Found: A Fossilized Fish in a Monastery Flagstone

A 10-year-old boy on a tour spotted the fossil and reported it to a local museum.

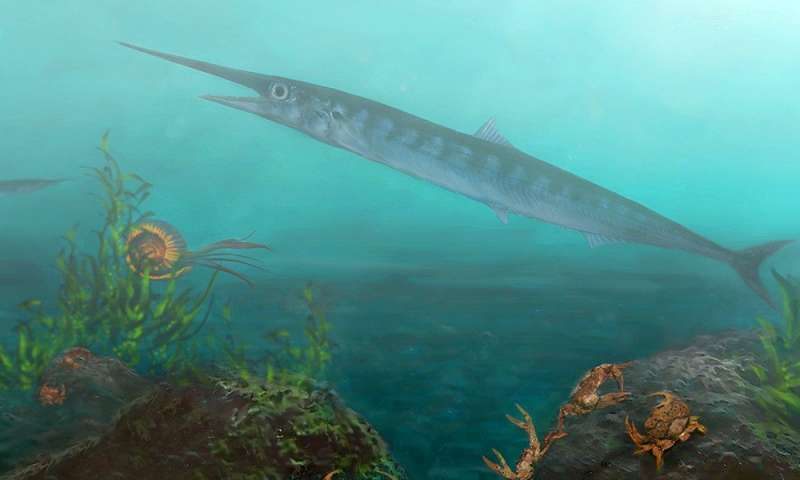

Candelarhynchus padillai was a slim, long-jawed, deepwater fish that looked a little like a modern barracuda, or at least it did, when it plied the oceans 90 million years ago. Scientists didn’t have any idea that it even existed until recently, when a 10-year-old boy was taking a tour of the 17th-century monastery of La Candelaria in Colombia. He noticed something strange: One of the flagstones of the entry pathway, which had been laid 15 years before, held fish shape.

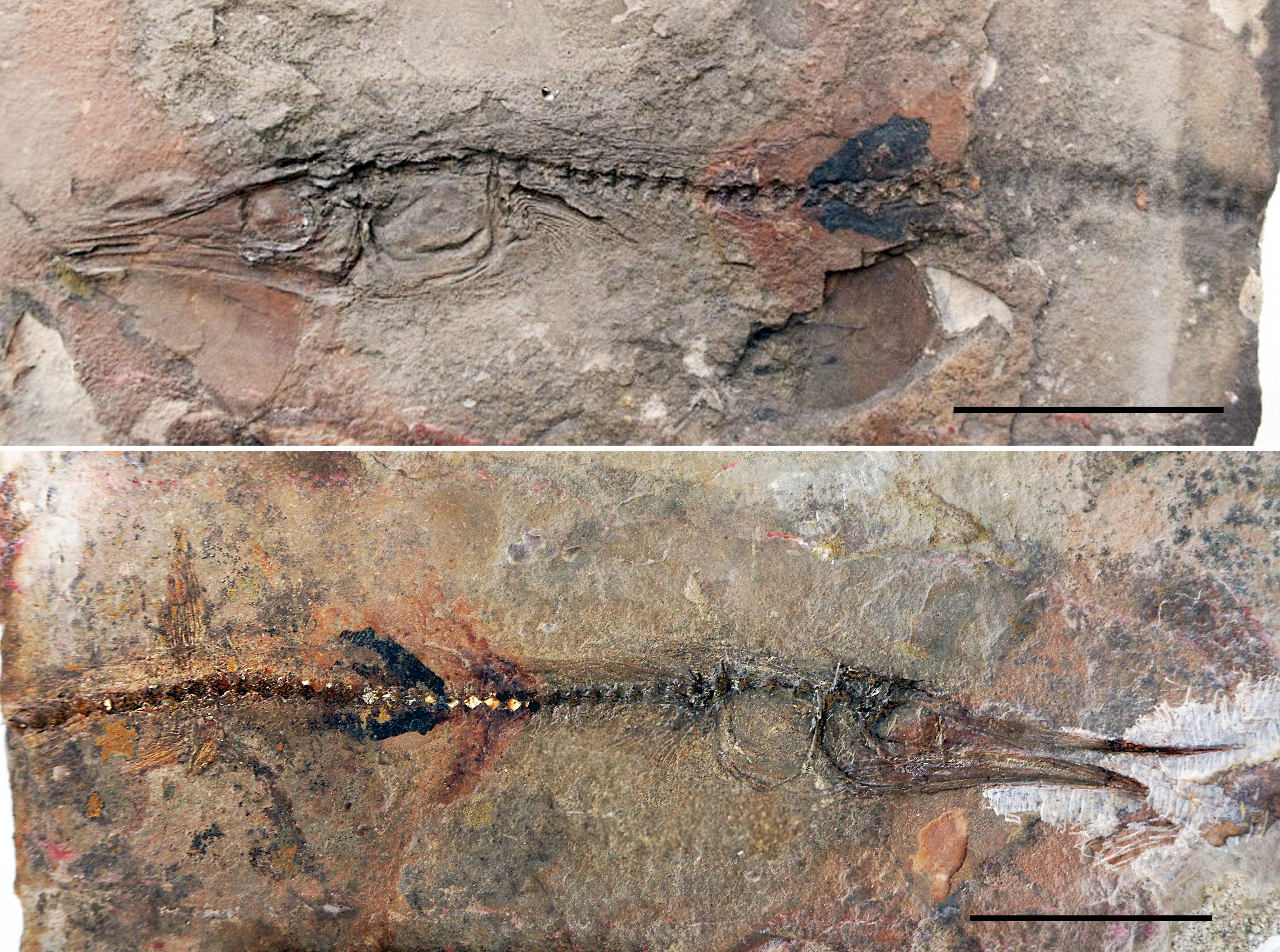

He took a photo of his find and later shared it with experts from the Centro de Investigaciones Paleontologicas, a local museum, which then pulled in its research partners at the University of Alberta in Canada to have a look at the 16-inch fossil. A team of biologists lead by Oksana Vernygora, a doctoral student at the University of Alberta, identified it as a new species, and the first fish of its family from the Cretaceous period ever found in tropical South America. They also found the other side of the fossil (the bones on one side, an impression on another) on flagstone 25 feet away.

“It’s rare to find such a complete fossil of a fish from this moment in the Cretaceous period. Deepwater fish are difficult to recover, as well as those from environments with fast-flowing waters,” Vernygora said in a statement. “But what surprises me the most is that, after 15 years of being on a walkway, it was still intact. It’s amazing.”

It is generally rare for fossils to be found on manmade structures, and it usually happens in regions that are rich in fossils to begin with. And they’re often hard to detect without knowing what you are looking for. Researchers now hope to learn more about this fish, and how marine life adapts to shifting environments.

“We can see how fish have changed as their environments have changed throughout history,” said Vernygora, who published a study on the fossil in Journal of Systematic Palaeontology with her supervisor Alison Murray and her fellow doctoral student Javier Luque. “Studying fish diversity gives us amazing predicting power for the future—especially as we start to see the effects of climate change.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook