How Connecticut’s Homegrown Silk Industry Unraveled

The problems began with a new variety of mulberry and ended with lumpy thread.

In October 1789, during a trip to Connecticut, U.S. President George Washington described some “exceeding good” silk lustring and “very fine” silk thread that were part of a growing domestic industry. In fact, by the time Washington wrote those words in his journal, the area that became the state of Connecticut in 1788 had been practicing raw silk production, known as sericulture, for over half a century—and silk was on the rise.

By 1826, three out of every four households in Mansfield, Connecticut, were raising silkworms, and by 1826, Congress commissioned a report on the potential for a U.S. silk industry. By 1840, Connecticut outpaced other states in raw silk production by a factor of three. Within the next two decades, however, the industry would collapse, leaving the country to wonder what went wrong.

The unlikely development of Connecticut’s silk industry came about thanks Ezra Stiles, the seventh president of Yale University. Stiles was a sericulture enthusiast who experimented with cultivating mulberry trees, silkworms’ primary food source, and even wore gowns made from Connecticut silk to ceremonies. He also sent mulberry seeds and silkworm eggs across the state, and advocated for state-sponsored bounties to encourage farmers to plant mulberry trees.

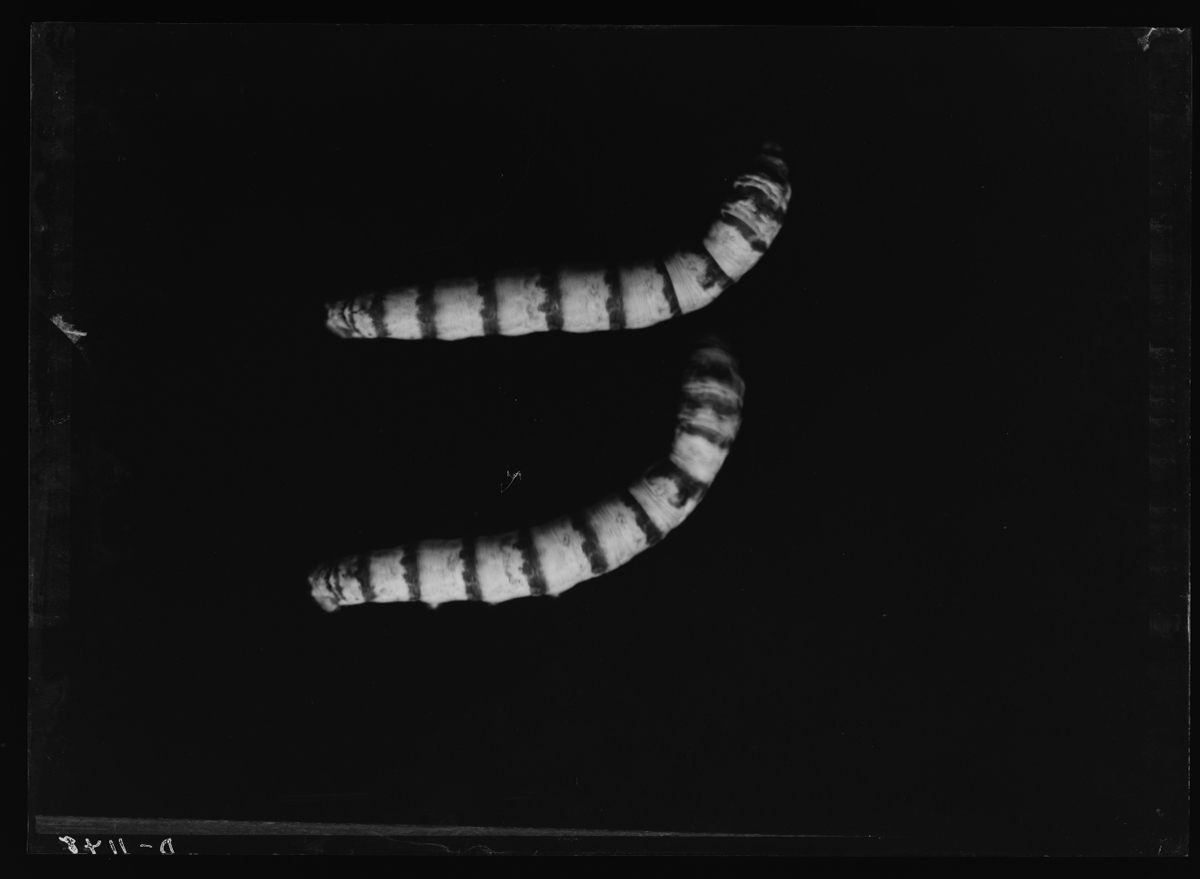

One of the biggest triumphs for the early industry was figuring out how to adapt sericulture to cold weather. Such tactics included keeping silkworms warm by raising them in attics, and figuring out how to feed them in cold weather. Michael Cook, a modern sericulturist, describes the intense care and feeding schedule silkworms require.

“Rise early, feed the worms before work; feed them again at lunch, feed them again in the evening and clean a dozen or so big trays, feed them again before bed. I was feeding a garbage bag full of [mulberry] leaves and small branches daily. Cocooning was a nightmare,” says Cook. In Connecticut with deciduous mulberry trees, that intensive feeding schedule was a problem in years with early frost. One innovation to extend the feeding season was to dry mulberry leaves, then mix them with water and flour to feed to silkworms.

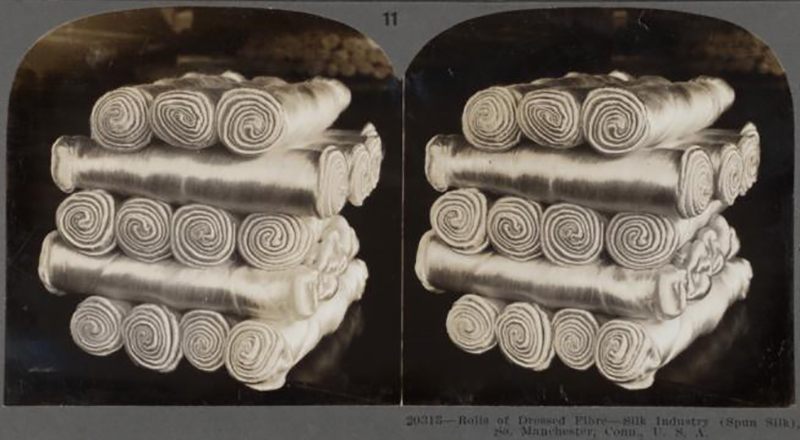

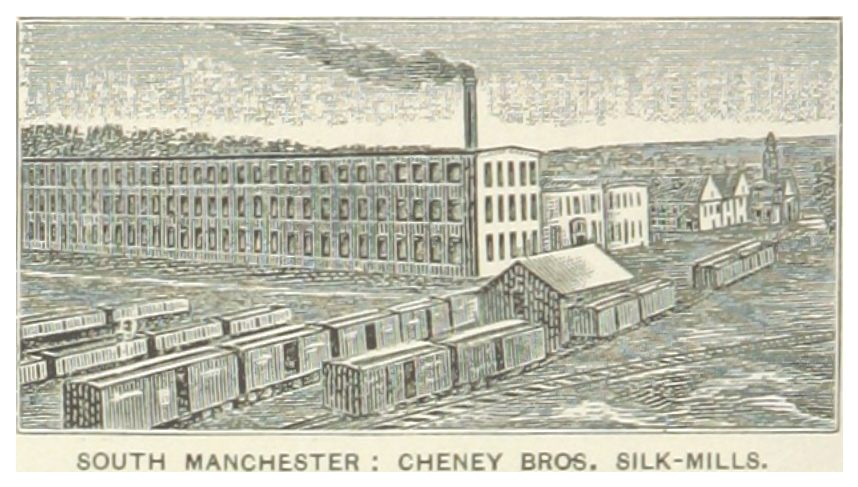

Inspired by Connecticut’s raw silk production, local entrepreneurs invested in machinery to manufacture silk thread and fabric from reeled silk filaments. In 1810, the Hanks brothers opened the United States’ first silk-mill in Mansfield, Connecticut, and in 1838, the Cheney brothers opened a mill which would eventually expand to 38,000 spindles, and become the largest silk manufacturer in the U.S. The future looked bright for silk.

The problems began with a new variety of mulberry and ended with lumpy thread. Beginning with Stiles, Connecticut sericulturists had always used an Italian variety of white mulberry, Morus alba, to feed their silkworms. However, in the 1830s, as the industry pushed to expand quickly, farmers and investors latched onto a Chinese variety, Morus multicaulis, a subspecies of black mulberry which produced larger leaves and more of them per tree (today M. multicaulis refers to a different plant, a subspecies of M. alba). It could also be harvested more often. The price of M. multicaulis skyrocketed as speculators sought to profit from selling cuttings from these fast-growing trees.

Samuel Whitmarsh, a “charismatic and unreliable businessman” who owned a silkworm cocoonery in Massachusetts, stoked the M. multicaulis craze with pamphlets trumpeting the benefits of this new type of tree, and letters to various silk trade publications. Daniel Stebbins, Whitmarsh’s business associate during the craze, later recounted the story of one tree that a speculator bought in Massachusetts for $25 and sold in Connecticut to a farmer named Elder Sharp for $50. Sharp then declined an offer for $450 for a quarter share of the tree; within a year the tree was worthless. The bubble had popped.

In the bubble’s aftermath in the early 1840s, companies along the East Coast went bankrupt, as did Whitmarsh, and angry farmers tore out their orchards. Joshua Grant, a silk producer in Baltimore, called the collapse a “dire disaster that has overspread the land like a funeral pall.” Then a series of harsh winters, followed by a blight in 1843-44, killed many of the remaining mulberry trees.

Despite everything, in 1847, Stebbins remained hopeful about the “sequel of the silk industry.” But the region’s sericulture had one insurmountable flaw that prevented this revival: Stiles’ gowns aside, Connecticut’s silk was not industrial grade, so silk-mills could not use it to manufacture fabric. According to cultural anthropologist Dr. Janice Stockard, who has interviewed silk reelers in South China, reeling—the practice of unwinding the filaments of silk from their cocoons—requires observation, training, and practice. In 19th-century Connecticut households, women were expected to learn the skill from pamphlets.

“In pamphlets, the term ‘spinning’ described the critical technique of reeling silk from cocoons,” Stockard says. “Women in farming households improvised, based on their experience spinning wool and using technology found in the home, including the wool wheel.”

The product they ended up with was adequate for sewing thread, but not strong enough for the industrial-silk-manufacturing infrastructure that Connecticut had begun to build. According to one scathing assessment, “Connecticut women in 70 years have not improved their knowledge of reeling.” Another issue, Stockard says, was the expectation that women could reel silk “whenever leisure from other duties permitted.” In other words, women were supposed to wedge a high-skill, time-intensive task into their already full workloads, and the result was sub-par silk.

“Simultaneously unwinding several cocoons from a basin of near-boiling water while twisting these filaments into one even thread and reeling it onto a wheel was hard,” Stockard says. “If reeling was interrupted to tend to a child or chore, the silk would gum up and lump.” Faced with this weak, lumpy thread, Connecticut manufacturers began to import raw silk from China, Japan, and Italy.

By 1881, sericulture in Connecticut had been entirely abandoned. The now much older Elder Sharp, who had valued his mulberry tree so highly, said, “Our silk was good, bright and strong, needing only patience to better understand the reeling… let us do what we can at this late day to repair our error.” Instead, silk-mills continued to import from Asia and continued to manufacture silk fabric through the mid-20th century. Today, the legacy of Connecticut’s silk industry can be seen in the white mulberry trees which have spread everywhere and are now considered an invasive species.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook