A Journey Into a Wondrous World Hidden Deep in the Congo Forest

A remote wedge of wilderness is home to trailblazing elephants, epic trees, and the only chimps and gorillas known to share a meal.

Excerpted and adapted with permission from John Reid and Thomas Lovejoy’s Ever Green: Saving Big Forests to Save the Planet, published March 2022 by W. W. Norton and Company. All rights reserved.

The ferry that carries cars, trucks, and people across the Sangha River runs only in the daytime. We were on our way back from a weeklong visit to one of the Congo’s most intact, wildlife-rich forest redoubts, called the Goualougo Triangle, which is separated by the Sangha from the country’s paved roads and towns. When we reached the crossing at sunset, we maneuvered around several trucks loaded with lumber, manioc, and charcoal. Across the water, lights were winking on in the small city of Ouesso. Our driver dismounted to chat with someone called “Manager” on the concrete ramp. Calls were made with people on the other side to see if the ferry could be prevailed upon to make another run; we had no apparent sleeping options on this side of the river other than crammed in our vehicle. To the east, a landscape of forests and wetlands—with scattered villages—stretched for hundreds of miles. Just as the sky ignited in a weave of salmon, red, and gray, we received the news that the ferry was done for the day.

There was an alternative: a boat called a pirogue that might still cross that evening. We drove a short way upstream to a village called Djaka, guided by Manager (this turned out to be his name, not a title). As we waited, a pickup truck dropped off a full load of passengers, who streamed down to the waterside with packages. A taxi delivered three beautifully dressed women with various children who all walked down to wait for the pirogue. A scholarly looking young man in wire-rimmed glasses appeared, carrying a goat, and proceeded down the hill. We asked Manager if perhaps we shouldn’t heave our suitcases down the bank and stake out an advantageous spot in the mud to assure places on the pirogue. He brushed aside the suggestion at first and then, as more prospective passengers amassed, agreed, and we moved our hillock of belongings closer to the water.

At length, we spied the pirogue’s bow light as it approached the shore. It looked skinny. Like a canoe. The idea of all the well-dressed women and the dozens of other people milling about in the dark, as well as our party of four Americans and four Congolese conservationists, and the scholar and his goat, and Manager, all boarding this slender craft was preposterous. At Manager’s signal we hoisted our luggage and made our move toward the pirogue’s bow, which was now beached in the mud. There was a great deal of shouting in French and Lingala, the regional lingua franca, but no shoving or elbowing. In fact, there was room to walk in the pirogue, with wooden benches along each side.

The pirogue continued absorbing the crowd from the bank. A boy passed by with a saucepan of gasoline and handed it to a committee ministering to the motor by flashlight. Shouting continued. The women commanded people to move back, stand up, switch sides. Eventually the beach was empty, with the pirogue’s bow firmly stuck on it. One last bout of standing up, sitting down, and shifting of humans toward the stern set us free. The motor purred as the pilot maneuvered the long canoe out of Djaka’s swimming hole, past the ancient trees, and toward the main current of the Sangha. The stars and night air and maybe a touch of fear among the nonswimmers charmed the passengers into silence. Several phone screens dotted the boat’s length with pools of light. The boat was a single piece of wood around 65 feet long and 5 feet wide.

To make a good pirogue, you need a tree much longer than that, at least 120 feet of trunk, to avoid cracked and twisted bits, and a 6-foot diameter. This one was Nauclea diderrichii, whose wood is heavy and resistant to rot and insects. The tree was hollowed down to a flat floor, leaving a dense, reassuring keel below.

Few forests in the world have trees big and straight and heavy enough to make a pirogue that can carry six dozen humans, plus cargo and animals, across a big river. The woods in the north of the Republic of the Congo, a country that neighbors the much larger Democratic Republic of the Congo, is one such place. Of the world’s tropical forests, the Congo has the biggest trees by volume. As soon as you walk into the woods, you’re among giants. Finlike buttresses flare at the bases of some. Others emerge fat and round straight from the earth, as if their boles extend far underground before eventually giving way to roots. For one accustomed to the Amazon’s weave of palms and vines, the Congo forest is immoderate, grand, and vertical.

This is the planet’s second-biggest rainforest. The Congo basin contains half a billion acres of moist tropical forest and another 250 million acres of fringing secondary forest and dry woodlands on the adjacent plateaus. Around 60 percent of the rainforest is in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, around 10 percent each in the Republic of the Congo, Gabon, and Cameroon, and minor shares in the Central African Republic and Equatorial Guinea. The western Congo has Africa’s biggest populations of forest elephants and great apes, along with various other primates, forest antelopes called duikers, and a safety-vest-orange, floppy-eared wild pig.

Our guide for the trip to the Goualougo Triangle was Dave Morgan, who got his start in zoos. In 1996, Morgan joined a biologist named Mike Fay, who was managing the Nouabalé-Ndoki National Park in northern Republic of the Congo. Morgan initially worked near the Goualougo Triangle, but not in it. That’s because Fay had declared the area off-limits even to research. When Fay had wandered out there in 1991, he found “naive” chimps and gorillas, a primatology term for apes that have no previous experience with humans. They didn’t run away from Fay or try to run him off. Fay wanted the Goualougo Triangle to stay innocent.

But in 1999 a logging company was poised to start operations near, and perhaps even in, the Goualougo Triangle. The biologists were faced with the reality that the forest jewel would be logged if they didn’t occupy it. As part of a pragmatic deal struck with the logging firm, Morgan was tasked with setting up the Goualougo research project.

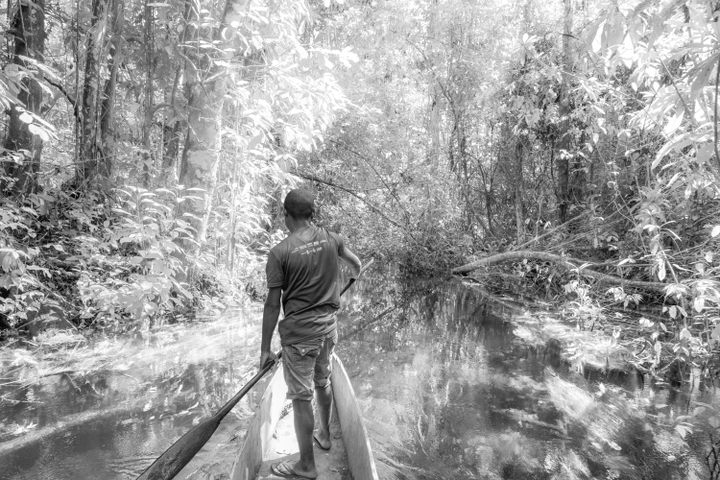

To get there we drove for two days from the capital Brazzaville, managed to catch the same ferry across the Sangha River that we would narrowly miss on the return journey, and drove three more hours on orange dirt roads that narrowed until the bushes slapped the Land Cruiser’s mirrors on both sides. At the road’s end, we climbed into small pirogues and wound our way up the slow and swampy Ndoki River and then the smaller Mbeli, under tree arches in a channel that smelled like a garden and dwindled in spots nearly to the width of our canoes. After an hour we disembarked and started walking on trails made by elephants.

These smooth paths bend elegantly this way and that, converging at four- and six-way crossroads. Following one of these trails, you can almost imagine an elephant’s day, visiting one tree after another. Furry octagonal Duboscia macrocarpa fruits are chewed and scattered. The next tree announces itself with a burnt-sugar-and-cherries aroma. Long reddish-black pods of Tetrapleura tetraptera, a local cure-all, are strewn half-chewed on the trail and in the bushes all around its base. Elephants cut the trail to this tree, but gorillas love the seeds, too, inserting a canine and running it the length of the capsule. The sticky pods might simply taste good, but gorillas and elephants, like many other species, are known to use plants medicinally. Further along, we come upon a “scratching tree,” deformed and stuccoed with red dirt that elephants throw on their backs and rub off on selected trunks.

Forest elephants are a separate species from those that roam the savannas. Loxodonta cyclotis is adapted to moving through the woods, with smaller bodies and straighter tusks than L. africana. What really hits you after walking on their trails for a while is a realization that they engineer the entire forest for the mobility of other species, including us. We found leopard and forest buffalo droppings on the trail and smelled the cotton-candy-scented pheromone emitted by red duikers. Chimps, gorillas, bongos, various other antelopes, and wild pigs all use the elephant paths to get around.

Six hours’ march brought us to a place where the trail disappeared underwater. It was a river inside of the forest, a swamp with a current, and our final obstacle before reaching camp. We took off our shoes and waded into the Zoran River. The water cooled our ankles, then knees, then hips as we quietly immersed and moved in a line, feeling our way tentatively in the opaque coppery water. The bed was smooth and sandy in places, padded elsewhere by mats of leaves. Unseen roots and logs were navigated via a friendly system of hand-signaling to the next person in line. Before the wade, Dave Morgan had recounted crossing a similar river in the Goualougo Triangle one day when something in the dark water suddenly bolted through his legs. When it surfaced, he caught a glimpse of a water chevrotain, a striped and spotted dog-sized deer, known to hide from predators in the water.

After 20 minutes, we walked out of the swamp, a little sorry it was over. We laced up our shoes and after a few more minutes were ducking under an elephant fence—wires festooned with empty sardine cans—that forms the perimeter around the Goualougo Triangle research camp.

Morgan has been around the apes for over two decades. He’s had every kind of encounter, including once when he “got slapped around” and sustained a serious gorilla bite to the shoulder. His peak moments are when he sees the primates do something unusual. Novel ape behavior expands the human mind and often shrinks the domain of what people have doggedly attempted to claim as uniquely human, such as humor, mourning, cooperation, planning, tool use, and other special things we do. In fact, apes do all these things. They tickle, prank, and laugh. In the first decade of their research at Goualougo, Morgan and his wife, Crickette Sanz, documented 22 different instances of tool use among chimps, including tools for feeding, self-care, first aid, comfort, and play.

Our first night in camp, Morgan explained that we might witness a behavior few humans have ever beheld: ape co-feeding, which is when two ape species eat together. Co-feeding involving gorillas and chimps was not known to occur a couple decades ago and is being documented exclusively here in the Goualougo Triangle, the only place in Africa with both chimps and gorillas that have been habituated to the presence of researchers. For days, Morgan’s team has been monitoring a massive Ficus recurvata, a fig tree about 30 minutes’ walk from camp that produces golf-ball-sized fruits. They smell like a smoothie made of green mangoes, cardboard, and cut grass. A botanical survey in the area found only one of these trees in every 1,500 acres. They fruit once every 13 months, and the chimps have the locations and dates marked on their mental calendars. In the days preceding our visit, the research teams observed a female chimp coming by several times to test the figs for ripeness, like someone squeezing supermarket peaches.

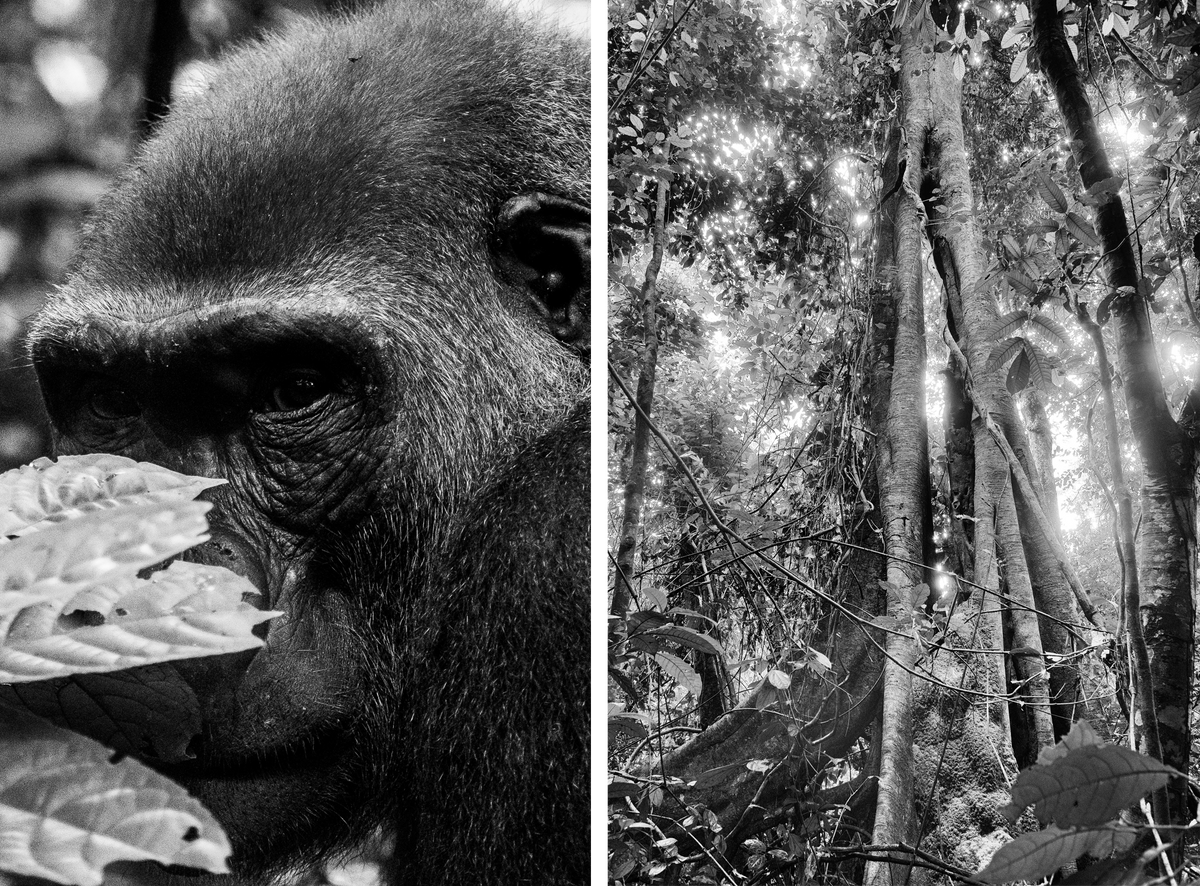

We set off before dawn the next morning. When we arrived, the fig tree held two gorillas and four chimps, plus some vivid green pigeons and noisy birds called giant plantain eaters. Co-feeding is not a lovefest. There is an obvious power imbalance. The chimps are canny, fast, territorial, and move in large communities. The group we met is called the Moto community, after the Lingala word that means both “fire” and “man.” It has 55 members, around half of whom were present. Gorillas live in smaller family groups, like the company of five we observed, led by a silverback called Loya. The chimps seemed, at best, to be tolerating the gorillas. The gorillas in the trees, Loya’s sons Mojai and Kao, ate with one eye on the fruit and the other on the chimps. At one point Mojai got into a pickle. Hugging a fat smooth branch, he slid down to the place where the fig tree first bifurcated, far above the forest floor. Soon there were chimps directly above him on both of the main branches, and the central trunk was too big for him to embrace for further sliding. He nervously looked for options. Eventually, the chimp on one of the exit branches moved off and Mojai scrambled up and into a neighboring tree. The rest of the gorilla family settled for fruits scattered on the ground.

This towering fig specimen draws the two ape species into a temporary bubble of intimate, if uneasy, coexistence. While in proximity, they benefit from each other’s alarm calls. The younger individuals will engage in cross-species play and even sexual exploration. There is chest-beating and sometimes violence. Gorillas are known to benefit from chimps’ awareness of ripening fruits and follow them to the trees. And the researchers are watching for any sign that the gorillas pick up on the chimps’ tool use. Nothing conclusive so far. Morgan also points out that what we watched was a dynamic that could very well have been part of the Pleistocene human experience, during which Homo sapiens had human contemporaries such as Denisovans and Neanderthals. “Bones can only tell us so much and seeing real behavior in the wild is instructive. All we have to go by at this point is sympatric chimpanzees and gorillas.” The term sympatric describes species that inhabit overlapping areas.

We moved away from the ficus with botanist David Koni to look for Loya. The silverback was asleep, sprawled on the forest floor. Koni is a plant savant, able to identify almost anything in the forest with his eyes shut. He whispered that when Loya woke up, the ape could reach out in any direction and find something edible, from the gorilla point of view. Like cows, gorillas ferment their food during digestion—in the apes’ case within oversized colons. They can eat just about anything green. As if on cue, Loya stirred, rolled, reached out a huge arm, and stripped leaves from a nearby bush. He munched, stood, and then ambled along an elephant trail, back to the co-feeding tree.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook