Digging Through the Archives of Scarfolk, the Internet’s Creepiest Fake Town

Haunted TV shows, surveillance owls, liver-based children’s toys—nothing is too weird for Scarfolk.

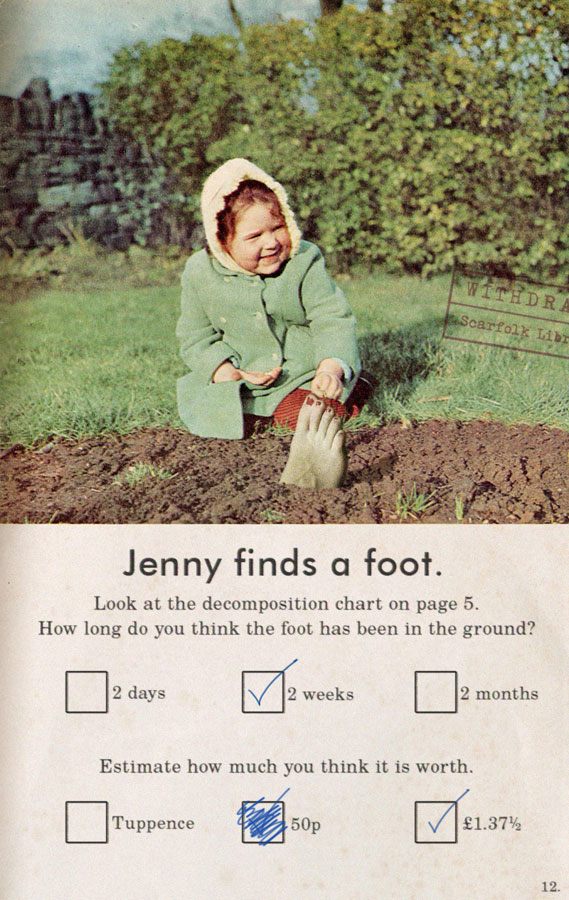

Let’s take a moment to explain the picture above. In 1978, the town of Scarfolk, in northwest England, cut its police budget in half. This drastic measure was followed by a wave of violent crime. To deal with the influx of dead bodies, the remaining police did the obvious thing—they teamed up with the “Keep Britain Tidy” campaign, and encouraged citizens, especially children, to pick up “victim debris” themselves.

If this sounds too grotesque to be true, don’t worry—it is! There were never any smiling, appendage-finding kids in Scarfolk, because Scarfolk never existed. But the town’s online presence is meticulously detailed and impressively creepy. For three years, graphic designer Richard Littler has been using his design skills and bone-dry wit to write a whole history of Scarfolk, a fictional, supernatural-tinged town that finds humor in dystopia, and is closer to today’s world than we might like to think.

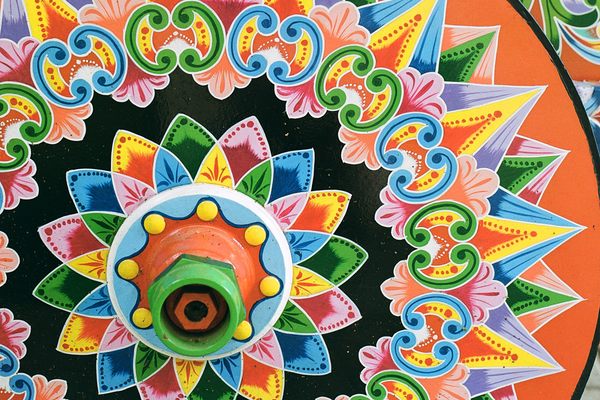

Scarfolk is perpetually stuck in the 1970s, and repeats the decade on loop. On his blog, “Scarfolk Council,” Littler presents the town’s story through materials from the council’s “archive”: posters, pamphlets and packaging that reveal aspects of everyday life. Carefully Photoshopped and inspired by real source material, Littler’s creations pack a punch—with their pastel, large fonted bombast, they could easily be mistaken for actual ’70s artifacts.

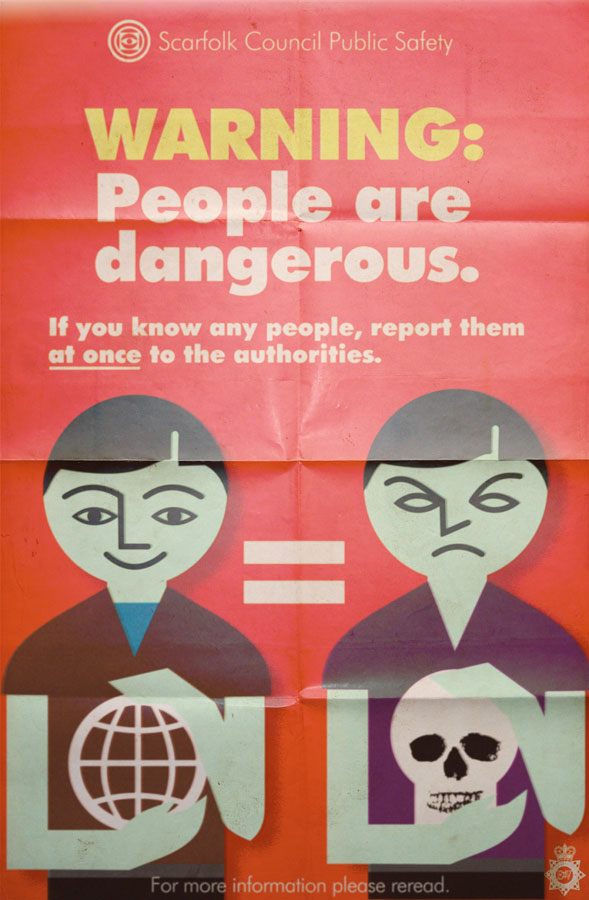

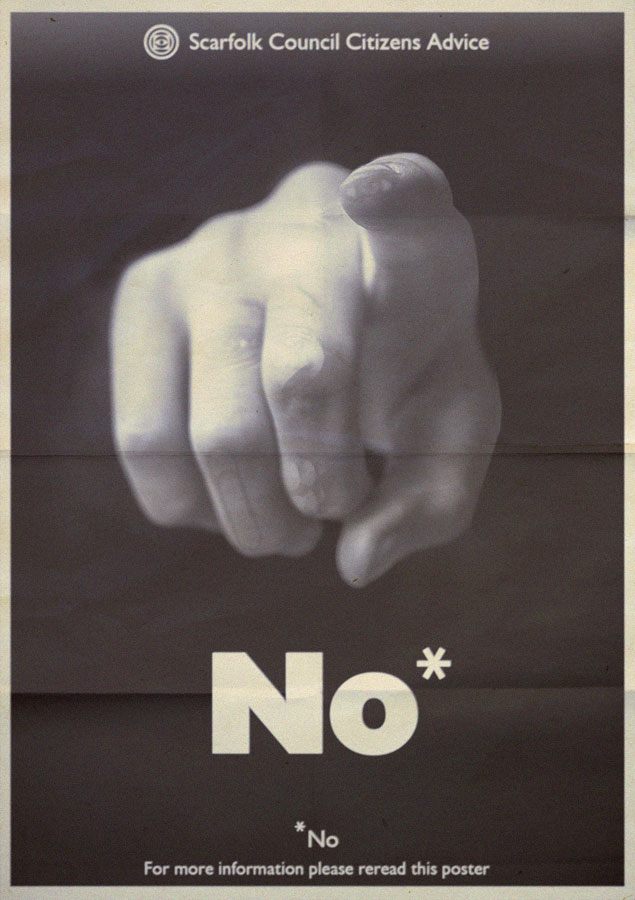

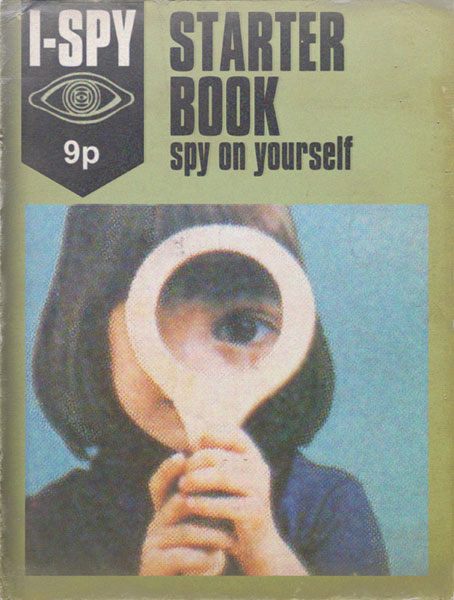

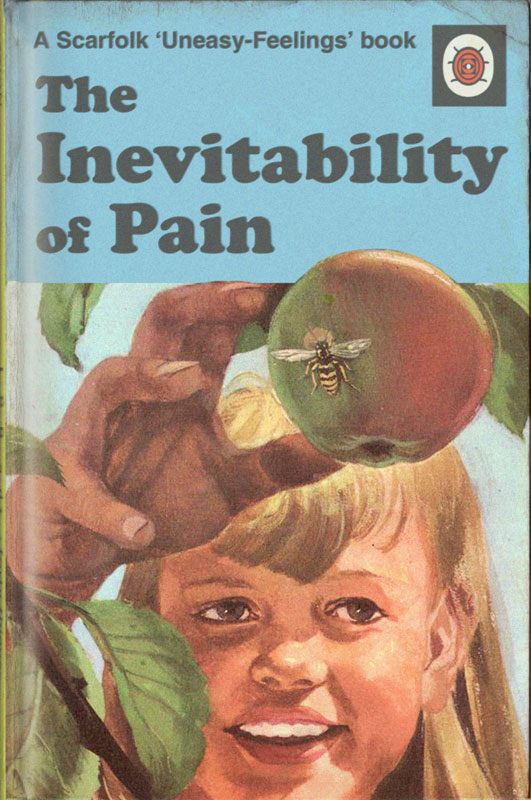

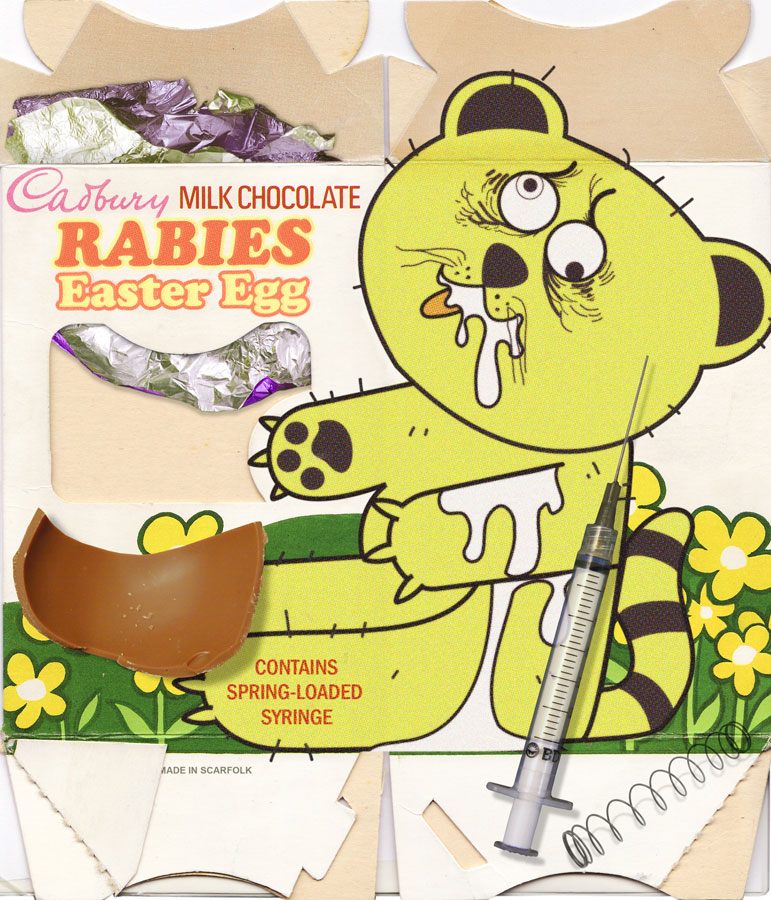

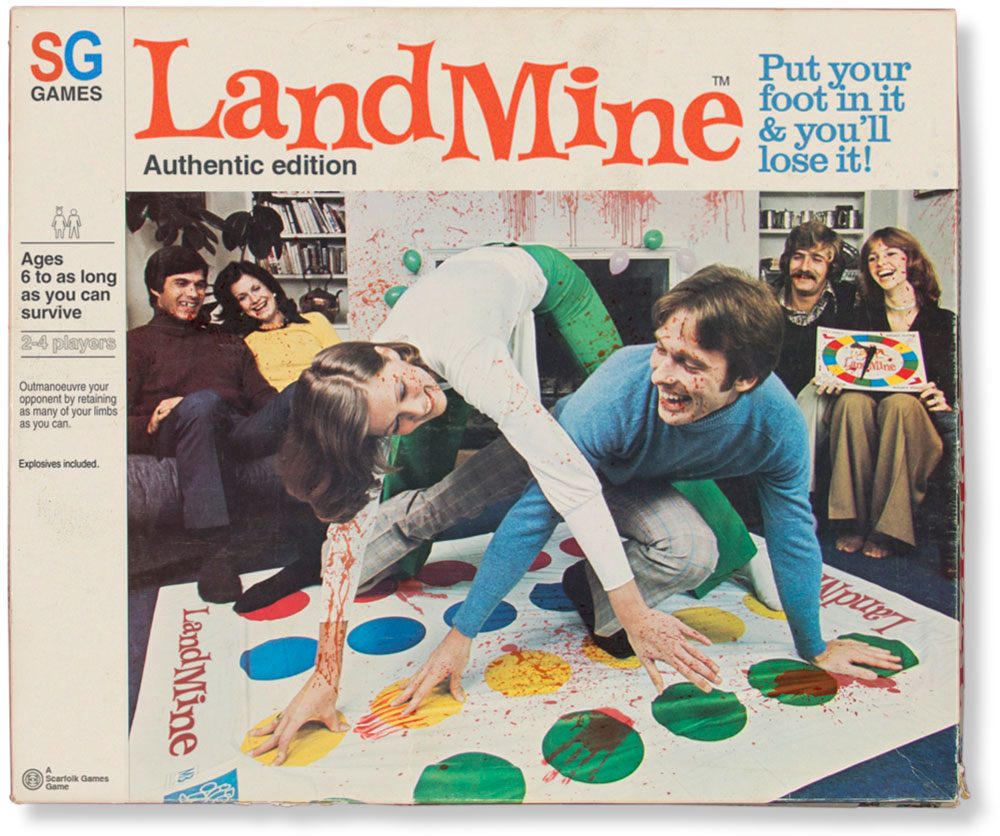

But look closely, and each has a macabre twist. A public service leaflet warns that “People are dangerous,” and instructs “if you know any people, report them at once to the authorities.” A toy called “Mr. Liver Head” is exactly what it sounds like. A Scarfolk “Pelican Science Book” looks just like the real thing—but instead of physics or chemistry, teaches you “How to Wash a Child’s Brain.”

Scarfolk’s creative creepiness didn’t come out of nowhere. Littler grew up in the 1970s, in suburban Manchester, where he remembers being “always scared, always frightened of what I was faced with.” Everywhere he turned, he recalls, was more evidence that the world was terrifying. Flip on the TV, and you might be treated to a popular public service announcement, in which children playing on train tracks are run over, one by one. Open a newspaper, and you’d be informed about botched surgeries and vengeful ghosts.

“Paranormal subjects were treated as fact by the media,” he says. “There were unsettling reports of violent poltergeist haunts in suburban homes… as a child, there seemed to be—to me at least—scant difference between the natural and the supernatural.”

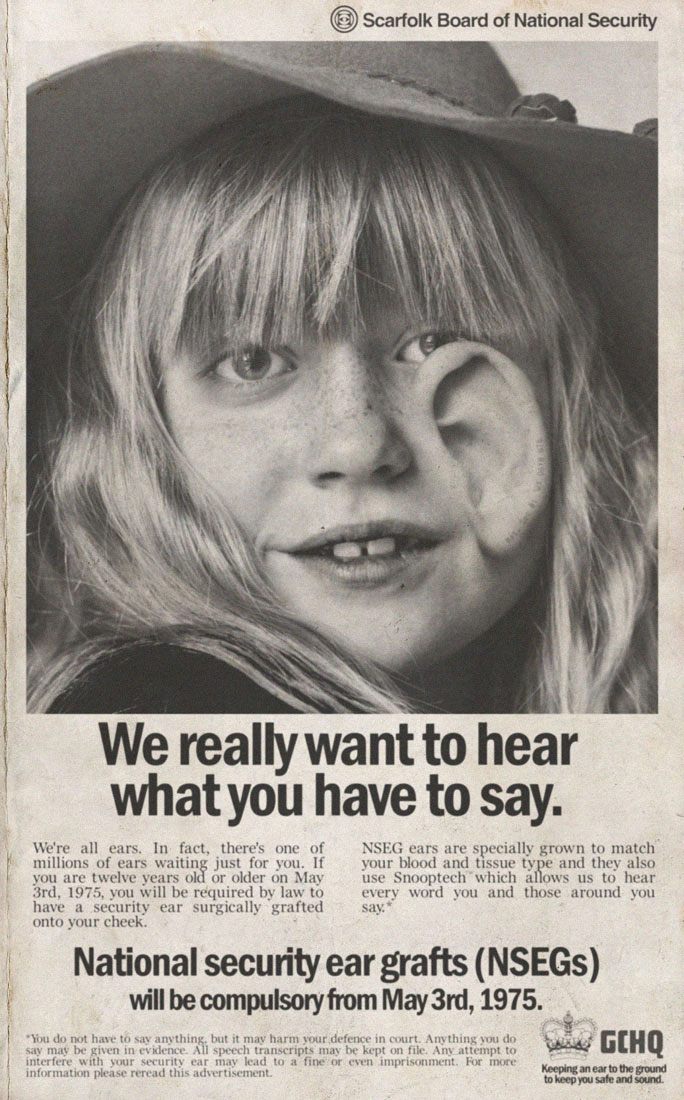

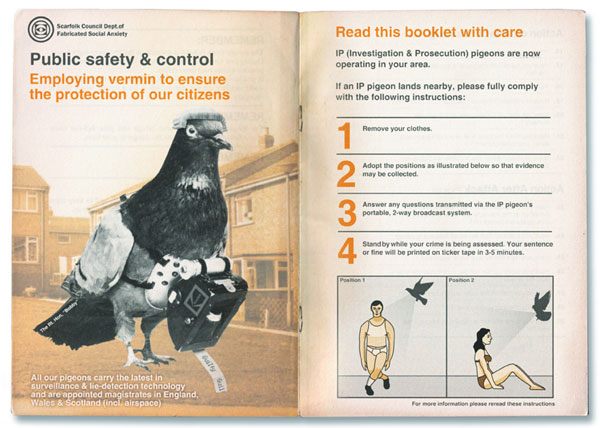

In Scarfolk, the line between reality and sci-fi is erased. National security initiatives include thought-detector vans, dream recording, and “specially crossbred, telekinetic child-owls,” which perch in people’s homes and screech at misbehaving families. An entity named “Charlie Barn,” which has a baby’s head and spider legs, hypnotizes toddlers through television programs. Doctors surgically implant music boxes into the chests of riled up children, which pop out when they are about to misbehave.

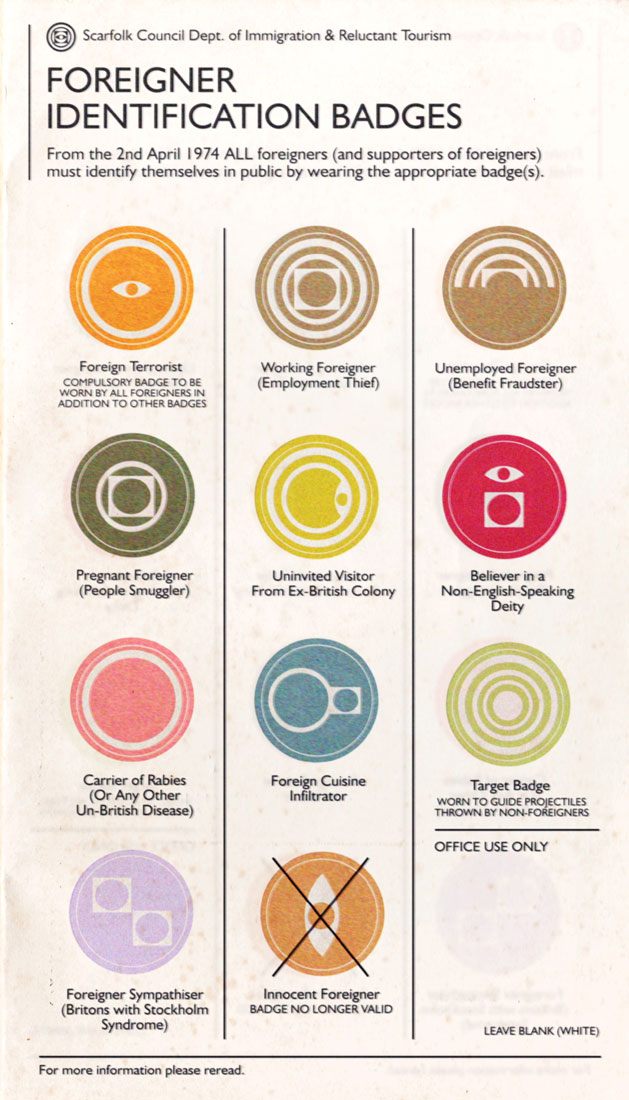

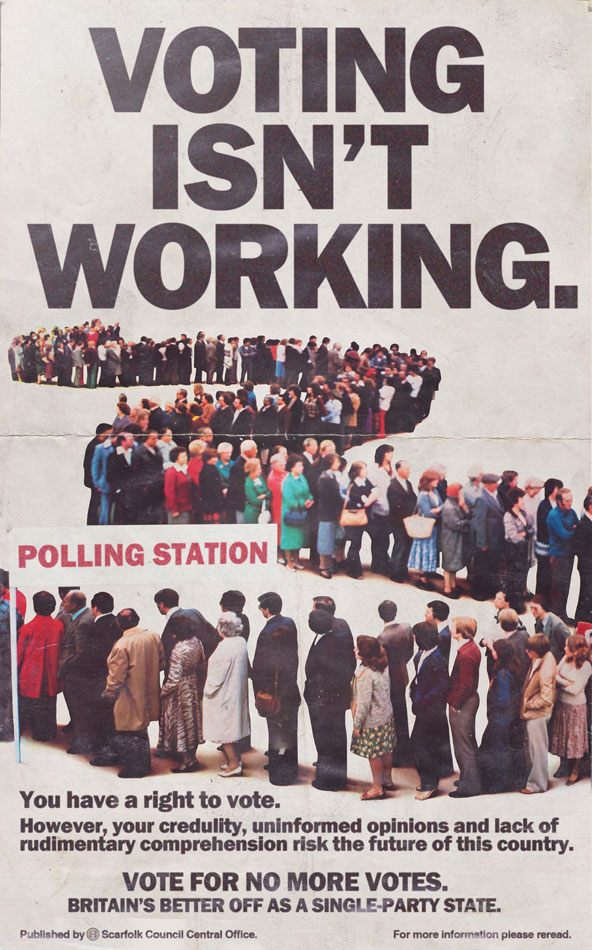

Not everything is quite so unbelievable, though. Recently unearthed Scarfolk posters and initiatives seem strikingly applicable to current events. Last week, Littler put up a set of “Foreigner Identification Badges,” which require all immigrants to publicly identify themselves as “Foreign Cuisine Infiltrators” or “Believers in Non-English-Speaking Deities”—clear satire of a certain strain of anti-immigration rhetoric.

The Council once set up a “Human Rights Lottery,” which required citizens to each “win the right to be acknowledged as a human being.” Another time, they outlawed facts, “due to their infrequency of use and diminished practicality.”

“It had not been my intention at the outset to toy with the boundary between the 1970s and present day,” says Littler. “I thought it might be interesting to mirror/juxtapose modern day events using ephemera of the 1970s—a decade the values of which we are supposed to have transcended.”

But over the past year or so, “world events and politics have slid away from the suggestively dystopian towards the blatantly and unashamedly dystopian,” he says. Sometimes people mistake his satire for real material, which he loves. ”Not a day goes by without some political event or figure rivaling the absurdity of anything a satirist can create.”

Now the Scarfolk universe is expanding—Littler has written a book, Discovering Scarfolk, and he’s working on a television show. His fans add their own magic, too. Beneath a post about the Horned Deceiver—a large, shaggy beast with a pentagram attached to his forehead—commenters join in on the world-building fun, adding characters and “recalling” strange happenings. The final comment on the post about the Horned Deceiver comes from a reader who would rather look the other way: “I’ve a pretty clear recollection that this never happened at all.”

Perhaps it didn’t—or maybe he’s just adhering to the party line. After all, the thought-detector vans could drive by at any moment.

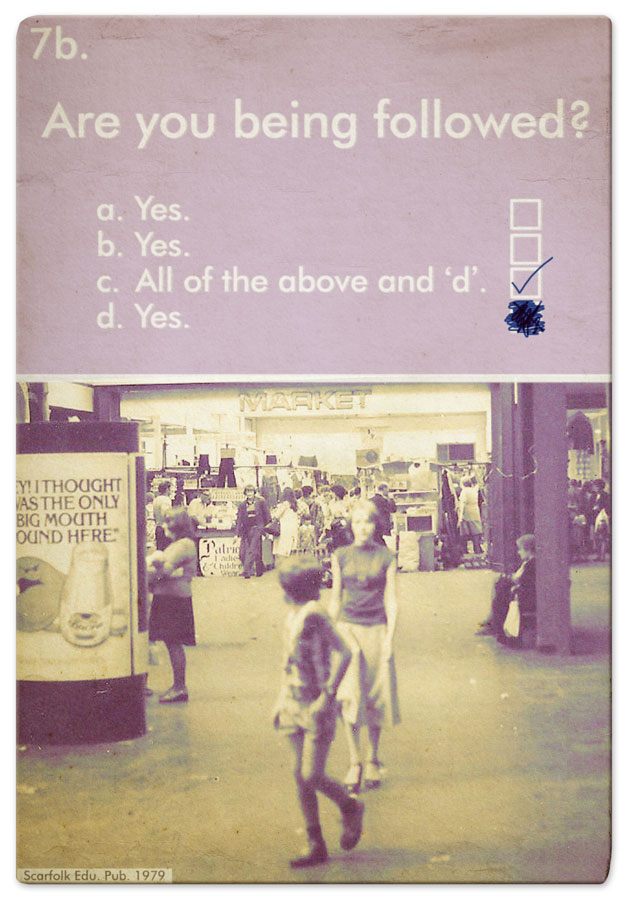

Below are some of our favorite items from the Scarfolk Council archives:

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook