Philadelphia Will Finally Memorialize an Enslaved Woman Freed in 1776

Dinah is a local legend for saving Stenton House—but she should be remembered for much more.

The unmarked grave of Dinah, a formerly enslaved Philadelphian who has become a local legend in the two centuries since her death, could be under any of the six grassy acres that make up Philadelphia’s Stenton Park. Her remains could be under the playground, picnic tables, or line of trees surrounding Stenton, a colonial-era mansion that belonged to James Logan. “We know she was buried somewhere on the grounds,” says Kaelyn Barr, director of education at the Stenton House Museum & Gardens. “We are not sure where.”

There is little doubt about James Logan’s place in history: He immigrated from Ireland in 1699, served as secretary to Pennsylvania founder William Penn, befriended Benjamin Franklin, assembled one of the finest libraries in the colonies, and negotiated with the Lenni-Lenape Nation. But we know barely anything about Dinah. She was one of several enslaved African Americans who lived and worked at Stenton in the 18th century, and is said to have saved the mansion from British forces in 1777. Now she is about to get her own permanent monument—one that is over a century in the making.

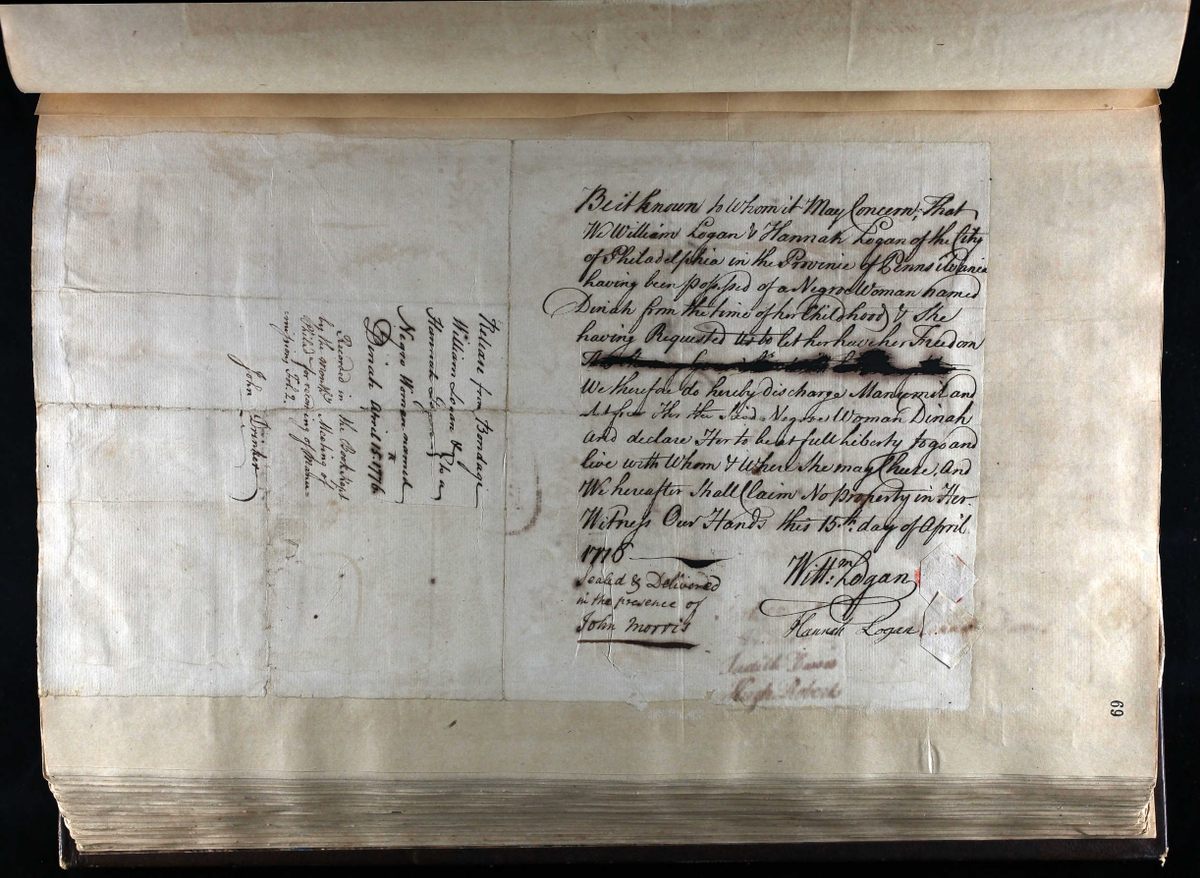

Dinah’s year and place of birth were never recorded, but according to a manumission document kept at Haverford College Library, she was enslaved as a child by the Emlen family of Philadelphia. She was brought to Stenton as part of a dowry when Hannah Emlen married James Logan’s son, William, according to his last will and testament. Dinah’s grandson, Cyrus, was also a part of the dowry, but the Emlens separated the family by keeping Dinah’s husband. (Their daughter, Bess, was already free.)

Dinah was eventually reunited with her husband at Stenton. At some point, she learned that the Emlens had sold him, and she asked the Logans to buy him. In 1757, they did, according to the Philadelphia Monthly Meeting Records. For another two decades, she was enslaved at Stenton, until she was freed on April 15, 1776. This was just months before the Declaration of Independence was signed a few miles away, and a year before British soldiers tried to burn Stenton.

In 1777, during the Revolutionary War, Dinah apparently worked at Stenton as a paid servant. In the winter, British troops torched 17 stately houses between Philadelphia and what was then its suburb, Germantown, in retaliation for American attacks at the Battle of Germantown. As a high-profile residence, Stenton was among the homes targeted.

The story goes that when two British soldiers came to set the house ablaze, Dinah was there alone. (George Logan, grandson of James, was in Europe studying medicine.) The soldiers told her their plan and headed to the barn, to find straw to use as kindling. Then a British officer rode up to the house, looking for deserters.

According to a diary kept by Deborah Norris Logan, George’s wife, Dinah cleverly directed him to the two British soldiers, who were promptly arrested. Dinah was credited with saving Stenton and its vast collection of manuscripts, which eventually became the Library Company of Philadelphia. Her story was repeated in Philadelphian history books in 1844; at first she appeared as an unnamed servant, but by 1897, her name was mentioned.

Finally, in 1910, Albanus Logan and the local Colonial Dames Society memorialized the event on a bronze plaque. It marked Dinah’s likely burial place, under an old pine tree southeast of the house. The language of the plaque was laudatory but outdated: “In memory of DINAH the Faithful Colored Caretaker of Stenton who by her quick thought and presence of mind saved the mansion from being burned by British Soldiers in the winter of 1777.”

Eventually, the plaque was transferred to the Stenton House Museum to protect it from vandalism, and Philadelphia Parks & Recreation repurposed its granite base into a water fountain for the nearby playground. Four remaining drill holes were the only clue to its past function. Recently, a multimillion-dollar renovation of Stenton Park removed the stone marker entirely.

Dinah is usually remembered for defending Stenton from destruction by the British. “This is hard, because while she is honored in the community for her bravery, we also want to honor her for the person that she was,” explains Barr, the Stenton education director. “Not just because she is said to have saved the house, where, mind you, she was enslaved for a time in her life. It’s messy and complicated, and we are really hoping to do her entire story justice.”

In the absence of a physical marker, Dinah’s story may seem like a folktale—but soon, a sculptural project initiated by the museum will carve out a space dedicated to Dinah. The neighborhood is largely African-American, and museum staff asked the surrounding community what they wanted to see in the memorial. With its input, they selected Germantown-based artist Karyn Olivier, who will install a monument within the year. Its unveiling is tentatively scheduled for September 25. (Stenton House is closed indefinitely due to the COVID-19 pandemic, but the monument will sit on public grounds.)

In a city with 1,500 public sculptures, this memorial will be one of very few dedicated to an historical African-American figure. Philadelphia’s first such monument was “A Quest for Parity,” a 2017 bronze statue of 19th-century civil rights activist Octavius V. Catto, sculpted by Branley Cadet and located outside City Hall. Last year, a sculpture of an African-American girl playing basketball was unveiled at historic Smith Playground.

Olivier will create a place where viewers can remember Dinah, but also consider how little we know about her. When the artist researched her, she found only a few relevant documents. “There were some writings in historic archives with reference to her, and they speak of her with care,” Olivier says. “But it was amazing to me that there were so many unknowns.”

The monument will serve as a contemplative space connecting the historic mansion with the public park, with two engraved limestone markers and benches surrounding a small fountain. One plaque will list questions for the viewer to ask Dinah, such as: Where were you born? How did you get here? What was your greatest sorrow? How did freedom feel? The other plaque will ask questions of the visitor.

At a community meeting sponsored by Stenton House Museum & Gardens, a neighbor proposed another question for Dinah’s plaque: Did you ever wish you had let it burn? “That’s kind of a provocative statement, because the only thing we talk about is how she saved Stenton,” Olivier says, seeming to search for the right words. “But in that servitude, were there moments when—yes, it was your home—but in that repression of who you can be—maybe there’s moments for her, moments of ‘I could be free of this.’”

The barn where British soldiers gathered straw, and that Dinah famously rescued along with the house, no longer stands. Yet her name and story survived the centuries. The outlines of her life are vague, but they are still sharper than those of other enslaved men, women, and children who lived and work at Stenton, elsewhere in Philadelphia, and across the United States.

Olivier doesn’t want Dinah’s monument to neatly wrap up this history. It will be more complex than a feel-good bronze statue of a woman whose name endured, despite her oppression. “I’m interested in monuments that confound us,” she says. “How do I get away from monuments which treat history like a period at the end of a sentence? When we all know history has to be written in pencil.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook