an urban planner to reveal the full extent of Britain’s historic cycleways.

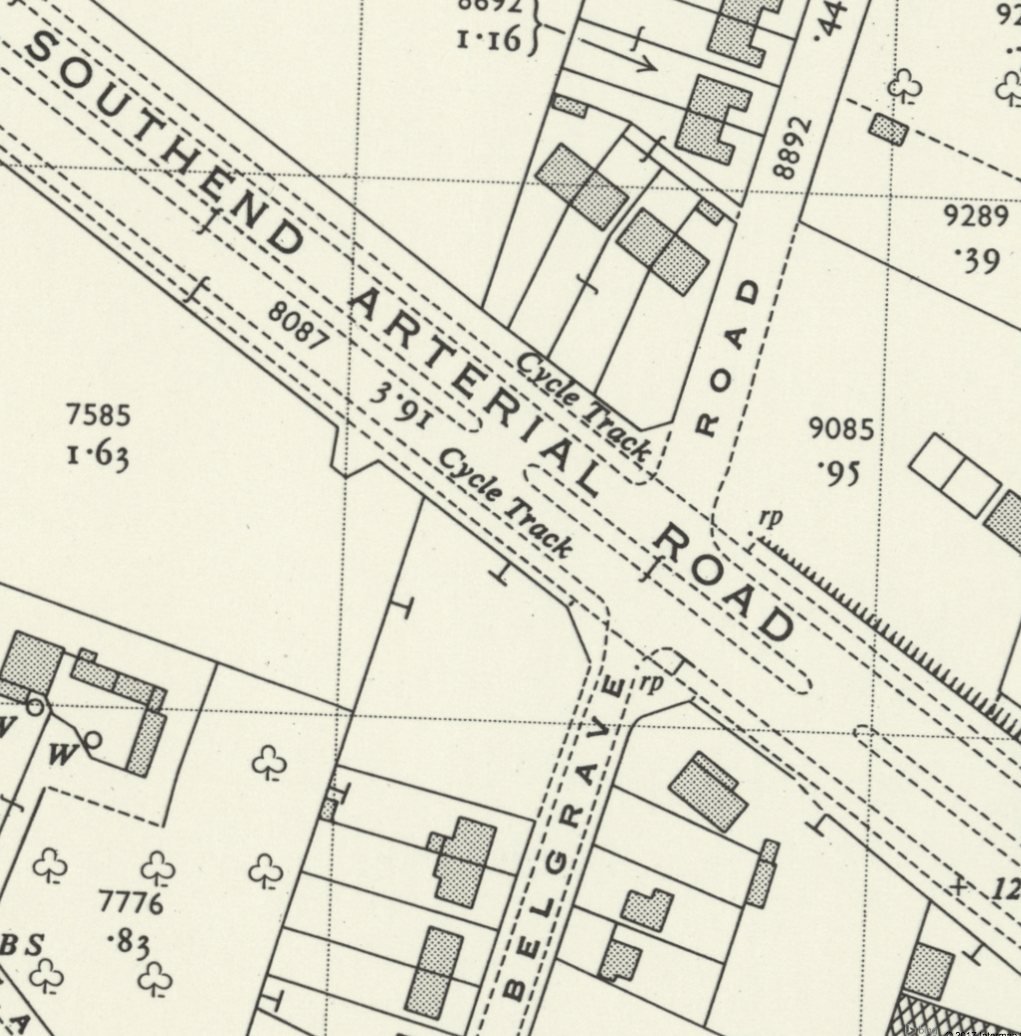

Before starting research on the book, Reid knew of the existence of a handful of ‘30s-era bike lanes. But when he started studying the decade’s road-building policies, he found archival maps showing that as new arterial roads were built, they all had cycleways installed beside them. “Every one I looked at showed that there were cycleways built,” he said. “It was clear that there were far more than anyone had understood.”

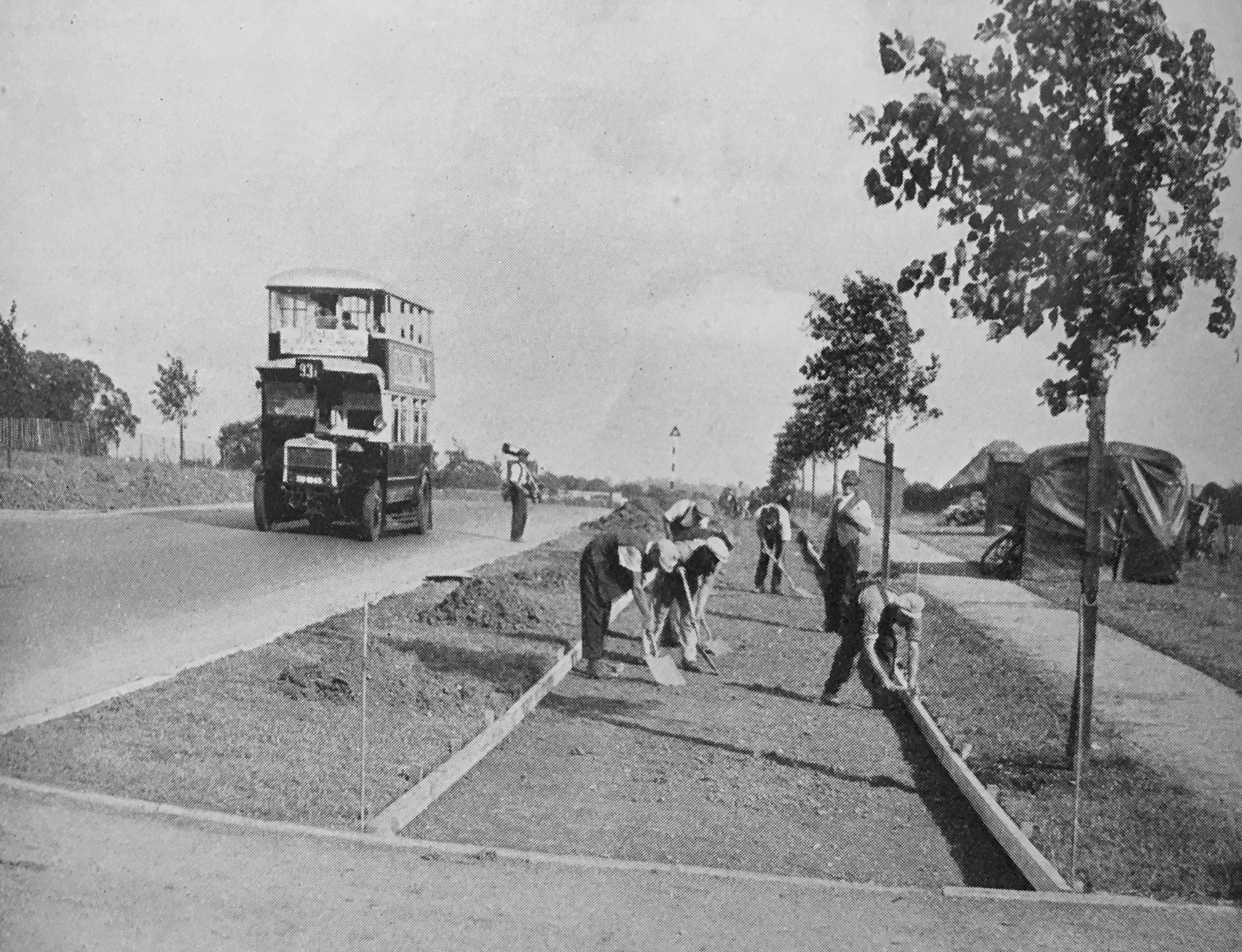

These bike highways were nine feet wide and surfaced in concrete, and they ran along major roads for miles. According to Reid’s research, the Ministry of Transport was inspired by newspaper reports of similar lanes in the Netherlands and contacted the Rijkswaterstaat, its Dutch counterpart. The head engineer of the Rijkswaterstaat sent the Brits “these incredible exploded diagrams of how they built cycleways next to the road and the railways and how they separated the traffic,” says Reid. “The Brits, in effect, were ‘going Dutch,’” decades before that phrase became a mantra among cycling enthusiasts who long for infrastructure as good as Amsterdam’s.

In the 1930s, cycling in Britain was at its peak, and cyclists far outnumbered motorists. As in America, it was British cyclists who first pushed the government to build smoothly paved roads between cities. Those roads, though, were catnip to motorists, too, and “motorists, if they wanted to use their cars and go fast … clearly had to get cyclists off the road.” These bike highways were intended in part to separate cyclists from the main rush of traffic and clear the way for drivers.

As more people bought cars, politicians grew increasingly concerned about cyclist and pedestrian safety. “The government was saying, ‘Yes, we want to get cyclists off the road so we can drive’—because the politicians were motorists—but also we have to save our citizens,” says Reid. “There was a definite idea of keeping people safe. It was both.” But plenty of cyclists at the time didn’t want to be siphoned off onto these bike-specific lanes. “There were all sorts of major campaigns against this infrastructure from hardcore club cyclists,” Reid says. But those who just wanted to commute to work or ride out of the city on weekends on two wheels were happy to use them.

In the years that followed the construction of the cycleways, though, cars became the predominant form of transportation, and the bike lanes fell out of use. Even the Ministry of Transport forgot that it had built them. “Within 40 years, it had been lost in their own department that they were doing this,” says Reid. He read the ministry’s minutes going through the 1960s and found records of ministers saying that they’d never built anything like a bike highway before.

“You did do it! I’m just willing them—look, look in your own minutes!” says Reid. “You’ll see that you did do it.”

After Reid discovered the extent of the network, he went looking for the paths themselves. It happened that there were two examples within cycling distance of his home in Newcastle. When he first saw them, he couldn’t believe his eyes. They were unused but pristine. “You look at archive photos from the 1930s, and they just haven’t changed,” he says. “It’s the original surface, even.”

The knowledge that these paths were meant for bicycles, though, had been thoroughly lost. When he was exploring, Reid says, he saw cyclists come riding by on the skinny sidewalk, when the 1930s cycleway was right there. “They didn’t think it was theirs,” he says.

Not all of the original 1930s network remains. Some lanes have been resurfaced, and most of what was built in London has fallen to development. Reid estimates that about 10 to 15 percent of the original cycleways have been buried. And there are places where the original work is at least partially concealed. Reid heard about a major route from London to the coast, for instance, that was very popular for weekend getaways in the 1930s. On Google Street View, he saw slivers of concrete, a couple of feet wide, that run by the road for a while, then disappear, only to reappear farther up the road. “I know what that is,” he says. “I know what’s under there. You’ve got this five-to-ten -mile stretch that people had forgotten was there.”

Reid and his collaborator, urban planner John Dales, are raising money on Kickstarter to continue their research, with the goal of restoring some of the network to use. (With two weeks to go, they’ve doubled their original fundraising goal.) They’ve already heard from cities on the network with money to spend. “Some of these cities look as though they’d be excited to work with us,” Reid says. “We’re going to work with the willing first.” Soon, it’s possible that these decades-old cycling highways could once again be part of Britain’s transportation network.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook