Demystifying the Winchester Mystery House

Under new management, the labyrinthine mansion is giving up more of its closely guarded secrets.

When Walter Magnuson arrived at San Jose’s Winchester Mystery House as its new general manager in 2015, he asked the tour guides at the famed, peculiar mansion to show him everything. “I would see doors that were locked, I would see hallways that were kind of dark, and I would start asking about them,” he says. “They said, ‘You know, a lot of these spaces can only open with skeleton keys, and only one tour guide has the keys.’”

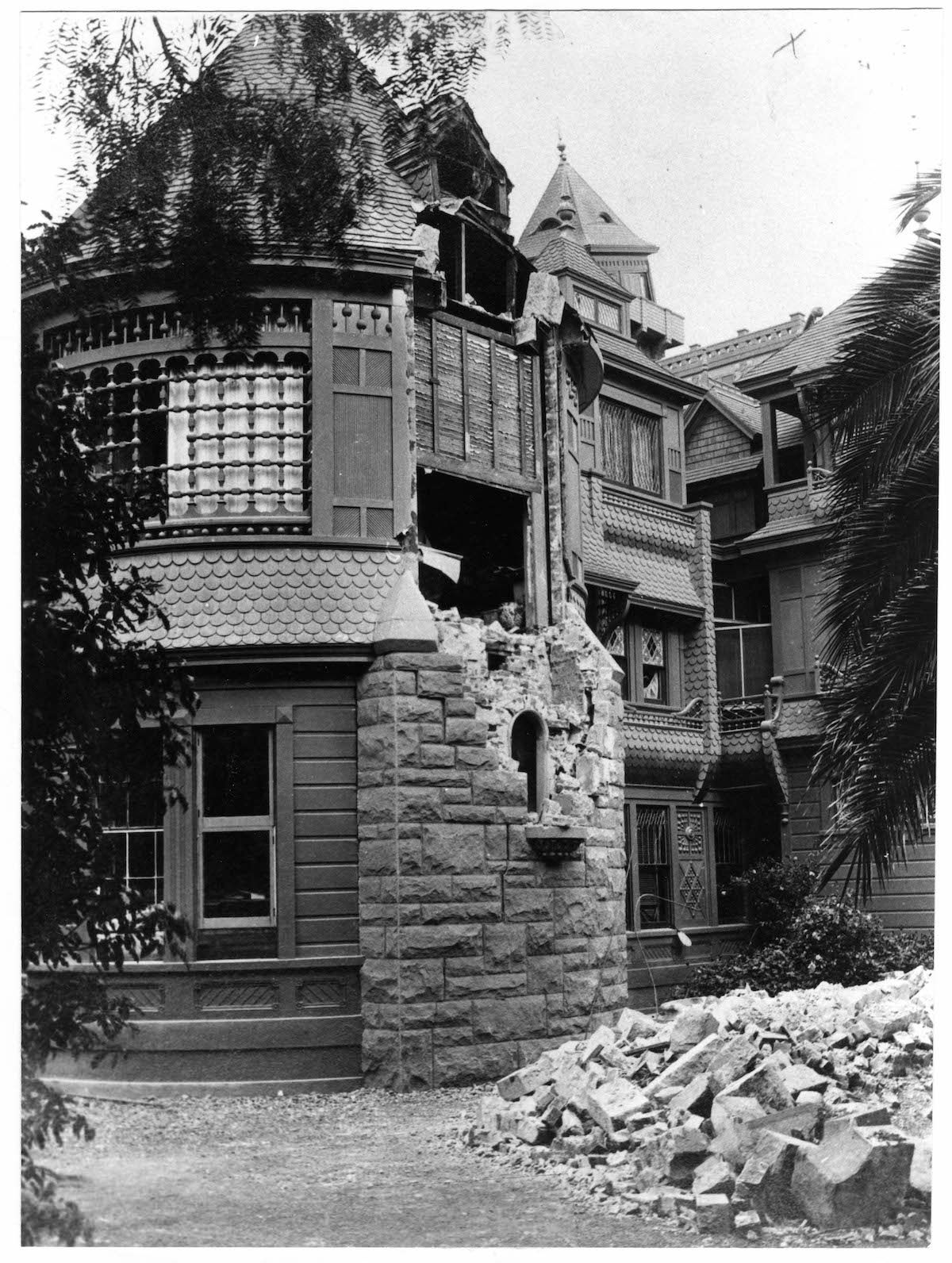

He did eventually gain access to these hidden spaces, and what he found was both astounding and in keeping with the home’s reputation for eccentricity. Some rooms were missing floorboards, others had been closed off after sustaining severe damage in the 1906 earthquake, and still more were just full of broken tiles. There were entrancing finds, too. He saw jewel-like wallpaper that scattered sunlight into tiny orbs, rows of stained-glass windows mounted inexplicably at waist height, and secret balconies that offered a bird’s-eye view of the many-gabled roof. “It was just in a constant state of becoming,” says Magnuson, who came to Winchester from a senior position at Disneyland. “Some of these spaces, you have a lot of questions: What was this room’s purpose? Who stayed here? What was Sarah thinking?”

Magnuson wanted to open some of these rooms to the public, but not all of the house’s long-term employees agreed. “Some of them were very protective,” he says. “Some of them really enjoy the spaces being something only employees know about.” Magnuson’s vision won out, as he made the decision to restore the front wing of the house to its Victorian-style, albeit sometimes unfinished, glory, and then share it with visitors.

One of the first things you notice upon approaching the Winchester Mystery House is that the front door is not aligned with the roof peak above it—it is staggered slightly to the right. This might be a minor detail, but it hints at the disorder that unfolds within. The mastermind behind this architectural oddity—a sprawling Queen Anne Revival with 160 rooms—was Sarah Winchester, the widow of the rifle magnate William Winchester. Famously private and eccentric, she built onto her California home on and off for more than 30 years. Legend has it that she did it to appease or confuse the ghosts of people killed by Winchester rifles. Getting to know the house is, in a strange way, like getting to know the woman who built it—and no ghost stories are necessary to marvel at its creativity and ambition.

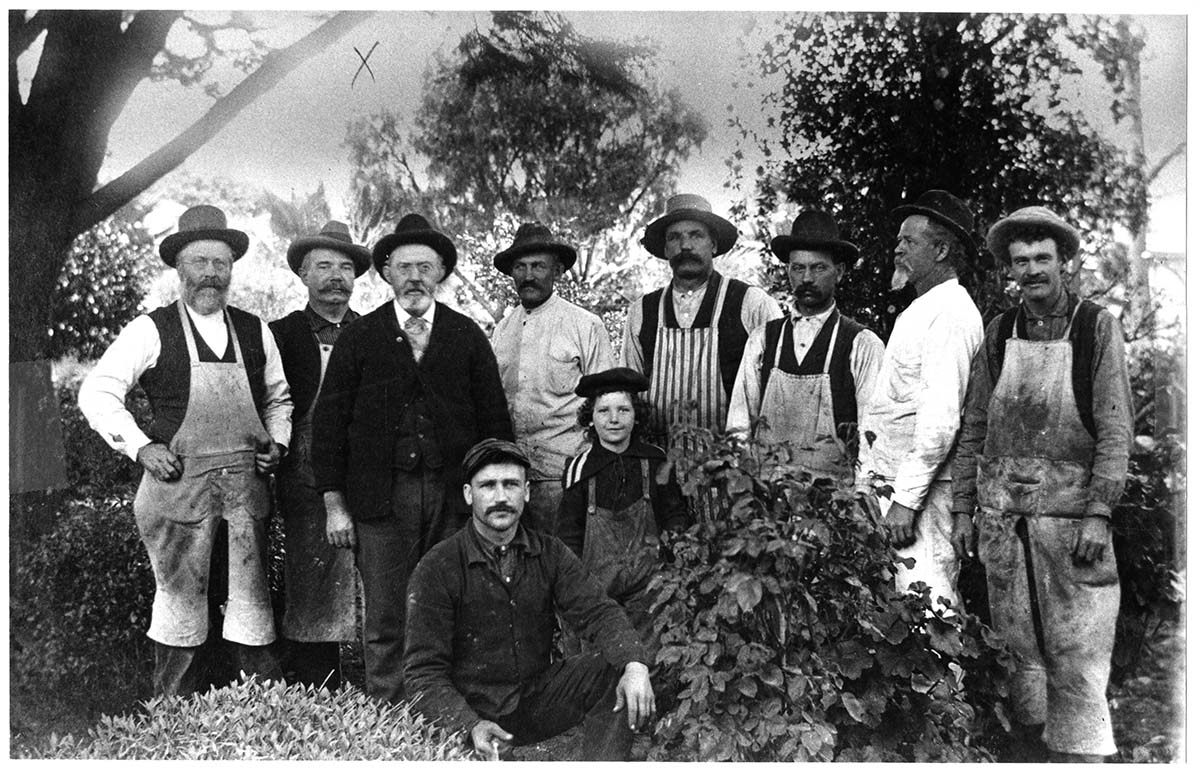

Winchester inherited $20 million after her husband died in 1881, and not long afterward moved from New Haven, Connecticut, to an eight-room farmhouse in orchard-studded Santa Clara Valley. She got to work almost immediately. A dedicated crew of carpenters built new rooms so quickly that no one bothered to draw up blueprints. And she didn’t hesitate to make unorthodox building decisions—a stairway ascending to a wall, a closet about an inch deep, a “door to nowhere” that opens to empty space. After she died in 1922, the businessman John Brown rented the house, christened it a tourist attraction, and later purchased it outright. It has been a beloved piece of quirky, creepy Americana since it opened. More than 12 million slack-jawed visitors have followed a planned route through Winchester’s singular vision.

Other than household staff, few saw the home’s interior during Winchester’s lifetime. She kept to herself following the deaths of her husband and infant daughter, Annie, from illness. For the most part, no one was permitted even to photograph her. “There’s a story about Teddy Roosevelt making an appearance in San Jose and wanting an audience with the Winchester widow,” says Magnuson. “He knocked on the front door and was not even let in.” Her eccentricity and the ghost stories—not to mention the scandal of a woman living autonomous and alone—have always been amplified in the house’s history. More striking, though, is the extraordinary artistic freedom she exercised in creating it, as well as the lengths to which today’s staff must go to keep the house intact and open.

For decades, guests have followed more or less the same path, a guided tour that takes them through a hundred-plus rooms. It starts in the courtyard, passes through a carriage entrance hall and into spaces such as the wood-paneled Venetian Dining Room and the Grand Ballroom, where Winchester installed stained-glass windows featuring cryptic quotes from Shakespeare: “Wide unclasp the tables of their thoughts” and “These same thoughts people this little world” (from Troilus and Cressida and Richard II, respectively).

Magnuson’s thought was to mix this up with new spaces to attract new and returning visitors. His restoration plan began in August 2016. After ten intense months, 40 hidden spaces—including some even the staff had only rarely seen—opened to the public in May 2017.

Some heroic construction work went into making sure the new spaces were safe, according to Michael Taffe, head of the house’s operations and maintenance team. “There’s a lot of modifications to actually make that a route,” he says. “You had raw redwood that wasn’t finished; it had to be framed and covered with plaster.” Wonky nails were pounded flat, old earthquake debris was cleared out, and floorboards installed.

One particular attic space took the most effort, says the longtime house historian Janan Boehme, who helped with the restoration plans. “That essentially was just a platform with holes in it. There were staircases and things, but there was no railing, there was no safety at all,” she says. “If you walked across, you’d just fall through a hole.” The maintenance team had to build a new wooden walkway through the space.

All of this work was necessary, in part, because after the earthquake, Winchester had almost entirely abandoned the front wing of the house. “She just kind of stopped building in these areas, didn’t finish them up,” Taffe says. “But you can tell little remnants of what the rooms looked like before the quake.” Those clues—a glazed tile here, a stretch of wallpaper there—have helped the restoration effort. One newly spiffed-up space, the dining room, is kitted out with period furnishings and textured, fondant-like wallpaper that was popular among well-off Victorians. There was some residual damage to the wallpaper from the earthquake, so craftspeople had to take molds of the surviving paper so they could recreate it. (The dining room is not part of the new tour, but is available for special events.)

By design, the restoration left some intriguing rough edges. Near the home’s front door—now in use again—is a room with bare-board walls and a shallow butler’s pantry at the back, like a book squeezed into the end of a shelf. “She often would carve little spaces out of what existed,” Boehme explains. An empty hearth also gapes not far from the entryway. After the quake, Winchester had mantles and fronts torn off fireplaces and their brick chimneys encased in metal, probably so they wouldn’t crumble in the event of another disaster.

The front hall staircase leads to a Tiffany-style stained-glass window that surely once provided bright beams of color. But it was later completely enclosed by a new exterior wall, presumably put up at Winchester’s request. Today, some strings of tiny lights illuminate it from behind.

The darkened window, however, is an anomaly. Though the house has a reputation as a dim warren, its estimated 10,000 panes of glass reflect Winchester’s desire for natural light. At one point, an outdoor patio was enclosed, so she had a skylight installed in its floor to pull light from above into the newly shrouded room below. It’s as though she carved tunnels through the house to let light penetrate.

The staircase landing opens onto an array of finished and unfinished rooms, including the Crystal Bedroom, where pale yellow, mica-flecked wallpaper gives the walls a luminous quality. One reason this room had been off-limits for so many years is concern about what sunlight might do to the wallpaper, so at some point it may need to be sealed off again.

Near there is an old photograph of the house that purports to show a milky-white ghost in the front window. On the topic of ghosts, the staff is somewhat vague, but eager to relay the experiences of others. “You definitely have folks who are very into the paranormal. They have heard a lot of stories about this place and want to experience it,” Magnuson says. “They may feel something tap their shoulder, things like that. One of Sarah’s workers named Clyde apparently still works here, and some guests see him from time to time with a wheelbarrow.”

Taffe agrees that there’s an undercurrent of something undefinable. “You don’t feel alone in the house.”

“But it’s friendly, at least,” Boehme interjects.

“Yeah, I’ve never been terrified,” Taffe says.

There’s a way that these reports of hauntings, the mythos behind Winchester herself, and the staff’s enthusiasm for it all create an atmosphere of suggestibility. The new Winchester movie plays on that idea, and so do some of the newer upgrades that have been made to the house. Taffe, who used to work at a theme park, has a nose for this kind of theatricality. He and his team recently perfected a high-octane sound clip that replicates the 1906 earthquake that brought down the house’s turreted tower and trapped Winchester in the scroll-covered Daisy Bedroom for hours. “Here it comes,” Boehme announces. “This is the full-length one.” As a speaker in the nearby bedroom emits a rising bellow, the floor starts to shake. Sounds of smashing glass and crockery punctuate the rumbles. Instability is an ongoing presence.

In the Daisy Bedroom—which is on the original tour—Winchester rang a bell to summon her servants, who couldn’t find her in the chaos. To this day, the cracked walls and torn wallpaper from that night remain, as do the panels of stained-glass flowers that give the room its name. “How would you feel if, all of a sudden, you got knocked out of bed by an earthquake?” Boehme says. “You think the world is coming down around your ears.” After she was finally rescued, Winchester left the house and stayed on a houseboat in San Francisco Bay for a while. Perhaps the boat’s steadier rocking helped quell her fears.

The remnants of the seven-story tower that toppled during the 1906 earthquake—finials, rails, and decorative trimmings that rained down like beads from a chandelier—are kept in the cavernous attic space. To make it accessible to visitors, Taffe’s team has fitted the area with myriad handholds and stabilizing planks. Eventually, the path leads up to the Witch’s Cap in the South Turret, billed as the highlight of the new tour. To reach it you must pass through a corridor scaled for a child’s playhouse, narrow and scarcely five feet high. There’s light flowing in from occasional windows, but even so, it’s hard to orient yourself in space as the walls close in.

The Cap is an unfinished round room constructed with redwood beams. When you stand precisely in the middle of the turret, your voice bounces uncannily off the walls. Boehme says that a visiting psychic described it as a great place for a seance, and reportedly that’s what drew Harry Houdini to the house in 1924—but he was less interested in communing with the dead than with proving that the entire practice was bunk. No one knows what happened, but Houdini found the visit memorable enough that he sent a newspaper clipping about it to the house’s owner.

There are hints that Winchester did have an interest in the supernatural—the house’s stained-glass spiderwebs and its repeated tributes to the number 13 (windows with 13 panes, ceilings with 13 panels, and staircases with 13 steps) don’t seem like accidents. Such beliefs wouldn’t have been particularly unusual at the time. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, there was a surge of what was called spiritualism all over the country. “The Civil War fed it,” Boehme says. “All these women, they lost their husbands, their sons, their brothers, their fathers. And they were sad and desperate for a way to see that they were okay.” Winchester herself was dealing with the loss of her whole family.

But the house’s central legend—about it being haunted by the ghosts of people killed with rifles—doesn’t come from Winchester so much as from the house’s early promoters, as well as a 1967 book called Prominent American Ghosts by a psychic named Susy Smith. Boehme finds that the legend has little power to explain Winchester’s unusual construction ideas. “Guns were looked at differently in those days. They were a necessity of life,” she says. “A lot of stories were told about her way before she died, even. She really wouldn’t engage or talk to the press because they said such bad things about her.” During her lifetime, her silence likely fed all sorts of rumors.

Boehme sees Winchester’s perpetual unmaking and remaking of the home as more of a larger-than-life artistic endeavor than an attempt to escape spirits. Local historian Mary Jo Ignoffo concurs. “This concept of gun guilt emerged out of progressive social ideals prevalent at the turn of the twentieth century,” she writes in Captive of the Labyrinth, the first full biography of Winchester. “It is highly unlikely that Sarah Winchester felt responsible or guilty for the manufacture of firearms that killed people.”

As the house’s promoters and Hollywood well know, though, darkness and tragedy—a real-life Lady Macbeth, toiling to erase the stain of blood—sells. It has also helped preserve the house. “Without those tales, I don’t think the house would be here,” Taffe says. “She would have been, you know, another wealthy landlord at that time, and the house would have been torn down.”

But those stories do, in some way, conceal the real Sarah Winchester. Publicity-shy though she may have been, she was more anchored in the real world than the spirit one. The consensus among the house’s staff is that she was a creative do-gooder who endured through profound personal loss. “She would give to causes that were dear to her, and she’d usually do it anonymously,” Boehme says. She paid her workers far more than the standard wage, and kept them on for many years in part because she wanted to ensure their livelihoods. Ignoffo speculates that she threw herself into her all-consuming building project to feel closer to her late husband—architecture had long been one of William Winchester’s passions.

Is the house a magnum opus or the product of a troubled mind? It can be both, without contradiction. And the craftsmen who spent decades laying ornate parquet floors for her eyes alone—orators addressing an empty hall—now have a larger audience than they could have dreamed of. “A lot of the focus is on some of her more eccentric qualities, or some of the mysteries surrounding her,” Magnuson says. “I think it’s important to see just how brilliant a lady she was.”

As you walk away from the house’s manicured grounds, the polished facade of the upscale mall across the street smacks you in the face. And you begin to realize that there’s a comfort to the house’s curling, hidden spaces, a freedom in its eccentricities, a majesty in its abstractions. There’s a thrill, too, in knowing that Winchester likely hid some spaces so well that no one has seen them for over a hundred years. “There’s very possibly things we haven’t discovered yet, just because we don’t have blueprints,” Magnuson says. There’s solace in the idea that, even in privacy-phobic Silicon Valley, there are still secrets at the house—and plenty of questions that don’t really even need answers.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook