Why All of Upstate New York Grew Up Eating the Same Barbecue Chicken

The true legacy of the Cornell professor who invented the chicken nugget.

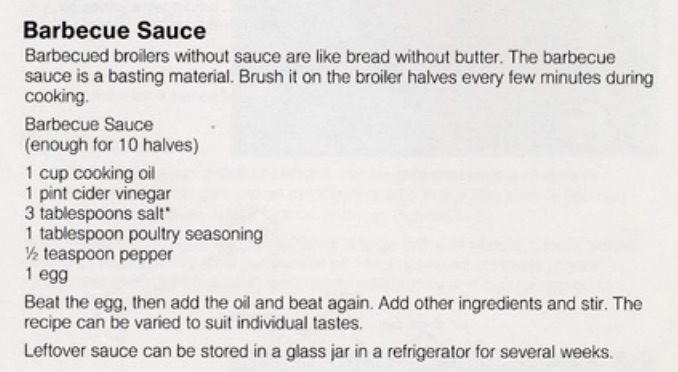

In 1950, Robert C. Baker, a professor at Cornell University, published Cornell Cooperative Extension Information Bulletin 862, which changed summer in upstate New York forever. Entitled “Barbecued Chicken and Other Meats,” the bulletin describes a simple vinegar-based sauce that can be used to turn broilers—chickens raised for their meat rather than their eggs—into juicy, delicious barbecue heaven.

At the time, this was an innovation. When Americans ate meat, they preferred beef and pork, and the poultry industry was just beginning to increase production. As an agricultural extension specialist, part of Baker’s job was to convince Americans to eat chicken. Before he passed away in 2006, he invented chicken bologna, chicken hot dogs, chicken salami, and, most famously, a prototype chicken nugget.

Cornell Chicken Barbecue Sauce, though, was his first great triumph, and what he is best known for in upstate New York. All summer, every summer, Cornell Barbecue Chicken features at backyard parties and family get-togethers. Younger generations of Finger Lake residents don’t even recognize this as a regional specialty so much as the default way to cook chicken outdoors. “Every fund-raising event, every fire department cookout, every little league barbecue, must serve this recipe or nobody would come,” writes barbecue expert Meathead Goldwyn.

Baker’s recipe is simple enough—oil, cider vinegar, poultry seasoning, salt, pepper, and egg—and delicious. Goldwyn “fell in love with this recipe in a hurry,” and Saveur called the result “one of the juiciest, most complex barbecued chickens we’ve ever tasted.” Gary Jacobson, of the Texas BBQ Posse, writes that “the sauce has been a barbecue mainstay for me” for 40 years.

The egg is a key ingredient. It helps the sauce stick to the chicken, as the albumin denatures and binds to the chicken skin, and it keeps the oil and vinegar emulsified together. The version of the recipe Cornell keeps online adds a caution about egg safety and suggests that anyone making a large batch of sauce “can use pasteurized eggs for an extra margin of safety.”

In the 1950s, this wasn’t a concern. The original bulletin notes that leftover sauce can be stored, refrigerated, for several weeks. But locals took that even further. A family friend of mine, Julie Carpenter, recalls her first encounter with the chicken, as a senior at Cornell, with a boyfriend who grew up in the area. “It was the best chicken I ever had,” she writes. When she heard about the recipe from her boyfriend’s dad, she worried about the raw egg but figured the vinegar would kill off any microbes. “I then watched him strain the used marinade, boil it, put it into a jar, add a bit more vinegar and seasoning, and put it back into the fridge,” she writes. “I almost puked. When I mentioned my concern, he said, ‘Oh no. That’s the beauty of this marinade—the vinegar kills everything.’ This didn’t stop me from eating it again in the future. And I met many other folks who did the same thing.”

The way Baker told the story, he first came up with the idea of the chicken barbecue when he worked at Penn State and the governor came to visit. When he went to Cornell a short while later, he started putting on barbecues regularly, enlisting his family and the young men who worked with him at Cornell as basters and turners.

“My father was quite a promoter,” says Dale Baker, the eldest of Baker’s six children. “He would have me and others go out in high school and cook for groups.” Roy Curtiss, who worked with Baker as a Cornell undergraduate, remembers killing and butchering chickens in the basement of Rice Hall, on campus, freezing them, and using them all summer long to create barbecues for 50 to 100 people.

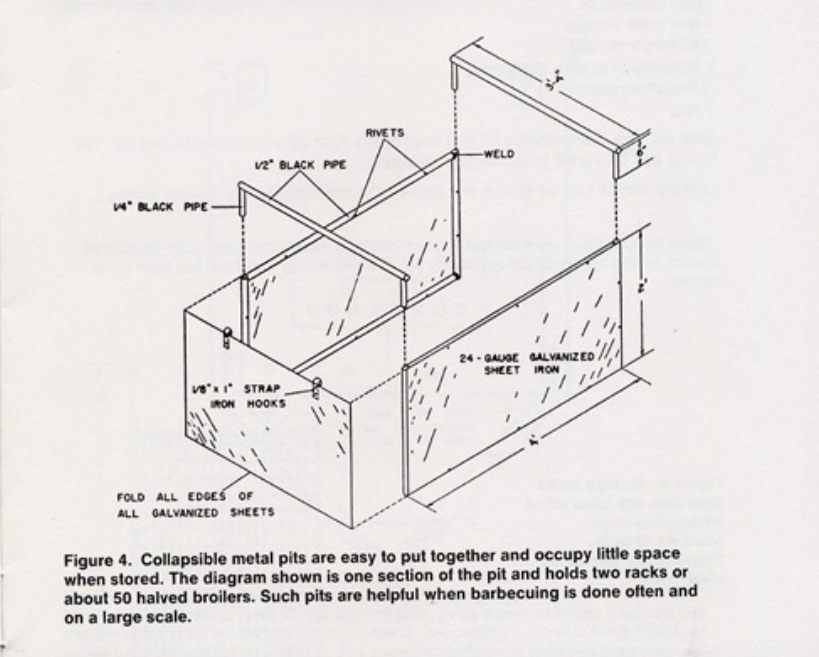

“We’d charge them a buck and half, for a roll, an ear of corn, and half a chicken,” Curtiss says. All summer, they set up for church groups and farm bureaus, toting collapsible grates in the back of a pickup truck, all around the Ithaca area. “It was very popular,” he says. “People would hear about this, and think it was a great alternative to hamburgers and hot dogs.”

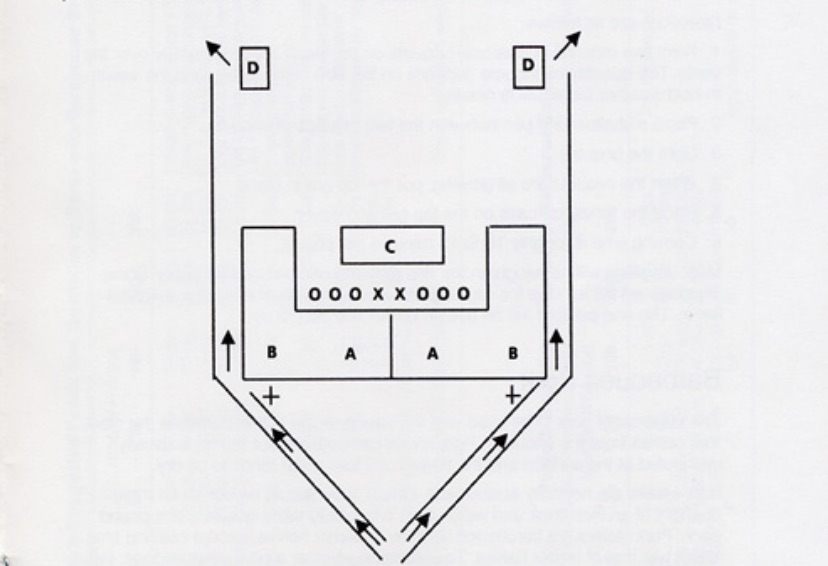

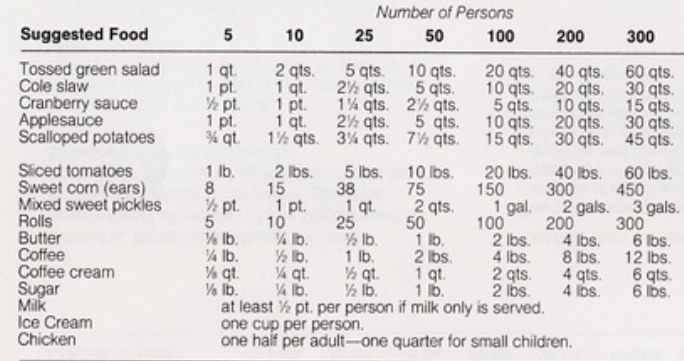

One of the key features of Baker’s published strategy was that it scaled. These big barbecues required batches of sauce held in 12-quart pans, and the helpers used wallpaper brushes to baste the chicken. “We had these arrangements—a person on either side. You had grates that you could put one on top of the other and flip them all at one time,” says Curtiss. “It was a real production. You would have people going down the line basting, and you would have guys turning, and you would repeat the process. The pits were sometimes 50, 60 feet long.” Curtiss once worked a barbecue for 5,000 people. He also helped create the chart in Bulletin 862 that shows how to scale up an entire chicken dinner, including suggested sides of coleslaw, scalloped potatoes, coffee, and ice cream from 5 to 300 people.

Perhaps the most ambitious use of the sauce, though, has been at Baker’s Chicken Coop, the barbecue stand Baker started in the 1950s at the New York State Fair. (His daughter still operates it today.) “We would cook, when I was younger, 22, 23,000 half-chickens in 10 or 11 days. It was a pretty big thing,” says Dale Baker. When he finished college, he and his dad estimated how many half-chickens they had cooked up until that point in time. It was more than a million.

Later in his career, Baker created products that were mass-produced and sold at grocery stores around the country. Cornell Chicken Barbecue Sauce never made it that big, though. “At one point in life, he put it in aerosol spray cans and tried to sell the spray cans,” says Dale. “They had to do a fair amount of research to get it so it wouldn’t clog up .... That was not a money maker.” Still, for Baker, creating the sauce and the chicken barbecue tradition of upstate New York was one of his greatest accomplishments. “I think for him this was the thing he probably took the greatest pride in,” says Dale. “It went way back to the start of his career. For whatever reason, if you asked him, I think chicken barbecue would have been top of his list.”

This story originally ran on June 9, 2017.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook