The Chart That Measures Tall Trees Against Architectural Wonders

A 19th-century infographic that stacks a redwood against St. Peter’s Basilica.

Eduard Mielck was a big fan of enormous plants. He worked as a forestry official in Holstein, Germany, and in 1863 published a volume titled Die Riesen der Pflanzenwelt, or The Giants of the Plant World, which compiled measurements and dreamy illustrations of some of the most soaring living organisms known at the time.

Just how big is “giant”? It’s hard to understand height without a reference point—something familiar that sticks in the mind’s eye. Mielck understood this need for scale, and filled his book with illustrations that offer fresh perspectives on massive living things that relatively few would ever be able to see in person.

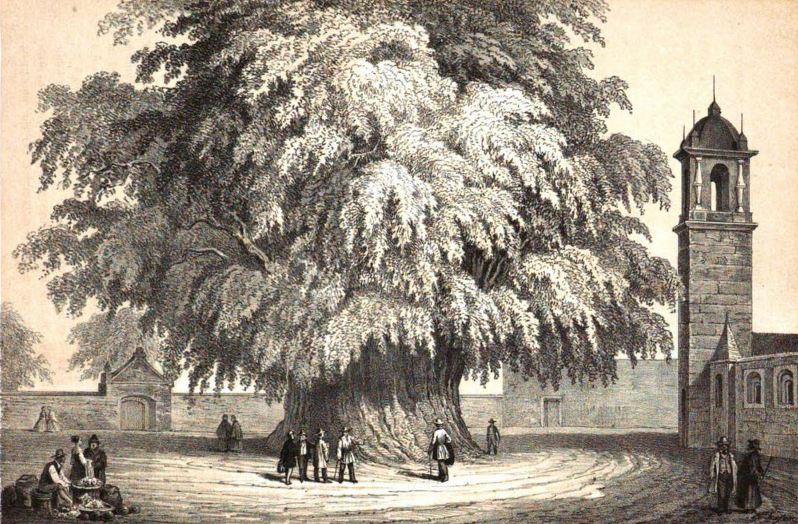

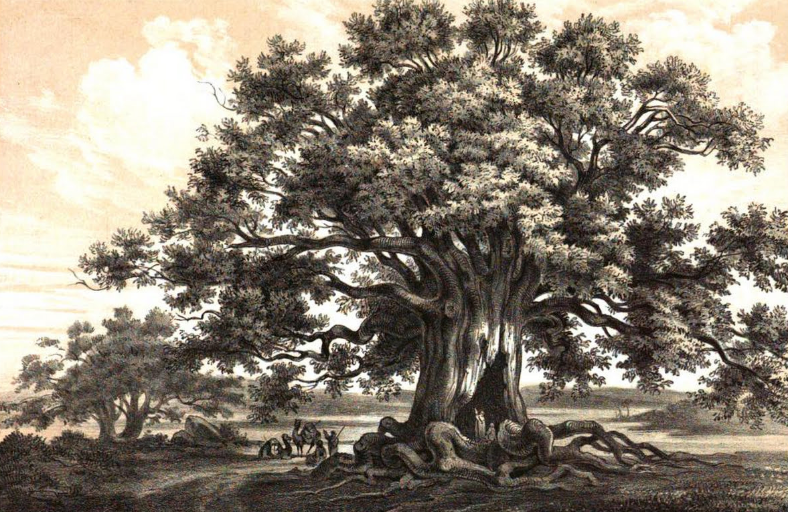

His images often included humans, humbled and awestruck, heads craned back to survey a swooping canopy. A man and his canine pal nearly vanish next to a grand oak from a forest near Oldenburg. Mielck illustrated the ancient, expansive Hundred Horse Chestnut in Sicily, with heartwood so hollow that several people could shelter inside the trunk, and a canopy big enough to have purportedly shaded 100 knights. A camel’s humps are barely distinguishable beside the undulating roots of a baobab tree in Senegal, and it would take a slew of people to form a ring around the Árbol del Tule, a monumental cypress tree near Oaxaca, Mexico, that ranks among the thickest in the world.

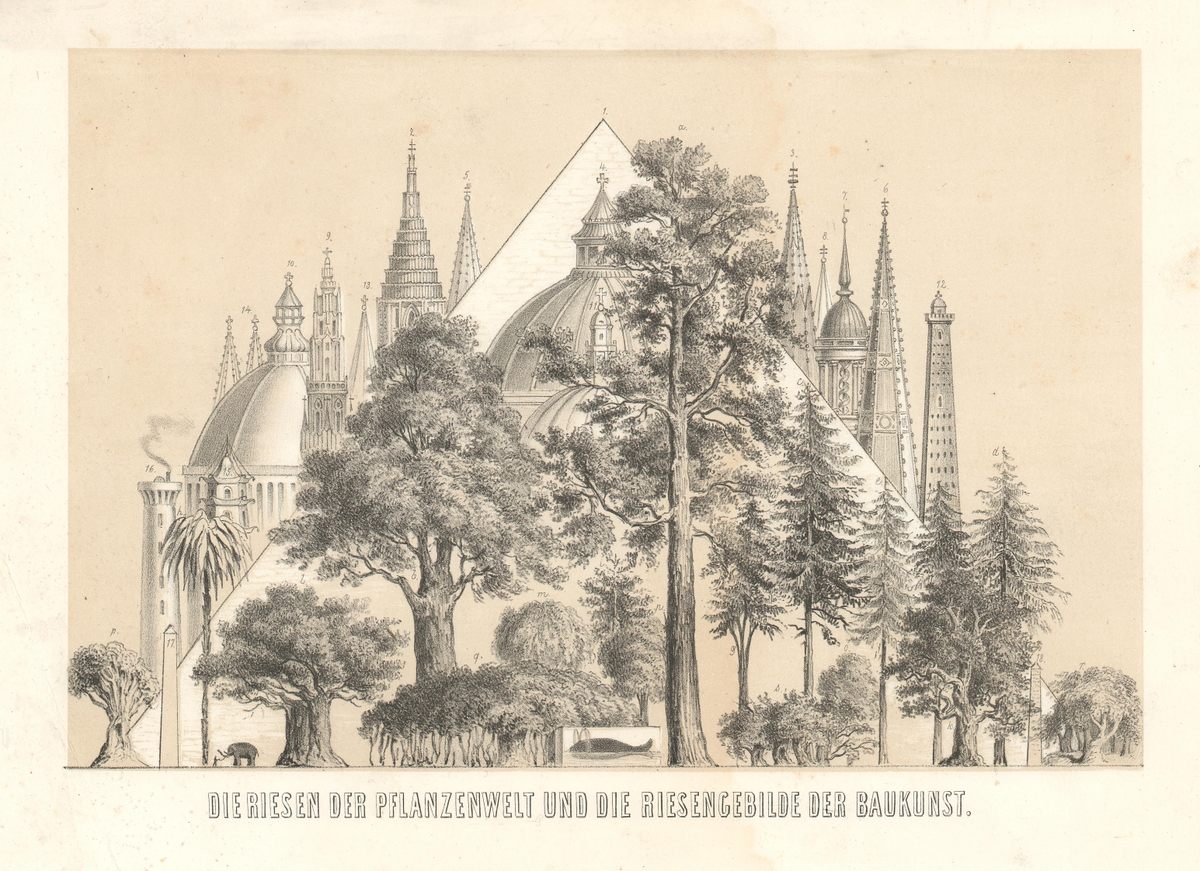

Then again, even modestly large trees dwarf people, dogs, and camels, so to really drive home the idea of enormity, Mielck created a chart that compares some especially towering trees to some famously big buildings.

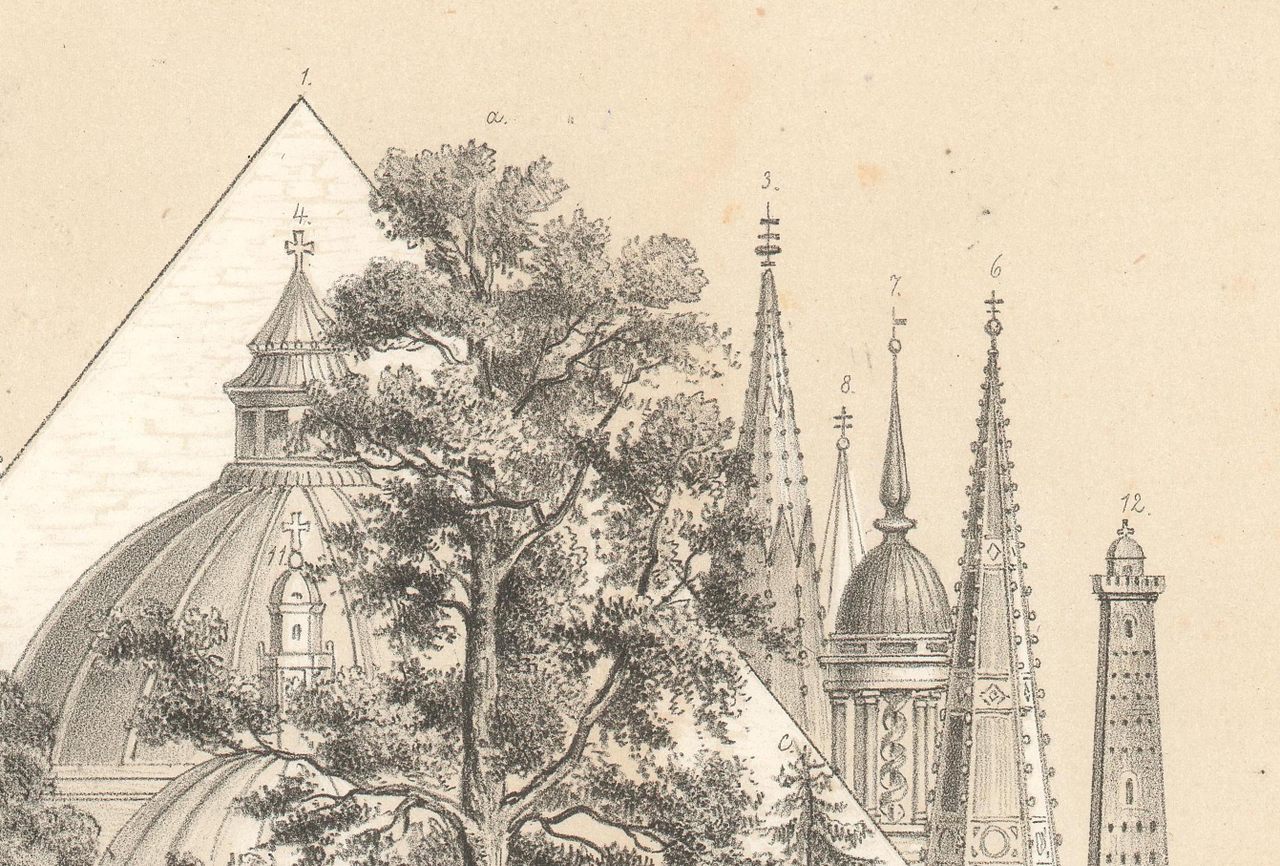

On a single plate, Mielck planted an imaginary forest where sequoias sprout near palm trees and cypresses, and iconic spires poke up behind their canopies. He called it “Die Riesen der Pflanzenwelt und die Riesengebilde der Baukunst,” or “The Giants of the Plant World and the Giant Structures of Architecture.” The chart is illustrative, if not always a clearly literal accounting of the real world.

On Mielck’s chart, the sequoia—labeled “ein Mammutbaum in Kalifornien”—is the tallest tree, just slightly shorter than the Great Pyramid of Giza. In the real world, the pyramid is taller by a wide margin—the tallest sequoias grow to around 275 feet, while the pyramid is around 455 feet—so the closeness in height is either a creative liberty or a trick of perspective. The same goes for the 448-foot-tall dome of St. Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City.

The math doesn’t always work out. The Luxor Obelisk in Paris, which is around 75 feet tall, could easily be surpassed by a Lebanese cedar, which can exceed 100 feet. On the chart, Mielck placed them next to each other, with the obelisk a hair taller. But the spirit comes through clearly—some trees are leggy, others squat, and many are really, really tall.

The chart is an example of the 19th-century fascination with quantifying the natural world and stacking up its wonders against one another—and against human accomplishment. That century, which saw a boom in precise measurement of natural features, also saw cartographers plotting imaginary landscapes of the world’s longest rivers winding in parallel or the planet’s tallest peaks sharing a single range. Mielck’s trees sprout on several continents, so they’d never be neighbors, and they wouldn’t share space with a crowded urban landscape. Still, it’s fun to imagine some of the planet’s most superlative specimens—natural and otherwise—all lined up in a row.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook