The L.A. Alley That’s a Subtle Silent-Film Landmark

One of Hollywood’s hardest-working locations finally gets its due.

Silent film star Buster Keaton crafted movies by letting locations speak to him. Though Keaton is most often remembered for his infamous unflappability—his “Great Stone Face” never registered the chaos around him—what stands out about many of his films now, as they approach their centenary, is Keaton’s great use of space. His approach to screenwriting involved plotting a beginning and an end, without worrying about what happened in-between. He let a site inspire him; gags emerged from the particulars of the place.

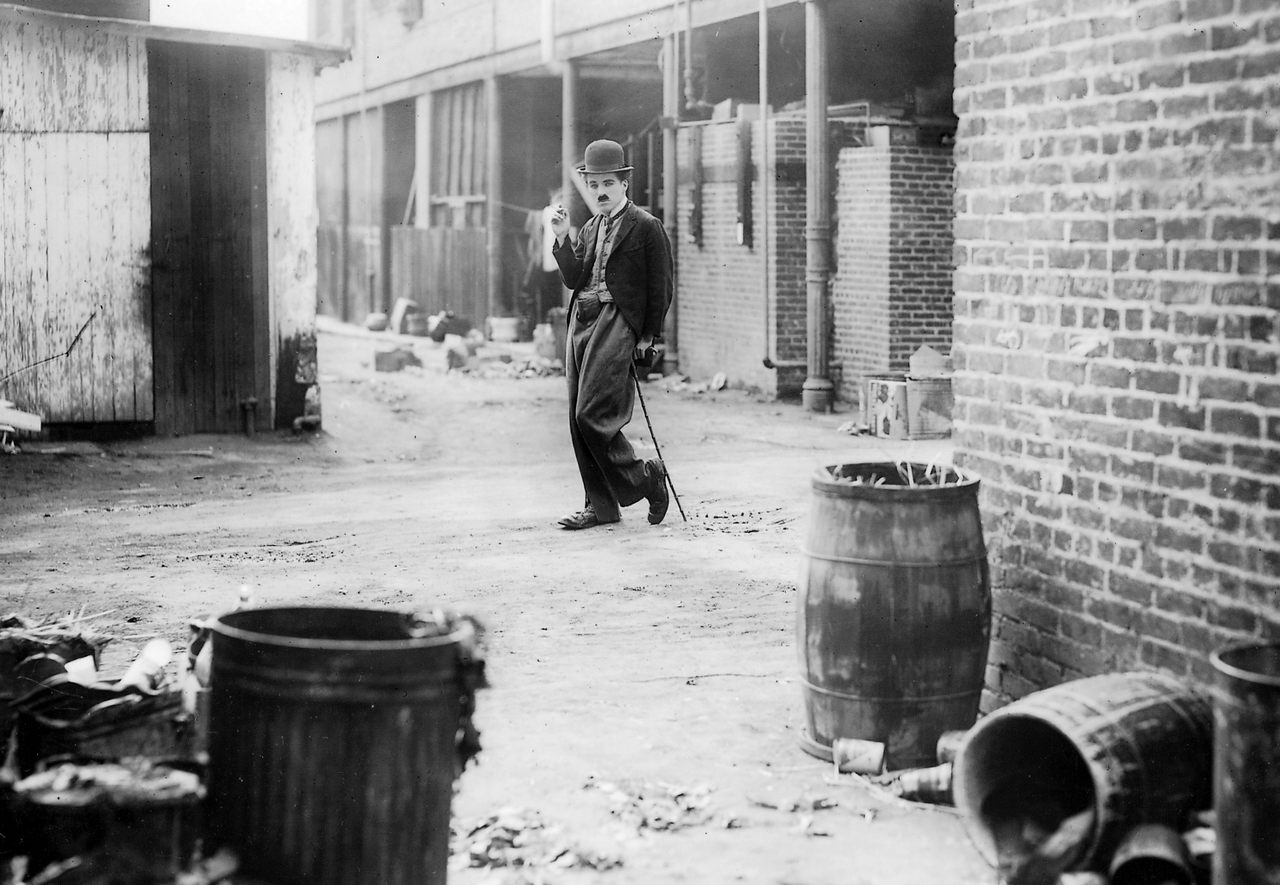

Keaton and fellow stars Charlie Chaplin and Harold Lloyd all played with space in ways that make it uniquely rewarding to find, visit, and study their filming locations. That’s why film historian John Bengtson’s project to locate and commemorate the spaces where this silent comedy triumvirate filmed is especially illuminating.

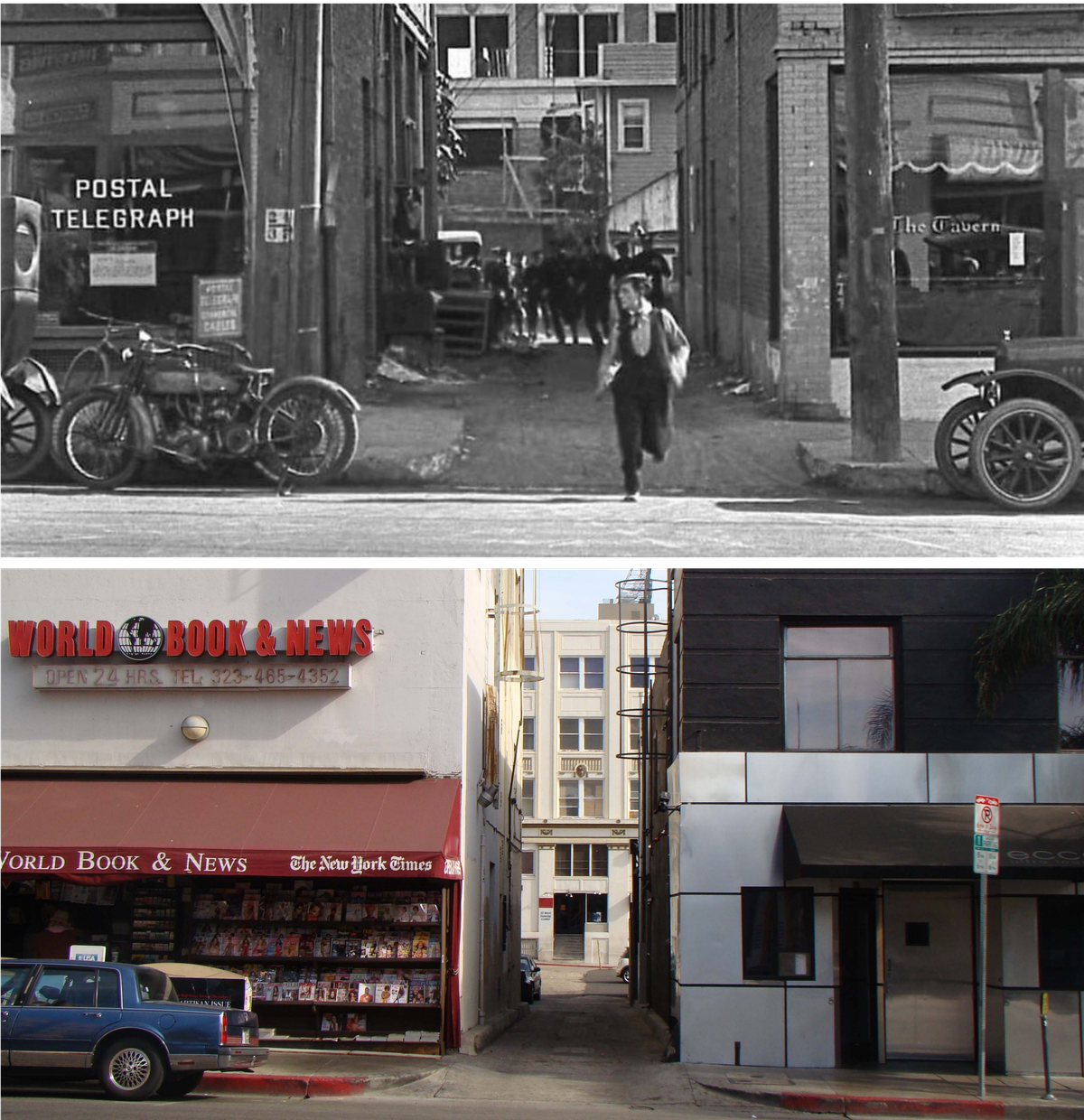

Bengtson’s most incredible discovery—a seemingly nondescript T-shaped alley in the heart of Hollywood—appears in numerous silent films, including three in the National Film Registry, movies preserved by the Library of Congress for their cultural, historical, or aesthetic significance.

The alley is the site of one of Keaton’s most memorable stunts in the 1922 film Cops. He runs down the alley with a drove of policemen in mad pursuit. When he reaches the end, he stops in the street, looking back at the clumsy mob stumbling after him. A car passes and Keaton grabs hold, flying offscreen behind the vehicle. Compared to some of his more elaborate stunts, it’s fairly simple—but it became one of his most iconic spectacles.

The place where Chaplin finds the titular kid he adopts in his 1921 masterpiece The Kid is just down the alley, a stone’s throw from where the cops chased Keaton. Harold Lloyd also creeps round the alley in an attempt to tardily sneak into work in his Safety Last! (1923). Those three movies in the National Film Registry are just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to films shot in the alley. It appears in two other Keaton shorts—Neighbors (1920) and My Wife’s Relations (1922)—as well. Pioneering director Lois Weber beat the boys to the spot, filming Where Are My Children? in the alley in 1916, the same year Cleo Madison set Eleanor’s Catch there. It also showed up in the serial The Purple Mask (1917), the Al Christie comedies Hubby’s Night Out (1917) and All Jazzed Up (1920), Gale Henry’s The Detectress (1919), a star-vehicle for illusionist Harry Houdini called The Grim Game (1919), Ben Turpin’s Ten Dollars or Ten Days (1924), and a newspaper drama from 1925, The Last Edition.

As a filming location, the alley had a lot working in its favor. Because it runs east-west, it was well-lit all day, and it was fairly quiet, Bengtson says. And in an era when studios were expanding, much of Hollywood was still orchards, open lots, or vacant fields; there weren’t many urban-looking intersections to choose from. For a period, he adds, “it was essentially the only alley in town.”

Bengtson—whose books Silent Echoes, Silent Traces, and Silent Visions retrace the steps of Keaton, Chaplin, and Lloyd, respectively—began his film location research in the mid-1990s when he noticed that a chase scene from the 1922 Keaton short Daydreams had been filmed in San Francisco, not far from where he lived.

When Bengtson visited the Daydreams locations, he noticed that things looked a lot different. One scene near Lombard Street—now famous for its eight hairpin turns—had been shot before construction began, so those attributes didn’t yet exist. “That kind of blew me away, because I realized there’s actually some history going on,” Bengtson says. “It’s not just the same place then and now.” The film froze a place in time, while the real-world spaces developed, changed, and aged.

Not long after that initial discovery, Bengtson was browsing vintage photographs of Los Angeles in an archive when he noticed a picture taken near the intersection of Hollywood and Cahuenga Boulevards. In the photo, just south of the intersection was an alley with some signs on either side of the entrance. He recognized it immediately as the backdrop of Keaton’s Cops car-grab stunt. When Bengtson was finally able to visit the alley months later, to see if it was still there, he found that it looked largely the same, and that it was also the site of another scene from Cops, in which Keaton’s hand is bitten by a dog. That sequence was filmed at the other end, the top of the “T,” where the alley hits Cosmo Street.

Before Bengtson’s rediscovery of the site and his work cataloging the silent films that utilized it (which he chronicled in his books and continues to describe on his blog, Silent Locations), the alley had gradually faded from collective memory. Though it appears in Tim Burton’s 1994 movie Ed Wood, Bengtson thinks it’s unlikely Burton knew the alley’s place in cinema history. “My sense is this was not an homage, but simply an expedient, true Hollywood locale,” he says.

Bengtson wanted an homage to the site, and advocated for the city to celebrate the history by naming part of the passage for the Hollywood luminaries who found inspiration there. He spread the word on his blog, where he offers free PDF guides for DIY walking tours of the nearby filming locations, and produced a video about the alley, which is now flanked by chic restaurants, cozy lofts, and office space. He emphasizes that he doesn’t want to rename the longer north-south segment, which runs parallel to Cahuenga Boulevard. That portion already has a name—East Cahuenga Alley (or EaCa Alley for short)—and it’s become a hip hangout spot thanks to the EaCa Alley Association’s revitalization of it.

Now the perpendicular part of the alley has a name, too—Chaplin Keaton Lloyd Alley—and permanent place in Hollywood history as, according to the crowd-funded plaque, a location where “three of the greatest comedies of all time were filmed.”

There are a few other sites where the paths of Chaplin, Keaton, and Lloyd all crossed—on a bluff in Santa Monica and at a long-since-destroyed Pasadena train station—but this place is special. “I can absolutely guarantee you that there is no place anywhere that has three of the biggest stars and three of their most important movies in one spot,” Bengtson says. “This is absolutely two or three strata above anything else I’ve ever found.”

This story was updated to include information about the alley naming.

This story originally ran in 2021; it has been updated for 2022.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook