This ‘Satan’ Spider Turned Out to Be a Real Teddy Bear

In Ecuador, Satanas the tarantula—named for his feisty attitude—became both teacher and friend to researchers.

In the spring of 2021, Roberto León was hiking with some friends in a nature reserve high in the Andes. About two hours southwest of Quito, Ecuador, it is a scenic region known for its verdant rainforests and plunging waterfalls. But León, a biology student with a keen interest in the country’s undiscovered biodiversity, wasn’t there for the views. Instead, he kept his eyes trained on the ground.

“We were looking in cracks and crevices for anything—snakes, lizards, anything,” he says. Eventually, León’s gaze fell upon a bamboo fence, where he saw “two little legs sticking out.” He knew right away that they belonged to a big, furry tarantula.

After failing to lure the palm-sized spider out with a stick that he used to mimic prey, León began cutting away pieces of the bamboo—carefully—with his machete. The tarantula retreated further into the fence. Even when León had the spider cornered, it refused to surrender. Instead, “it sort of freaked out, ran around, and jumped directly at us,” León says. “My friend got the spider straight to the chest.”

León quickly plucked the spider from his wide-eyed friend’s shirt and placed it in a makeshift terrarium he had brought along for just such a discovery. He decided to nickname his new specimen Satanas, Spanish for Satan. “Not because it was an evil spider,” León says, “but because it was crazy and erratic. It was so unpredictable, it was like dealing with Satan.”

It was the first tarantula he collected as a member of the Mygalomorphae Research Group (MRG) at the University of San Francisco in Quito (USFQ), where León is now a senior. The mygalomorphs are some of the largest and most ancient spiders on the planet, including tarantulas. MRG’s mission is to document as many of Ecuador’s mygalomorphs as possible before human activities, including mining and agriculture, wipe them out.

“There is a research gap that’s gigantic in Ecuador,” León says, noting the country’s rugged and inaccessible landscape. When he joined MRG three years ago, no one—not even his biology professors—could identify the mouse-sized tarantulas he found on his family’s land outside of Quito. USFQ graduate student Pedro Peñaherrera had a similar experience. He founded MRG in 2019 to satisfy a “huge curiosity” born after receiving another unidentifiable tarantula as a pet.

Peñaherrera, León, and the other four members of MRG were undergraduates when they started scouring the countryside for unknown spiders, and soon their classmates were calling them the “Mygalobabies.” Their work is no child’s play, however; so far, they’ve described 16 species new to science.

Back to that feisty spider in the bamboo fence: It would take months before León could determine whether it was a new species. Before they reach sexual maturity, juvenile tarantulas tend to look alike, and are almost impossible to sex or classify. This meant that young Satanas would be taking up residence in the university’s zoology lab until he matured. It didn’t take long for the tarantula to defy his devilish reputation.

“Tarantulas have personalities,” says León. “A lot of spiders in our lab are evil and attack everything. But a lot of spiders are really nice”—including, it turned out, Satanas. León says his labmates quickly became enamored of the spider, choosing to do their work near his terrarium. “There’s a word in Spanish, simpatico, it means nice to be around,” he says. “It doesn’t quite translate in English, but he was nice to be around.”

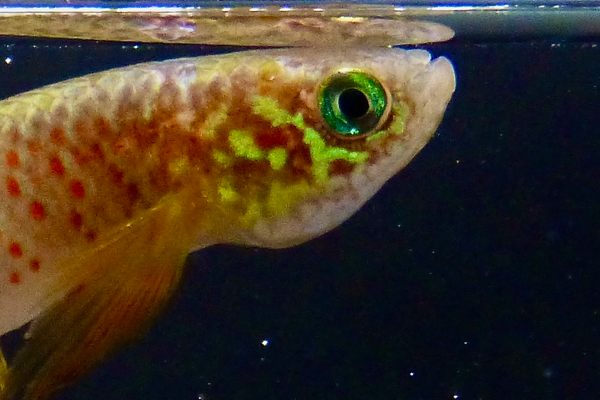

The team also got to see the spider’s softer side, literally. “All tarantulas are hairy, but Satanas was particularly hairy,” León says, “He was like a spider teddy.”

When allowed out of his enclosure, however, Satanas was still a bit of a wildcard.

“This was one of the first tarantulas we took photos of,” Peñaherrera says. “We still didn’t know how to handle tarantulas with our hands.” Instead of staying still on the white background, Satanas scurried away so quickly that “it was like he teleported.” Peñaherrera still laughs thinking about the team screaming and scattering at Satanas lightning-fast movements.

“This was the tarantula that taught us how to work with tarantulas,” adds León. Eventually, the group managed to wrangle Satanas—in a Tupperware container—for his photoshoot.

After a few months in the lab, Satanas finally reached maturity, molting into a golden-haired adult and developing papal bulbs—male reproductive organs that balloon out from the tips of the spider’s front legs like boxing gloves.

But just as the researchers were getting to know the grown-up Satanas, he died. While female tarantulas can live for up to 30 years, male tarantulas are not long for this world, dying shortly after reaching reproductive age at anywhere between one and 10 years old.

“Everyone was sad,” León says. But he and Peñaherrera were determined to classify the spider once and for all. By dissecting the tarantula’s papal bulbs, the researchers were able to confirm that Satanas belonged to a previously undiscovered species. To honor their furry friend, the researchers named the new species in his memory. Describing Psalmopoeus satanas in a Zookeys paper published in late 2023, the pair wrote that their team “grew very fond of this individual during its care”—a marked departure from the objective language typical of scientific research.

“They do become like pets to us, even though they’re not. They’re research subjects, but we become attached to them,” León says. He hopes Satanas—and all the other spiders he and his fellow Mygalobabies have discovered so far—will one day influence government policy around mining, development, and the illegal pet trade. The area where Satanas was discovered currently has no legal protection and is a hotspot for both illegal gold mining and wildlife smuggling. While León and his colleagues always secure the appropriate permits before collecting animals in the field, including Satanas, poachers do not, and stealing spiders for the ruthless exotic pet trade remains a constant threat for the animals.

“There are so many species we don’t know about,” León says. “But they’ll only be there for so much longer until anthropogenic activities take their toll, and they go extinct.” The true legacy of Satanas may be to inspire programs—and future generations of Mygalobabies—to discover, study, and protect these animals.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook