How a Brewer and the Government Killed Colombia’s Ancestral Drink

They conspired to replace chicha with clean, healthy beer.

The first time you try chicha, it might not be immediately clear why it was the object of intense devotion for several millennia. Frothy and milky in texture, the corn-based, alcoholic brew tastes a bit like the inside of a new shoe. But the drink, which was once ubiquitous in Colombia, has largely disappeared for reasons that have nothing to do with flavor. Instead, it was the victim of a relentless, decades-long marketing campaign waged by a German beer conglomerate and the Colombian government.

Chicha may be an acquired taste, but Colombians had a long time to get used to it. Archeologists have evidence that the drink was ritually consumed by the pre-Columbian Muisca people since at least 3000 B.C. It was both a sacred offering—often accompanying human sacrifices—and a drink of the common people. If you’ve traveled elsewhere in Latin America, you may have noticed that chicha is widely available; it’s popular from Honduras down through the Amazon basin (often as a non-alcoholic alternative). But only in Colombia did it come to symbolize vice and disorder, making it the bête noire of the government.

So what is chicha, exactly? Modern recipes vary by region, but the overall process is pretty consistent. Most varieties are made with maize or cassava, which women (always women) pop into their mouths and chew for hours. This part—the chewing—plays a key role in the fermentation process, since enzymes from saliva convert the starch to sugar, which, when combined with wild yeast or bacteria, eventually becomes alcohol. The preparers then spit the resulting juice into a clay pot, where it ferments for several hours. After that, voila: Chicha is born.

The process can be off-putting to newcomers—a group that once included the Spaniards who colonized modern-day Colombia. When they arrived in 1499, chicha was stripped of its sacred associations, becoming instead a drink of the working classes. According to Jeffer Carrillo Toscano, an anthropologist who works as a tour guide in Bogotá, the Spaniards sought to supplant chicha with their tipple of choice: a powerful, clear liquid called aguardiente, or fire water. They succeeded, to an extent. The anise-flavored liquor flows freely in bars and nightclubs, and is seemingly responsible for 80 percent of the nation’s hangovers.

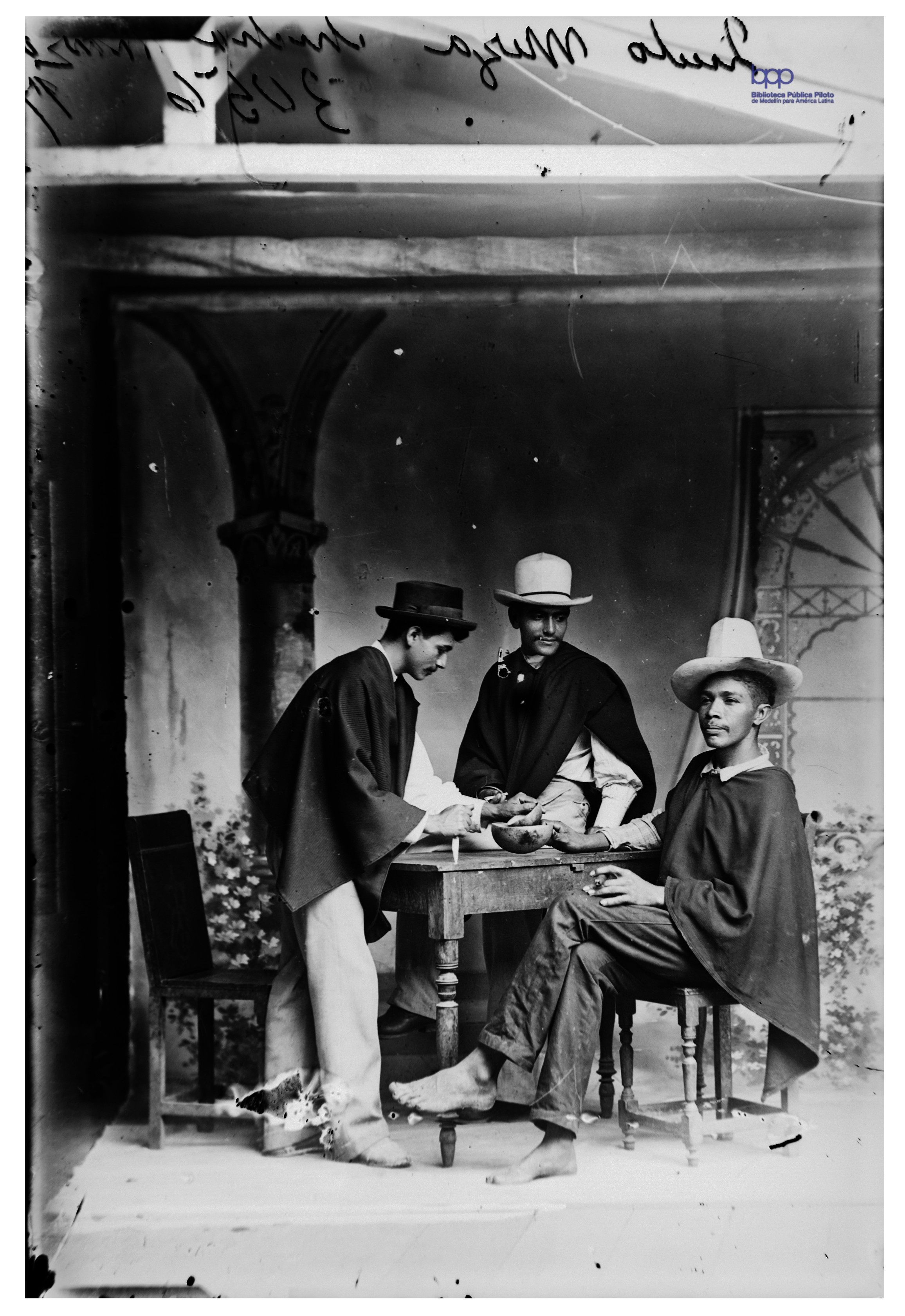

But chicha remained popular, and continued to be served by the gallon in dedicated spaces called chicherías. Think of chicherías not just as bars, but as homes-away-from home, where patrons could socialize over dice and cards. According to Toscano, they also served as hotels, restaurants, and grocery stores. Chicherías were, as he put it, “the place where poor people had everything they needed.” The experience was also deeply communal, with one large bowl of chicha generally passed among tablemates.

By the end of the 19th century, there were more than 800 chicherías in Bogotá alone. This is partially because the lifestyle of chicha’s primary drinkers—artisans and farmers—didn’t adhere to a 9 to 5 work schedule followed by a nightcap. Work and leisure were woven throughout the day, with long midday periods dedicated to relaxation and, of course, chicha.

“We’re talking about people who were owners of their own time, who didn’t have to follow a schedule,” Toscano says. “For these people, time was not money.”

Between around 1910 and 1920, poverty in Colombia was rampant—education, medical attention, and decent food were luxuries. But few Colombian politicians addressed these problems. As the historian and former politician Juan Carlos Flórez writes: “The powerful did not consider the appalling living conditions of the lower classes to be a problem that could be solved through social reforms.” Instead, he argues, politicians “were already more interested in the distribution of bureaucracy, state contracts, and their perpetuation of power.”

Rather than confront the root of these issues, Colombia’s body politic took a different approach: Blame chicha. For everything. Chicherías came to viewed by the ruling class not just as hotbeds of public disorder, but the single impediment to Colombia’s rise as an industrialized economy. The bulk of Colombia’s poor were indigenous people, who were, as the openly racist theories of the time dictated, a drag on progress.

“[They] represented an indigenous past, a legacy they wanted to get rid of,” says Toscano. Or as Florez bluntly phrased it: Chicha drinkers were considered “smelly Indians, illiterate, threatened by syphilis and possessed by chichis,” a disease more powerful than mere alcoholism.

That might seem like an awful lot to attribute to a drink made of chewed corn. But chicha—with its ancient heritage, association with unstructured work days, and production method of chewing and spitting—made a convenient symbol for the country’s problems. Chicherías became the enemy, with a shimmering, modern Colombia possible only once the last one was vanquished.

Still, total eradication proved a formidable task. Chicherías were too popular; their importance inextricable from the daily lives of the lower classes. And that’s when Bavaria Brewery entered the picture.

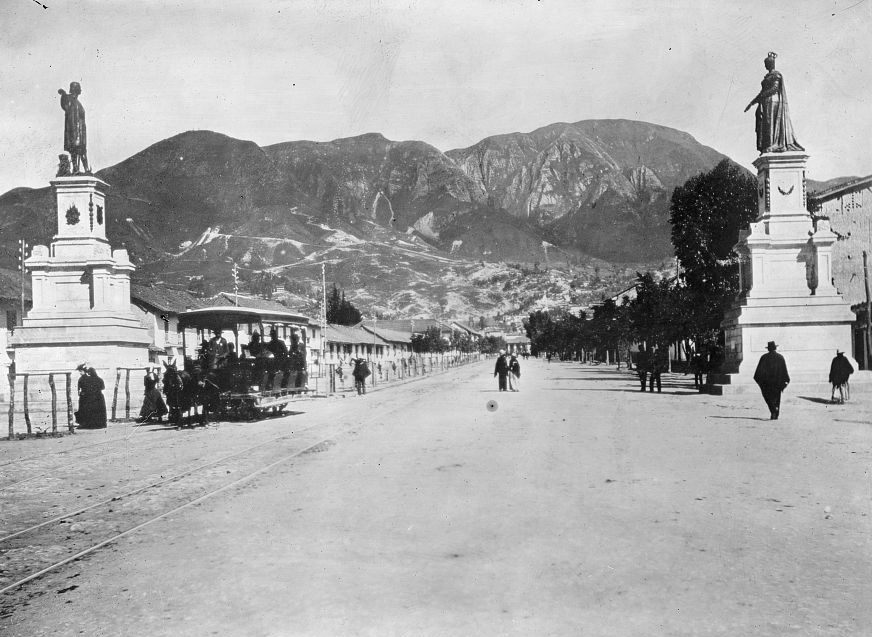

Bavaria was founded in 1889 by Leo Kopp, a German immigrant who purchased a plot of land in Bogotá and built a brewery in record time. Breweries existed around Colombia prior to Bavaria, but Kopp quickly established dominance in the beer market.

Beer and Bavaria Brewery were the spiritual opposite of chicha and chicherías. The brewery buildings were, as one writer put it, “a perfect example of 19th-century German industrial architecture,” and the factory whistle marked the passing day like a church bell. Whereas chicha was passed around in a bowl, beer was served in individual, sterile glass bottles. To Colombia’s post-colonial government, Bavaria Brewery, with its sleek machinery, regimented work days, and commitment to order, represented European progress and industry—a model they badly wanted to emulate.

Bavaria had no trouble gaining a foothold among Colombia’s bourgeoisie. But the majority of Colombians hardly had cash to burn on an exotic, expensive drink like beer—especially not when they had chicha. Chicherías remained everywhere, even in La Perseverancia, the Bogota neighborhood Kopp founded for employees of his brewery. But Kopp had an ally in the Colombian government.

Colombia’s political elite not only hadn’t abandoned its contempt for chicha; it was actively campaigning against it. Prominent doctors, likely at the behest of politicians, visited areas where the lower classes lived, pronouncing the drink “unhygienic” and a hazard to the country’s moral and physical well-being. They even invented an illness—“chichism”—which purportedly made its sufferers insane.

Between the chewing process and the bowl-passing, chicha may seem like a health hazard. But according to Dr. Patrick McGovern, the Scientific Director of the Biomolecular Archaeology Project for Cuisine, Fermented Beverages, and Health at the University of Pennsylvania Museum, fermentation by definition produces alcohol, and alcohol is an antiseptic. “If you have enough alcohol in there, it kills off all the bad bacteria,” he says. Hazards could potentially arise by letting it sit around, “but if it’s fresh, even if it’s one percent [alcohol], it’s probably safe.”

It’s unclear whether Kopp collaborated with the government, but he benefited from their position. Bavaria’s advertisements were even less subtle: Its beer came with names like “No Mas Chicha,” “Consum Bier,” and “Hygienic.” On top of that, Bavaria bombarded Colombians with images of robust, healthy-looking ladies and (rather sinister-looking) children, happily quaffing clean, life-giving beer, swaddled in the words “No Mas Chicha.”

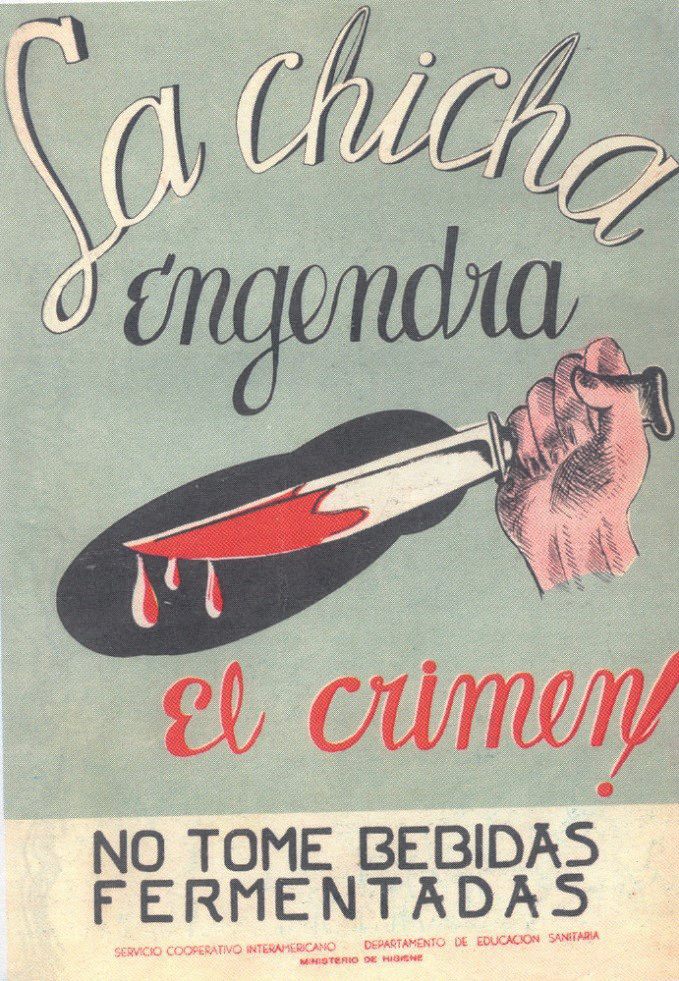

Not to be outdone, the government launched an aggressive propaganda campaign. “Chicha begets crime,” read one political poster, along with a filth-covered hand clutching a bloody knife. “The jails are filled with people who drink chicha,” read another, which features a nun weeping over a man peering out from behind bars. In another, two men brawl in a chichería while its toothless (and indigenous) proprietor shrieks with laughter.

The government also tightened its grip on chicherías in the form of increasingly unaffordable taxes and strict, arbitrary rules. Unable to comply, many establishments shuttered or moved underground. According to a 1921 entry in the Journal of the American Medical Association, “The city of Medellin has stamped out the disease by raising the license for the sale of chicha to a prohibitive figure.”

If chicha culture was on life support, the plug was abruptly pulled on April 9, 1948. On that day, Jorge Eliecer Gaitán, a liberal presidential candidate widely regarded by the working class as the country’s populist savior, was murdered on a Bogota street, kicking off a 10-year period of unrest known now simply as La Violencia.

The bloody riots that destroyed much of the city were the reaction to deep-seated social ills, but the government saw its moment to strike. On June 2, President Ospina Pérez signed a law declaring that all fermented beverages had to be industrially produced in individual glass containers—a de facto ban on chicha.

“At dawn on April 10 the commercial streets were in ruins, covered with corpses and excrement,” writes Florez. “That powerful and painful image … seemed to justify all racist prejudices.” Chicha became “the perfect scapegoat.” Thus, La Violencia claimed another victim: chicha, and the entire culture that came with it.

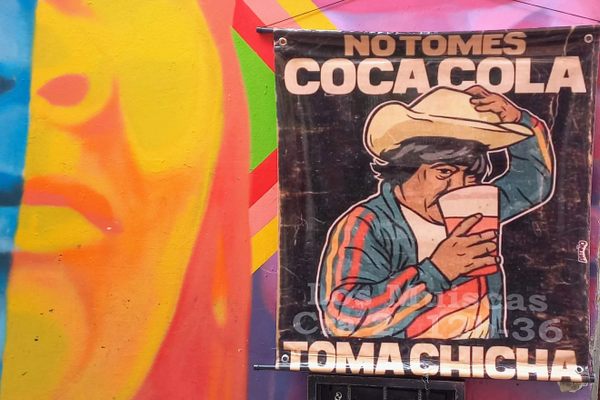

Colombia’s ills did not magically vanish with the death of chicha, and drinking beer and spirits did not make Colombia industrious and peaceful. But the campaign against chicha did deprive Colombians of a beloved drink, and the accompanying centers of social life.

Bavaria, for its part, continued to flourish, eventually cornering Colombia’s beer market. In 2005, it merged with SAB-Miller, a conglomerate that today produces nearly all of the country’s mass-market beer. In 2016, SAB-Miller was absorbed by Anheuser-Busch InBev. The corporation did not respond to a request for comment.

These days, Colombian chicha has been relegated to the stuff of myth, available only at the odd chicherías operating below the radar. I tried it in an out-of-the-way cafe in La Candelaria, Bogotá’s quaint, colonial neighborhood. Toscano says the experience remains a novelty.

It’s a strange outcome—a drink that’s cheap, easy-to-make, and has thousands of years of history is now hard to find. But that can happen when dishes or drinks become symbols of the things that most unite or divide us.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook