Science Finds the Cross-Continental Origins of Beer Yeast

Ales and lagers have ancestry in both Europe and Asia.

Beer is typically packaged in highly local terms. Menus tell you where their beers were brewed; breweries compete internationally for distinction; and Germany upholds its 500-year-old beer purity regulations and even has a word—“bierernst”—to characterize its national attitude toward the beverage—it means “deadly serious,” but comprises the words for “beer” and “serious.”

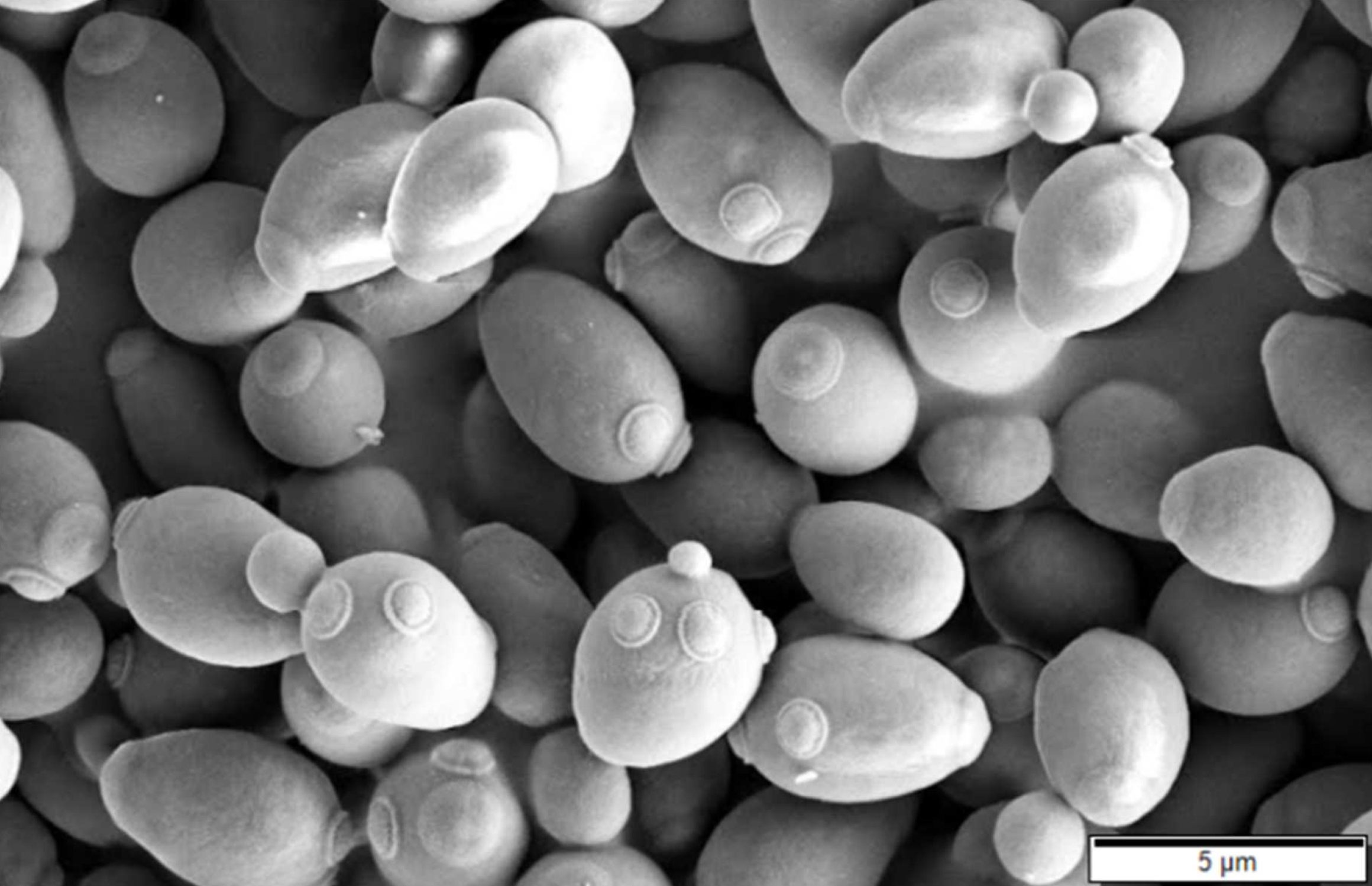

But new research, published yesterday in the journal PLOS Biology, reveals that even the smallest microbreweries might depend on genes from around the world for their beer yeast. The researchers found that Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the species of yeast that has been used to brew certain beers for thousands of years, is in fact a mixture of yeast strains found in both European grape wines and Asian rice wines. And so, they write, there would be no ales or lagers if not for the cultural exchange of fermentation technologies between Asia and Europe, possibly on the Silk Road.

Because we’ve been brewing beer since before we even discovered microbes—indeed, possibly since before we developed agriculture to domesticate cereal grains—and because we don’t exactly have a stockpile of ancient beers lying around for study, it’s been a challenge for scientists to investigate the history of S. cerevisiae. Many domesticated organisms, regardless of whether they leave traces, have complicated histories involving much movement and mixing, which can muddy up even the most agreeable samples.

Luckily for these researchers, many strains of beer yeast are polyploid, meaning that their cells contain more than two copies of their genome and, crucially, that they are reproductively isolated from their parental populations. This isolation, says the lead author Justin Fay of the University of Rochester, makes it far less likely for the strains’ origins to be “obscured by mixing and mating and things like that,” and allows researchers to take a clearer look back in time.

Fay and his colleagues gathered four beer strains currently commercially available in the United States, though Fay says that the American distributors might have acquired their strains from Europe. The researchers sequenced the genomes of these strains—two ale, one lager, and one that contained both beer and baking strains—and compared them to a panel of every publicly available yeast genome from around the world, plus those from additional strains in their lab. They found that the ale strains, baking strains, and the portions of lager strains consisting of S. cerevisiae “have ancestry that is a mixture of European grape wine strains and Asian rice wine strains and that they carry novel alleles from an extinct or uncharacterized population.” (Lager yeast, Fay explains, combines S. cerevisiae with another strain.)

So don’t be fooled the next time you encounter an “authentic” English ale or German lager—it’s actually the product of traditions spanning across continents.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook